Last week Galen Carrey, vice president of government relations for the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), made a plea in Christianity Today for Americans to support President Obama’s U.N. nuclear testing ban. Like the Catholic Church, many Protestant Christian churches have adopted the thinking of the secular left when it comes to American nuclear weapons. The argument goes like this: nuclear war would be catastrophic and would cause the death and suffering of countless people; therefore, the United States should limit its nuclear weapons in a variety of ways: either by limiting the type of warheads and delivery systems, shrinking the quantity of weapons, declaring a smaller scope of purpose they serve (perhaps to deter but certainly never to “use”), or even abolishing the weapons altogether.

Before discussing the merits of maintaining the option to test U.S. nuclear weapons, we must first examine the purpose of government, and whether or not nuclear weapons are inherently and categorically immoral. Scripture shows that God’s purpose for government is to commend what is good and punish what is evil. In other words, it is to seek justice and, thereby, protect the innocent. God has given government the prerogative to use lethal force in its path of obedience (Romans 13:3-4). Christian just war theory remains the guide for how Christians have traditionally thought about how and when the government can wield the sword in the way God intended. Just war theory allows for the use of force as long as it meets the criteria for justly entering into war (jus ad bellum) and the criteria for justly waging the war (jus in bello).

Nuclear weapons possess no moral agency; rather, the regime leaders who possess them or seek them do. So, like other kinds of weapons developed and employed by nations, nuclear weapons can be employed justly and for just ends, or they can be employed unjustly and for evil ends. North Korea, a regime that tragically and cruelly oppresses its people and shows no regard for the inherent dignity of human beings, uses nuclear weapons to coerce and blackmail other regimes like South Korea and the United States in order to dissuade them from exacting punishments on Pyongyang for its violations of UNSCRs and overt acts of war. It threatens to employ nuclear weapons against American civilians (it does not possess the ability to successfully limit its attack to one against military forces) in response to the U.S. military conducting military exercises with its ally, South Korea. North Korea uses nuclear weapons for unjust causes. There is no moral equivalence between the way North Korea uses nuclear weapons and the way the United States uses nuclear weapons.

The purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons is, and ought to remain, to deter catastrophic war and preserve relative peace and stability. Ultimately, they protect innocents. Nuclear weapons have served as the bedrock of U.S. deterrence since the nuclear attacks that brought WWII to a close. In a compelling essay, Admiral Mies, former Commander of Strategic Command, showed in a single chart a percentage of wartime fatalities relative to world population. It remained high—around the 2% range from 1600 all the way to WWII when it jumped to above 2.5%. It then precipitously dropped to below half of a percent, which is where it remains today. A weighty burden of proof—not a priori reasoning unsupported by facts—for the merits of returning to the days before nuclear weapons existed rests upon those who wish to return to them. (With one important distinction, because nuclear weapons have been invented, even achieving a ban would in reality merely move us to the increasingly precarious situation in which current nuclear powers move to latent nuclear powers.)

Paradoxically, the more credible the threat of a U.S. nuclear response to extreme threats, the more enemies or potential enemies will be deterred. Or, as Admiral Mies explained, “they deter conflict by the possibility of their use, and the more a potential adversary perceives the credibility of our capabilities and will, the less likely they are to challenge their use.” It matters less what the United States deems necessary to deter and more what other nations are actually deterred by. While “extreme threats” are not clearly defined, one can deduce that they may include threats to overthrow allied regimes, threats to kill mass numbers of civilians in an allied nation, threats to the survivability of U.S. alliances, and certainly military threats to the U.S. homeland or U.S. forces abroad. Contrary to popular thinking, the United States does not threaten to employ nuclear weapons only in response to a nuclear attack. The prevailing and current declaratory policy of the United States is one of strategic ambiguity. We don’t want to tempt enemies to attack the United States or our allies with non-nuclear weapons, believing that the attack would be worth the cost of any non-nuclear response from the United States. Media reports indicate President Obama may change current U.S. nuclear doctrine from one of strategic ambiguity to a policy of “no first use”, despite the fact that the President’s own Nuclear Posture Review Report (NPRR) eschewed doing so mere months ago.

President Obama laid out his nuclear agenda in a 2009 speech in Prague. His agenda included shrinking and further limiting the U.S. nuclear deterrent while also promising, to his great credit, to ensure it remains safe, reliable, and modern as long as other countries possess nuclear weapons. To date, he has followed through on this last commitment by supporting the Congress’s budgets to modernize the aging force and to maintain the three legs of the nuclear triad: the delivery systems that launch nuclear warheads including intercontinental ballistic missiles, bombers, and submarine launched ballistic missiles. But, in pursuit of the President’s Prague agenda, he also worked to negotiate the New START Treaty with the Russian Federation, as well as the now infamous “Iran deal”, both of which came at great strategic loss to the United States and did not lessen the prospects of nuclear war.

Now, in its last months in office, on the 20th anniversary of the signing of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, September 24th, the Obama administration will submit a United Nations Security Council Resolution that “would call for an end to nuclear testing”. The only way to ban U.S. testing is to circumvent the U.S. Senate, which remains opposed to the ban. In 1999 the Senate voted against ratifying the CTBT for good reason. First, and most obviously, the United States may one day determine that it must resume testing in order to maintain the safety and reliability of the nuclear deterrent. The United States has refrained from testing since President George H.W. Bush’s self-imposed ban in 1992. So far, this has not caused a significant drop in the confidence of the weapons’ performance. But, as new weapons designs are adapted to meet modern challenges, it is possible that testing may one day be required. Second, other countries do not abide by treaties like the United States does, and the problem is confounded when the treaty does not define what constitutes an actual nuclear test. According to Russian nuclear expert Dr. Mark Schneider, “Reports of low-yield hydronuclear tests have appeared in the Russian press since the 1990s” and members of the bipartisan 2009 U.S. Strategic Commission report stated, “Apparently Russia and possibly China are conducting low-yield tests.”

Galen Carrey, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), and whoever else advocates for a weaker U.S. nuclear deterrent, such as through a U.N. resolution that would prohibit nuclear testing and hamstring the United States, are misguided. The United States must pursue policies that ensure the U.S. nuclear deterrent is safe, reliable, and credible. Enemies must believe the United States may one day employ nuclear weapons in the pursuit of justice, for the protection of innocents, and for peace. Reserving the right to resume nuclear testing is one such means to maintain such a credible deterrent.

—

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs is a fellow at Hudson Institute where she provides research and commentary on a variety of international security issues and specializes in deterrence and counter-proliferation. She is also the vice-chairman of the John Hay Initiative’s Counter-proliferation Working Group and the original manager of the House of Representatives Bi-partisan Missile Defense Caucus.

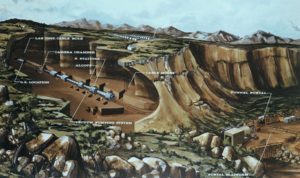

Photo Credit: Test Chamber from the Diamond Sculls underground nuclear test, which involved a 21kt explosion on July 20, 1972 at the Nevada Test Site (now known as the Nevada National Security Site). From 1951 to 1992, 928 announced tests were conducted at this Department of Energy facility. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!