This article is Part 2 of Ben Peterson’s essay. For Part 1, click here.

We return to the unanswered question: “What, if anything, should be the purpose of American power?” What duties and responsibilities should America shoulder in the 21st century? Both Neuhaus and Niebuhr presumed a conception of American purpose that leaders such as Abraham Lincoln, John Quincy Adams, George Washington, and John Winthrop had in mind: first and foremost preserving the “American experiment.” The first duty, the first purpose of American power is spelled out in the preamble to the U.S. Constitution: “to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” Graham Allison’s version above is closest: the purpose of American power is first and foremost to defend and preserve American institutions and liberties. I suppose that also aligns with President Obama’s constant refrain of “nation-building here at home,” at least in theory.

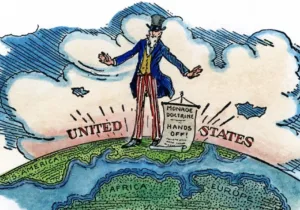

But what of our international responsibilities? What of the crumbling Pax Americana in the Middle East, the rise of China, and an aggressive Russia? Since our founding, our international orientation encouraged leadership by example as a “city on a hill,” a “beacon” to the world. This formulation, perhaps best expressed by John Quincy Adams, both clarifies and limits our aims:

Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will [America’s] heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will recommend the general cause, by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example.

By this standard, we know whom our friends and enemies should be, but we relinquish ultimate responsibility for managing history. A via media.

George Washington famously warned against permanent alliances or animosities with foreign powers in his Farewell Address. Yet he also understood times and circumstances change, and the United States could well be, “at no distant period, a great nation.” He counseled upholding commitments in which the nation was already engaged. America’s commitments, such as membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), have grown beyond that which Washington thought prudent, but his advice in favor of meeting our obligations and treating “honesty [as] the best policy” is still appropriate as we navigate the twenty-first century. We will continue to be a great nation, if not the sole superpower; we should think carefully about the commitments we make, and endeavor to keep them.

Tom Ricks, in his excellent book The Gamble on the 2007-08 “surge” in Iraq, explains that one factor in the now-squandered success of the surge was limiting the objectives. The U.S. shifted the goalposts from establishing a Jeffersonian democracy in Iraq to re-establishing security and stability for Iraqis. Today, we’re operating with inflated objectives around the world. Our default position is to embrace rhetorically almost every cause listed above by TNI’s experts—plus combating global climate change—with the result that we cannot possibly commit resources commensurate with our stated aims. We are committed to U.S. leadership and securing world order, yet our response to the Ukraine crisis is “minimalist.” We are committed to a “negotiated settlement in Syria that excludes Assad,” reflecting our appropriate default position against tyranny, yet we are not marshalling the requisite resources to achieve this end. Since there are limits to our capabilities, we must identify our key interests and responsibilities in light of a firmer sense of purpose, and then commit resources commensurate with those objectives. Otherwise, we will remain purposeless and adrift, and the burgeoning global chaos will spread.

America’s purpose as a nation is not for State Department or military officials alone to determine. The task of discerning our nation’s purpose falls to “we the people,” including the majority of Americans who believe in ultimate truths beyond power politics. Viewing the American role in the world with a sense of “prudent providentialism,” is legitimate and even essential for judging between versions of national purpose proffered by the wonks. Let the debate about America’s national purpose and role in the world begin, along with a renewed effort to see and do “the right as God gives us to see the right,” and establish “a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Ben Peterson is a graduate student at the Pepperdine School of Public Policy. He has also written for Intercollegiate Review, Public Discourse, Ethika Politika, and the New York Times. Follow him on Twitter @ben_2_long.

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy. Souda Bay, Greece (Jan. 9, 2016) Sailors aboard the guided-missile destroyer USS Ross (DDG 71) prepare to shift colors during sea and anchor detail before pulling into Souda Bay, Greece Jan. 9, 2016. Ross is conducting a routine patrol in the U.S. 6th Fleet area of operations in support of U.S. national security interests in Europe. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Justin Stumberg/Released)