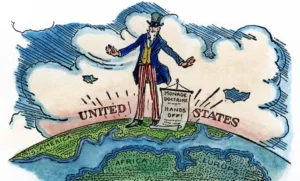

You’ve probably heard talk of the “mission creep” that has plagued recent U.S. military and diplomatic efforts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and especially Syria. But the source of American paralysis runs deeper: “purpose creep.” Even State Department officials who are candid will admit that confusion about America’s role in the post-Cold War world is pervasive. To help address purpose creep, Americans of faith should embrace a renewed sense of “prudent providentialism,” to borrow David Bentley Hart’s phrase, reclaiming America’s role as an “almost-chosen” nation.

The National Interest recently featured a series of foreign policy wonks’ responses to a worthwhile question:

Several decades after the end of the Cold War, the United States is confronting an increasingly unstable world in which its preeminence is facing new challenges. What, if anything, should be the purpose of American power?

Responses ranged widely: Graham Allison advocates a focus on nation-building at home and self-preservation. John Mearsheimer thinks the main goal should be maintaining Western dominance and preventing Chinese hegemony in Asia, not intervening in the Middle East. On the other hand, Ruth Wedgwood and Anne-Marie Slaughter want to see American power exercised in service of moral, not just material interests, championing human rights and spreading the values enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Joseph Nye believes Americans should embrace world leadership, continuing to secure international “public goods” like free trade and “monetary stability.” Robert W. Merry envisions the U.S. as Samuel Huntington’s core state of Western civilization, arguing that America “bears a burden to protect the West from any fundamental threats” in addition to securing its own vital national interests and pursuing the well-being of its citizenry. Ian Bremer, who has been thinking about this a lot, lays out a few options: “indispensable America,” “moneyball America,” and “independent America.” He leans toward independence, but mainly wants to see movement toward a clear strategy. And Henry Kissinger, the consummate realist, gave a full interview in which he mostly talks current events and reminisces about détente, but his vision of American national purpose is about building—or rebuilding—and maintaining “world order.”

Theologians were absent from the TNI lineup, and Rick Warren has yet to pen The Purpose-Driven Nation. This is odd because questions of purpose and meaning fall naturally into theologians’ purview: Who are we? For what principles do we stand? What role do we play in the drama of history? Yet despite this, and Americans’ historical affinity for theological self-understanding, even many religious believers are hesitant to reflect theologically on the question of national purpose. Some of this hesitancy is reasonable and commendable. Politicians frequently abuse religious rhetoric, and theologians justify the unjust, like the priests in Henry V who give the young king spiritual carte blanche to invade France on flimsy grounds. Historian Philip Jenkins has shown that in World War I, Christians in the participating Western nations, and Muslims in the Ottoman Empire, “found it easy to use ‘fundamental tenets of the faith as warrants to justify war and mass destruction’.” Most recently, President George W. Bush’s appeal to Providence buttressing his War on Terror rhetoric rings in our ears.

Yet for all our hesitancy, Americans need a firmer sense of purpose. Two eminent theologians, the Protestant Reinhold Niebuhr and the Catholic Richard John Neuhaus, provide examples of theologically informed but prudently tempered belief in American purpose. They each took the question of American purpose seriously without descending to jingoism, and their combined legacies constitute a warning against the extremes of cynicism and hubris. Somewhere between lies a via media of “prudent providentialism” for which we should strive. So how would they answer the question: what is the purpose of American power?

Neuhaus explicitly bemoaned the “striking scarcity of thinking about America theologically.” He emphasized that having a purpose, an important role to play in the “story of the world” according to providential design, does not mean we are intrinsically “special” in the eyes of God:

To think about the American experiment theologically, or to suggest that God is not indifferent to the American experiment, in no way implies that people who are Americans are “special” in the sense of occupying a superior place in God’s concerns and purposes. The Christian tradition gives us to understand that a beggar on the streets of Calcutta is in the view of God, sub specie aeternitatis, as important as the president of the United States…And yet, it is precisely God’s concern for everyone, including the littlest and the least, that warrants our belief that He takes an interest in realities that affect billions of people on earth. America and its role in the world is such a reality.

Neuhaus’s larger project, best expressed in his book The Naked Public Square, was to “restore the role of religion in helping to give moral definition and direction to American public life and policy.” He advocated a “critical patriotism,” possible only for a person who can affirm the following proposition:

On balance, and considering the alternatives, the influence of the United States is a force for good in the world.

He emphasized that a sense of divinely guided purpose entails responsibility, serving as a guiding North Star of the sort to which Abraham Lincoln appealed in his now-famous Second Inaugural speech, interpreting the Civil War as a possible sign of God’s judgment for “the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil,” the great stain on the national conscience. Gracy Olmstead and Joseph Loconte have appealed to this same sense of moral responsibility to address the question of Syrian refugees. For Lincoln, and by extension Neuhaus, America is “almost-chosen”—deeply flawed, but “the last best hope of earth” nonetheless.

If Neuhaus warned against cynicism, Niebuhr warned against hubris in The Irony of American History. He emphasized the irony that Americans’ newfound strength after WWII, combined with a messianic propensity, could lead to overestimation of our ability to manage the drama of history, resulting in disillusionment and inability to play our part in that history. He stressed the limits of messianic purpose, and the unpredictability of historical events; history frequently defies the hopes of its would-be managers. Niebuhr saw the limits of the Wilsonian vision of American purpose as world liberation, making the world “safe for democracy.” Bush’s attempt to democratize Iraq and the broader Middle East was a version of this progressive vision; the results suggest he ought to have tempered his foreign policy with a dose of Niebuhrian humility.

Niebuhr would likely have passed Neuhaus’s “litmus test” for a critical patriot. He asserted that, ironically for a nation with a self-image of insulation from the Old World’s woes, America in the post-war era does not have the luxury of innocence in world affairs; to disengage would be to abdicate responsibility. Though our role in the drama of history is difficult to discern, we do indeed have a legitimate role to play. Our failure to effectively deal with the continuing conflict in Syria and the broader Middle East, and what David Corey recently termed “the crisis in international religious freedom,” suggests that President Obama, said to be a Niebuhr-reader, missed this part, and perhaps ought to have balanced his reading with Neuhaus.

–

(Part II will appear tomorrow)

Ben Peterson is a graduate student at the Pepperdine School of Public Policy. He has also written for Intercollegiate Review, Public Discourse, Ethika Politika, and the New York Times. Follow him on Twitter @ben_2_long.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!