Margaret Thatcher’s ghost is quite busy these days. In June Politico saw it “lurk[ing] over the Brexit campaign,” perhaps in an ongoing attempt to revive Thatcherism in England. A quick Google search for “Thatcher” and “Brexit” reveals no shortage of minds enquiring over the past few months, “Would Margaret Thatcher have been a Brexiteer?” As the Politico article proclaims, “everything in Britain seems to go back to Margaret Thatcher.”

There is undoubtedly something strange and timid about looking for leadership from a ghost.

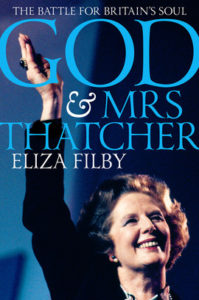

In her book God & Mrs. Thatcher, Dr. Eliza Filby, professor of British History at Kings College in London, recognizes this tendency to perceive Margaret Thatcher as some ahistorical persona present in all of Britain’s affairs. Filby thus attempts, without minimizing Britain’s first female Prime Minister’s achievements or personality (that would be a futile endeavor indeed), to “consign” the Iron Lady to her historical context. We cannot be led by the dead, no matter how formidable, but we can learn from them. In other words, when applying the thrust of Filby’s argument to the continuing post-Brexit uncertainty, asking “Would Thatcher have been a Brexiteer?” is not the operative question, but rather, “How does understanding Thatcher in her context inform us in ours?” Filby points out that the Iron Lady’s “passing simply revealed how much [Britain] had changed” between her premiership and her death. With Brexit underway, the UK promises to continue changing. After rejecting the EU bogeyman, British citizens must think deeply about what they want for their country and how they must behave to get it.

In her book God & Mrs. Thatcher, Dr. Eliza Filby, professor of British History at Kings College in London, recognizes this tendency to perceive Margaret Thatcher as some ahistorical persona present in all of Britain’s affairs. Filby thus attempts, without minimizing Britain’s first female Prime Minister’s achievements or personality (that would be a futile endeavor indeed), to “consign” the Iron Lady to her historical context. We cannot be led by the dead, no matter how formidable, but we can learn from them. In other words, when applying the thrust of Filby’s argument to the continuing post-Brexit uncertainty, asking “Would Thatcher have been a Brexiteer?” is not the operative question, but rather, “How does understanding Thatcher in her context inform us in ours?” Filby points out that the Iron Lady’s “passing simply revealed how much [Britain] had changed” between her premiership and her death. With Brexit underway, the UK promises to continue changing. After rejecting the EU bogeyman, British citizens must think deeply about what they want for their country and how they must behave to get it.

Apart from contextualizing Thatcher’s life and legacy, God & Mrs. Thatcher, as the title implies, contributes to our understanding of Margaret Thatcher by tracing the Christian, specifically Methodist, origins of her political convictions. It places what her husband, Denis Thatcher, called her “deep religious faith” at the center of the narrative. Filby recounts that Denis referenced his wife’s faith when correcting Bernard Ingham, who purported to enumerate Mrs. Thatcher’s leadership style with five characteristics, none of which touched on religion. Like Denis Thatcher in that instance, Filby contends that including Margaret Thatcher’s faith is essential for understanding the Prime Minister. She goes a bit father, however, rightly situating Christianity as the organizing theme for Margaret Thatcher’s whole life and work. Refreshingly, the author understands that ideas and beliefs can be powerful motivators, even for powerful people.

Some ideas encountered in childhood stick. To see this in Margaret Thatcher’s life, one must start in Grantham, a small town in Lincolnshire where she grew up. As a politician, Thatcher invoked her early years for overtly political purposes (to distance herself from the “millionaire’s wife” label and extol the virtues of capitalism), but her time in Grantham was truly formative. Margaret’s father was a devout Methodist and a grocer. She inherited his abhorrence of debt, so it is “not without irony” that her government later allowed significant expansion of personal credit. Both father and daughter struggled to reconcile the creative power of free-market capitalism with the materialist culture it encouraged. Filby’s text shows Thatcher’s world-view never severed itself from Grantham.

As the introduction to God & Mrs. Thatcher advertises, the book is not technically a biography. This is clearly seen in Filby’s overview of the late 1960s, a time when political discourse presaged somewhat the discussions now surrounding Brexit. 1968 was a year of upheaval. The political center was in crisis. Enoch Powell delivered his “Rivers of Blood” speech, which stirred fears about immigration in the midst of a struggling British economy. Sound familiar? Powell was vigorously anti-European but ardently pro-market, a policy pairing that has earned him the title “God-father of Thatcherism.” It should be noted, however, that in the 1970s Margaret Thatcher strongly supported the European Economic Community (EEC), which Britain entered in 1973. Similarly to modern discourse, immigration fueled in some quarters the sense that “British-ness” was eroding. By 1980 “a tangible sense of England” was entering Tory thinking on immigration and European federalism.

Thatcher became party leader in 1975 and won the PM position in 1979. Once in office she followed Powell’s belief that the Gospel is primarily for the individual and that “original sin” could be leveraged against utopian visions of society. Powell also paved the way for Thatcher’s opposition to the agenda of liberal Anglicanism, calling the clergy amateurs in economics and politics.

The juxtaposition of Thatcher’s government—its philosophy and policies—with the Church of England’s political-theology and agenda is a central theme of God & Mrs. Thatcher. Due to internal division within the Labour Party, the established Church offered the most scathing and forceful critiques of Thatcher and her government. In the first half of the 20th century, scholars like R.H. Tawney and Archbishop William Temple spearheaded an intellectual fusion of socialism and Christianity. This outlook became orthodox among Anglo-Catholics and paved the way for Thatcher’s showdowns with the Church and its leader, Robert Runcie, the Archbishop of Canterbury and a liberal theologian with a penchant for the middle road. In the 1980s the bishops in the House of Lords rarely affected legislative outcomes, but between 1979 and 1990 “only 27% of the Bishops’ votes were in support of the government.” The Archbishop of Canterbury voted against the government at a 6:1 ratio.

The Church’s most enduring responses to Thatcherism were more intellectually powerful than politically influential. Filby dwells longest on Faith in the City, a 1985 report on inner city poverty, unemployment, and “social dilapidation” led by Anglican Bishop David Sheppard and Catholic Archbishop Derek Worlock. It proved “one of the most incisive and important critiques of Thatcher’s Britain,” though it did not let the church off the hook either. Two nations existed in Britain, according to the report: struggling inner cities and comfortable suburban neighborhoods. It challenged “Thatcherite individualism and self-help” by arguing that the existence of the one nation entails the existence of the other. Recently, the Church of England released a comment on Faith in the City that confesses the report “misunderstood [Thatcher’s] motivations” at the time. A careful reading of God & Mrs. Thatcher ought to yield the same conclusion. Filby clearly shows that Thatcher’s Christian beliefs and ideas motivated her outlook and policies, although she also argues that “a high unemployment rate proved… a lasting feature of the neoliberal economy.”

Filby captures the theological aspect of these disputes between Thatcher and her “turbulent priests” in the 1980s in an anecdote from the memory of Richard Harries, Bishop of Oxford. During a meeting Thatcher interrupted Archbishop Runcie’s description of inner-city poverty with a monologue about “the harmony between Christianity and individual liberty.” This theme lies at the core of what Filby calls “the Gospel according to Margaret Thatcher,” but the Bishop of Chester interrupted the Prime Minister on this occasion: “I’m afraid you misunderstand, Prime Minister. Christianity is not about freedom. It is about love,” he observed.

If Thatcher was guilty of overly individualizing her theology, the church was guilty of overzealously pushing its politics. For example, in 1985 David Sheppard declared on national television that it was “very difficult to find thoughtful Christians on the Right.” Filby notes on several occasions that while the church often succeeded in its role as the conscience of the state, ecclesiastical policy suggestions were often either lacking or recycled. She lends some credence to Nigel Lawson’s assessment: “If only they had stuck to religion, we all would have been better off.”

God & Mrs. Thatcher reads smoothly and combines copious research with scholarly insight. History in this text is not the rise and fall of impersonal groundswells, but the interaction and succession of influential persons; their voices, crusades, debates, and contests of will comprise the bulk of the narrative. One enjoyable aspect of the read is tracking the myriad of conflicting opinions and viewpoints, often strikingly articulated, about the same sets of circumstances. Thatcher’s dispute with Runcie over how to interpret Britain’s Falkland Islands victory is only the most prominent example.

The book’s key insight, that the central questions in post-war Britain through Thatcher’s premiership sat at the intersection of theology and politics, is a rejoinder to those who think the church-state dialectic has counted for little in the modern world. This dialectic was contained within Thatcher herself. Filby offers a convincing portrait of a devout, principled leader who was also a pragmatic politician.

The concluding analysis falls somewhat flat, nevertheless, in its closing evaluation of the Iron Lady’s political philosophy. At certain points the final chapter flirts with accepting the contention of the liberal bishops and scholars in Thatcher’s day, namely that it is difficult to be a classical-liberal and a Christian. While never directly suggesting that support for financial or retail markets is un-Christian, Filby harps on the fact that Thatcher—by plugging personal profit and not regulating big banks—and the Church of England—by investing in malls and supermarkets—fostered consumerism inimical to Christianity. Preaching “moral capitalism” unintentionally begot a system that rewarded knavish speculators and promoted reckless behavior.

Thatcher once said of her aims in office, “Economics is the method; the object is to change the soul.” To her credit, Filby shows this to be a futile endeavor. Markets do not change the soul; they reflect human frailties. They can profit by glorifying idolatry and often tempt unto ruin consumers who cannot reign in their desires. Yet, they can also provide opportunities to the down-and-out and reward those who provide needed goods and services to their fellows. The Christian socialist critiques amount to more than FYIs only if we assume, as Thatcher mistakenly did, that markets are supposed to make men morally good. One can criticize Thatcher on this point, without defaulting to Christian socialism.

Filby, though, chooses to endorse a sentence from William Temple: “The art of government is to so order life that self-interest prompts what justice demands.” The line sounds delightful, but this governmental ordering of life smacks of overbearing limits on reasonable freedoms. More fundamentally, this critique also forgets, in its own way, what it accuses Thatcher of forgetting: the Fall. In the Genesis account, the desire to be like God, the orchestrator of life, is the original sin. Those in power are the most vulnerable to this seduction. God set up conditions conducive to His children’s flourishing. But He allowed for outside influences and let Adam and Eve order and act on their desires so that, learning the consequences, they might come to know themselves and their creator’s love. Margaret Thatcher seems to have internalized this reading of the Fall, despite aspiring to “change the soul.” It is a model philosophy of government.

Of course, it was not perfect. Filby shows that—in the face of globalization—Thatcher chose not to respond to job losses in the declining British industrial sector, but placed great faith in the generous and industrious spirit of the British people. The years after the Brexit referendum—widely understood as a reaction against globalism—may themselves be a referendum on this Thatcherite view. How much do nationalist Brits need their neighbor nations to the south—their people, goods, ideas, and markets? English voters ousted what they saw as an overbearing foreign bureaucracy, and economic analysis of Brexit suggests unilateral liberalization could hedge against any consequent loss of access to the common market. If disenchanted Brits are able to swallow that, take responsibility for their circumstances, and demand accountability from their representatives, they would have lived up to Margaret Thatcher’s expectations. If the government can maintain but manage globalization with an eye toward the low-skill workers and inner city neighborhoods, they would have learned from a Thatcherite oversight.

—

Will Higgins is an Intern at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He studies Political Science and Classics at Samford University.

Photo Credit: Lady Margaret Thatcher exits a limousine on the ramp at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland in June 2004 to attend Ronald Reagan’s funeral. By U.S. Department of Defense.