For the first time in the history of the United States, we failed to condemn an anti-Israel resolution at the United Nations.

On December 23, 2016, our government abstained, rather than opposed (as all previous presidential administrations have done), an anti-Israel resolution (UN Resolution 2334) that condemned its West Bank settlements (even in East Jerusalem, where expansions to long-existing Jewish communities have not been criticized by past Palestinian leaders) as illegal.

Then yesterday, John Kerry defended our abstention as the only way to keep the two-state plan alive. He failed to make serious mention of Palestinian terrorism, which has been the main obstacle to a two-state solution because it has revealed support for terrorism by the same Palestinian Authority that would head a putative Palestinian state. He also failed to note that Arabs attacked Jewish presence in Israel long before 1967, when the first modern settlement on the West Bank was built. West Bank settlements are not, and never have been, the root cause of Arab hostility to the Jewish state.

Americans need to understand what historians have known for decades: West Bank settlements on the whole (the exceptions are those on land that is owned by Palestinians, and the Israeli Supreme Court has condemned these) are not illegal. To say that they are illegal is an egregiously politicized misreading of history.

Let me explain why.

According to UN Resolution 242 (1967), which is the most-invoked basis for alleged illegality, Israeli withdrawal was to take place in the context of Arab-Israeli mutual recognition of the right to exist and territorial adjustments to achieve secure boundaries. Withdrawal was ordered from “territories,” not “the territories.” Both Arthur Goldberg and Lord Carrington, the primary authors of this resolution, have said that the word “the” was purposely omitted because it was not intended that Israel give back all of her territories, since they recognized that some were needed for secure boundaries.[i]

Despite the fact that most Arab states have refused to recognize Israel’s right to exist (a condition of Resolution 242), Israel has implemented the principles of the resolution three times. When Egypt terminated its claims of belligerency in 1979, Israel returned the Sinai—90 percent of its occupied territory. When Jordan signed a peace agreement, Israel returned land claimed by Jordan. Then, in September 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew from Gaza, only to be met with new attacks on her civilians launched from that territory.

The charge of illegal occupation must therefore be rejected. Israel has made repeated efforts to comply with UN stipulations for the territories, while her Arab neighbors have not.

When the Palestinians appeared to accept Israel’s right to exist during the Oslo negotiations (1993–95), Israel turned over control of major West Bank cities to the Palestinian Authority (PA). But when the PA showed support for terrorist attacks on Israeli citizens in 2000, Israel resumed control of those cities. In that same year Israel offered to return 92 percent of the West Bank, which some dismiss as ungenerous because, they claim, Israel never owned the land in the first place. Yet Jews have lived in ancient Samaria (the West Bank) for over three thousand years.

But that’s not all. I remember the moment some years ago when I first learned that Jordan unilaterally renounced all claims to this area in 1988 and released legal ownership to Israel at that time. That alone helped me realize that the claim of Israel’s illegality was less than certain.

But many anti-Zionists are either unaware of this or ignore it and suggest that Jews should remove all settlements from the West Bank, leaving it entirely for Palestinians. That would be as unreasonable as insisting that no Arabs can live in Judea or Galilee. Yet most Jews are happy to live with 2 million Arab-Israeli citizens in Judea and Galilee. Besides, what other country has been required to give up land that it won in a defensive war it did not start? Do Germans displaced from Koenigsberg agitate for that German city to be returned to them by the victorious Russians?

Resolution 2334 also claims that the settlements in the West Bank violate Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. This is ironic, because this convention was adopted to prevent crimes like the Nazi deportation of Jews to death camps. The article prohibits “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or that of any other country, occupied or not.” But no Israelis are being deported against their will—they are moving voluntarily; nor is any Palestinian Arab being deported or transferred. And legal settlements, which are on only 3 percent of the West Bank, were bought by agreement with Arabs.

The article refers to a “High Contracting Party” with a sovereign claim to territory. The West Bank is not the territory of a signatory power, but, as Eugene Rostow stated in 1990, “an unallocated part of the British Mandate.” The “green line” that determines important boundaries of the West Bank was simply the cease-fire line at the end of the 1948–49 war between Arabs and the new Jewish state. The Egyptian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement of 1949 stated that the demarcation lines were “not to be construed in any sense” as “political or territorial boundaries.” True boundaries would be made only with “the ultimate peaceful settlement of the Palestine problem.” In the intervening years, Jordan moved into the West Bank without any international approval or official recognition and then withdrew after attacking Israel in 1967 and being defeated.

It is helpful to recall that in the San Remo Treaty of 1920, the victors of the First World War created a territory called Palestine, comprising what are now called Jordan, Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. This was 1 percent of the former Ottoman Empire, 99 percent of which was transferred eventually to self-governing states with mostly Arab and Turkish populations. In 1922 the League of Nations in the Palestine Mandate stipulated “close settlement by Jews” on the land west of the Jordan River, which includes what we call the West Bank. That same year the United Kingdom created the new Arab country of Jordan, which meant that Britain gave three-fourths of the mandate to Arabs and one-fourth to Jews. The West Bank was part of that one-fourth. The mandate has never been abrogated and endures today.

Why should Americans care about what the UN did and the US failed to do regarding Resolution 2334? For several reasons.

First, justice. If you want greater justice in Israel and the disputed territories, then you will want Jews and Arabs on the ground to talk to each other and work out incremental changes—the kind of changes that have already been taken to improve everyday lives for Palestinians. But this resolution discourages these incremental changes because it teaches Palestinians to ignore their Jewish neighbors and go over their heads to international bodies and media. It teaches Palestinians they don’t have to compromise on ownership of the West Bank because the UN, with American support for the first time, has just declared that Jews have no right to any part of historic Samaria.

Second, truth. This resolution perpetuates falsehoods—that the Israeli occupation of the West Bank is illegal, and that the Israeli government has not made difficult compromises for the sake of peace.

Third, theology. This perpetuates the divorce in Christian minds between Jesus and the New Testament, on the one hand, and the present land and people of Israel, on the other. For too long, Christians have wrongly believed that God’s covenant with Jews ended with the death of Jesus and that the land of Israel no longer is significant to God. The fact of the matter is that God still loves the Jews—even non-messianic ones—and that the New Testament authors predicted a time when Jews would return to the land that would then be restored to Jewish ownership. Biblical scholars make this case in The New Christian Zionism: Fresh Perspectives on Israel and the Land .

—

Gerald McDermott is the Anglican Chair of Divinity at Beeson Divinity School. He is the author or editor of eighteen books, and the editor of The New Christian Zionism.

Notes:

[I] See also Prosper Weil, “Territorial Settlement in the Resolution of November 22, 1967,” in The Arab-Israeli Conflict, ed. John Moore (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), 321.

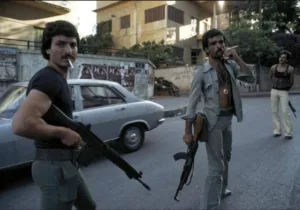

Image: East Jerusalem, credit: Mujaddara source: Wikimedia commons

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!