The most prominent international development of recent years has been the rise of a “crescent” of instability, civil war, and bloodshed in the Middle East, stretching from Lebanon in the west through Syria and Iraq to the Iranian border in the east. It has captured the world’s attention, with the danger it represents for the major oil and gas reserves on the planet, with the rise of the murderously-telegenic Islamic State (IS), and with the potential of a spiraling regional all-out Sunni-Shia sectarian whirlwind that would ingest countries from Iran to Saudi Arabia to Turkey, spewing them out in shreds.

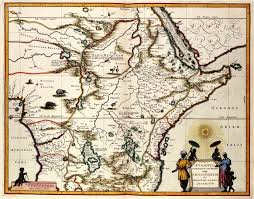

However, the focus on this northern crescent has distracted international attention from the emergence of a second, no less dangerous, crescent of faltering, failing, and failed states in the south. Encompassing now much of northeastern Africa and southern Arabia, this crescent may prove to have consequences just as dire as its northern predecessor. The only serious bulwark against the descent of the southern crescent into total chaos is the rise of Ethiopia, a Christian-majority, market-oriented, and relatively democratic regional power, which already functions as a force for stability in several neighboring countries. To continue and expand this role, Ethiopia needs and deserves the support of the United States and the West.

Failing and Failed States

The starting point for the emerging southern crescent of chaos is Libya, on the Mediterranean shore which, since the violent toppling of the Ghaddafi dictatorship in 2011, has disintegrated into a failing state today. The country is currently divided between an Islamist government in Tobruk and the east, and a more extreme Islamist government in Tripoli and the west. All the while, perched between them lies the zone ruled by the most extreme and IS-affiliated Islamist militias, governing the Wilayat (province) around Sirte in the name of “Caliph Ibrahim”—the murderous Iraqi Islamic scholar (and former inmate at the Camp Bucca US internment center in Iraq) Ibrahim al-Badri, aka Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. Released in 2004 as a “low level prisoner”, all IS-affiliated groups now regard him as the supreme ruler of Islam. Several other political and tribal factions ruling smaller areas jockey ruthlessly against each other for power and influence.

To the southeast of Libya are Sudan and South Sudan, politically separated since 2011 yet sadly united in a common slide towards failure. Sudan, after generations of strife which brought about a largely peaceful break from the non-Muslim south, had the opportunity to enter a phase of stability and recuperation. Instead, it is now tumbling into a new civil war—this time an intra-Muslim one between the Arabic-speaking east and the African-languages-speaking west (Darfur and Kordofan). Not to be outdone, newly independent Christian-majority South Sudan, without any strong institutions or traditions of self-rule, has supplied in its short history the gloomily familiar spectacle in post-colonial Africa of recurrent violence between leading tribal groups—here specifically between the Dinka and Nuer. Only a fragile political truce now prevents all-out civil war.

Hopping eastwards to the horn of Africa, where the Red Sea meets the Indian Ocean, we find Somalia, a failed state if there ever was one. Since 1991, the county has ceased to be a politically unified entity: most of its areas are contested between a feeble UN-recognized “official” government and several Islamist militias and local warlords, the most prominent being the homicidal Al-Qaeda affiliate al-Shabaab. Meanwhile, the northwest of the country has practically seceded, functioning for the last 25 years as a relatively stable and moderate, nominally independent “Somaliland”.

Just across the Red Sea from Somalia on the southernmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula is Yemen. Long a faltering state, Yemen is now the latest addition to the list of failing ones. Politically divided since the “Arab Spring” of 2011, its divisions have, within the last year or so, escalated into full-blown civil war between belligerents, each of which holds territory. An alliance of militias headed by the Shiite Ansar-Allah (aka Houthis, after their founder) and supported by Iran, presently controls the north and west of the country. The Sunni forces of the former “official” government of President Hadi, supported by Saudi Arabia, controls only portions of the country, especially in the south around the city of Aden. Meanwhile, the vast but sparsely populated east is to a great extent controlled by Al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), currently the most active of Al-Qaeda franchises and proud publisher of the Jihadi youth-magazine Inspire. Nevertheless, AQAP itself is increasingly challenged by new IS-affiliated armed groups. Recently, Saudi Arabia too has entered the fray, attempting to forestall the complete collapse of the pro-Hadi forces by conducting military strikes against the Houthis, albeit ineffectively to date.

Faltering States

After the dismal list of clearly failing or failed states comes a list of faltering ones—places less volatile, at the moment, than failed states though which display worrying signs of patent incompetence at dealing with mounting challenges and instability. Such countries need to rapidly stabilize and regain confidence in their ability to overcome current difficulties, or else risk a swift slide into the vicious circle that has destroyed so many of their neighbors.

First among these is Egypt. For generations a stable regional power and regarded as the leader of the Arab world, Egypt has been gradually undermined by decades of colossal government corruption and incompetence, resulting in a systemic economic deterioration that has brought it to the brink of bankruptcy. Egyptian insolvency is currently averted only by periodic and massive cash injections by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which nevertheless only just suffice to keep it afloat. These dire economic straits are the background to a brittle political environment; since 2011 this has resulted in two brusque regime changes, first the toppling of the  Mubarak kleptocracy, and then a military coup ousting the elected Muslim Brotherhood government of Morsi. The current Egyptian regime, led by General Sisi, is struggling with stability. With some short-term success, it faces the daunting long term prospect of dealing simultaneously with a barely solvent economy and a brittle political legitimacy, while at the same time confronting an increasingly violent Islamist opposition as well as an actual armed insurgency by IS-affiliates in the northeast of the country, which they now term “Wilayat Sinai”.

Mubarak kleptocracy, and then a military coup ousting the elected Muslim Brotherhood government of Morsi. The current Egyptian regime, led by General Sisi, is struggling with stability. With some short-term success, it faces the daunting long term prospect of dealing simultaneously with a barely solvent economy and a brittle political legitimacy, while at the same time confronting an increasingly violent Islamist opposition as well as an actual armed insurgency by IS-affiliates in the northeast of the country, which they now term “Wilayat Sinai”.

Another increasingly unstable country within the southern crescent is Eritrea, on the shores of the Red Sea. A small, Christian-majority country enjoying a relatively educated population and good infrastructure, it looked ideally poised to gain from commerce and tourism opportunities towards some degree of economic and social progress after its consensual separation from Ethiopia in 1993. However, under the erratic and brutal rule of president-for-life Isaias Afwerki, its short history is mainly a chronicle of political repression and a tottering economy, while its ruler appears to be mainly concerned with syphoning-off the largest possible sums from the his impoverished population’s depleted funds into his Swiss-bank account—at last count an estimated 695 million USD. Continuing on this course, it is surely only a matter of time before the country’s economic or political structure (or both) collapses.

The latest addition to the list of faltering states, is certainly the most surprising one—Saudi Arabia. At first glance this seems incongruous, for by some appearances the Saudis have an outwardly stable political and economic situation, possessing both the world’s second-largest reserves of hydrocarbon fuels and a state-of-the-art equipped military. However, beyond the shining veneer of wealth and stolidity, widening cracks are becoming evident, pointing to a likely crisis in the making.

Public discontent, notoriously hard to gauge in repressive societies, is rising unmistakably, and the rate of anti-government incidents is increasing. The Saudis are witnessing intensifying dissent among the sizable and downtrodden Shiite minority, perhaps a third of their total population and a regional majority in the southwest as well as in the eastern, oil-producing provinces. Meanwhile, among the regime‘s core constituency of devout Sunnis, who increasingly regard the regime as hopelessly corrupt and religiously lax, there is a growing pull of Islamist ideology, even towards militant groups like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Saudi citizens feature prominently in the list of IS activists and suicide bombers, and several recent large-scale terrorist attacks on Shia places of worship in Saudi Arabia point to the IS strategy of fanning sectarian conflict within the country. The growing fear among the Saudis is from an “Iraqi scenario”, where repeated IS-inspired attacks on Shias stir up Sunni-Shia sectarian strife to the point of explosion, whereby the government loses its ability to maintain control.

This mounting internal instability is coming at a time when the country is also experiencing patent difficulties with its military intervention in Yemen. Far from delivering the expected swift and decisive blow to the Iran-supported Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen, the Saudi military intervention there, albeit enjoying absolute air and sea superiority and employing some of the world’s most sophisticated weaponry, is struggling to overcome the rag-tag militia confronting them. Indeed, the Houthis are not only effectively resisting Saudi attacks, but even successfully delivering surprise counter-attacks within Saudi territory. Besides reflecting badly on the government’s competence, this inept military performance also risks embroiling the Saudis more deeply into the widening regional Shia-Sunni sectarian conflict, precipitating internal strife and bringing it into a direct collision course with Iran. The clear awareness of populations across the region to such a scenario is best illustrated in Iran-supported Shiite militiamen in Iraq reportedly plastering artillery shells they fired at the IS-held Sunni Arab city of Fallujah with the name of Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, the prominent Shiite Saudi cleric the Saudi regime executed in early 2016.

The failures of the Saudis’ aggressive strategy are especially significant as the government of King Salman has staked much of its credibility on this policy by prominently placing in leading roles the “two Muhammads”—Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef, as Minister of the Interior heading the battle against enemies on the internal front, and the king’s son (and second in line to the throne) Prince Muhammed bin Salman as Minister of Defense heading the military effort on the external front in Yemen. Since Salman’s accession to the throne in January 2015, the traditionally cautious, consensual (and slow) process of Saudi decision-making and acting has been replaced by a far more decisive and confrontational style, which does not shirk from ignoring and even alienating many of the royal family’s prominent princes. The results of this new approach, however, leave much to be desired. If the new policies and the operational leadership by the “two Muhammads” do not deliver evident successes soon, the kingdom risks returning to earlier practices of internal dissension and strife even within the royal family—practices which previously led to the unseating of King Saud by his brothers Muhammed and Faisal in 1964, to the ousting from the succession of Crown Prince Muhammad by his brother Faisal in 1965, and to the assassination of King Faisal by a nephew in 1975.

Ethiopia Rises

Against such a dismal regional background of increasing instability and failure, there is however at least one significant bright spot: Ethiopia. One of a handful of civilizations across the world with an uninterrupted history since antiquity, the only early Christian nation never to be conquered by Islam, and the only country in Africa never to have been successfully brought under colonial rule, Ethiopia has a unique character and story that owes much to its unusual bible-based national identity. According to Ethiopian tradition, their nation was born 3,000 years ago when Makeda Queen of Sheba returned from her visit to the wise King of Jerusalem carrying Solomon’s child and accompanied by thousands of Israelite soldiers sent to defend her. As the soldiers settled down in Sheba and married local women, a new mixed Israelite-African people were created. Headed by Menelik, the “son of the wise man” born to Makeda and Solomon, the new people went on to conquer neighboring lands and to create the Ethiopian nation, with Menelik crowned as “Nugus Nagast” (king of kings), the first Ethiopian emperor. The confidence and pride provided by their biblical pedigree sustained Ethiopians every time they were faced with an existential crisis during their long history, and assisted them in repelling repeated Muslim and European invasions. To this day, the Lion of Judah is the Ethiopian national symbol.

After successfully overcoming an invasion by Fascist Italy between 1935 and 1943, Ethiopia’s slow progress towards development and growth was crushed for a generation by the establishment in 1974 of a communist dictatorship led by Menegistu Haile Mariam. By the time that regime was ousted in 1991, its 17 years of misrule had left the country in shambles as one of the poorest places on earth, riven by internal rebellions and unable to feed its own population. However, since then Ethiopia has decisively changed course, and it has become a star performer politically, economically, and diplomatically.

In the political realm, after enjoying remarkable stability and openness for a quarter-century, even if not yet a model of perfect democracy, Ethiopia is nevertheless one of the few African countries to hold mostly free, regular, and peaceful elections, resulting in a government that is among the most confident and legitimate of the continent. No less impressive is that this evident political stability occurs in a country that has a Christian majority alongside a significant Muslim minority—sustaining peaceful relations between religious communities while swiftly uprooting any surfacing militant or jihadist tendencies in their early stages. By a combination of vigilance, suspicion of activity by foreign Muslim organizations in Ethiopia, and swift action uprooting terror plots in their earliest stages, the Ethiopian government has succeeded to this point in neutralizing any serious internal Islamist threat. Moreover, in 2012 the Ethiopian political system even managed to overcome the death of its founding figure, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, without any political upheaval or instability—an occasion that speaks volumes about the maturity of its political system.

On the economic front, after the 2004 jettisoning of socialist economic policies and opening up to free enterprise, privatization, trade, and foreign investment, Ethiopia has experienced more than a decade of massive and sustained economic growth—around 10% a year. Significantly, since the country lacks the substantial oil or mineral resources of places like Nigeria and South Africa, this great economic progress is solely the product of entrepreneurship and hard work among the Ethiopian population—aided by a large expatriate Ethiopian community in the US and Europe that is investing funds and know-how in the mother-country.

Granting that it began from a very low base, Ethiopia’s economic growth over the last decade has nevertheless been nothing short of spectacular: GDP in 2006 was a mere 12.4 billion USD, but had increased more than four-fold by 2015, reaching an estimated 56 billion USD.[1] This fantastic rate of economic expansion, achieved despite a fast-growing population, has also undoubtedly benefited Ethiopians in absolute terms, as is evident from the growth of the GDP per capita, which in 2005 was a mere 169 USD, while by 2015 it was estimated to have surpassed 600 USD, a more than threefold increase in a decade. These economic numbers have translated into a steep improvement in the UN Human Development Index of Ethiopia’s population, which for the last several years has consistently placed it among the top 10 countries globally with the greatest annual human improvement. When considering the size of the population—some 90 million at last count—what is happening in Ethiopia today is probably the fastest and most extensive large-scale economic and social advance in the history of Africa.

With these political and economic successes and as the second most populous country in Africa, Ethiopia has naturally been increasing its diplomatic and military clout in the region for several years. Her leadership role in the African Union (headquartered in Addis Ababa), together with a willingness to assume significant regional security responsibilities in cooperation with the US and the West, Ethiopia is rapidly turning into the most important and reliable American ally in Africa. For more than a decade, Ethiopia has played a major role alongside the US in activities propping-up the feeble UN-recognized government of Somalia and fighting its Islamist enemies. Ethiopia is also regularly extending its protection to smaller political entities of the region, who are unable to fend off the Islamist threat on their own, such as the tiny city-state of Djibouti and the neighboring self-declared state of Somaliland in northern Somalia—both of minuscule size, but strategically placed at the entrance to the Red Sea, which controls the shipping lanes from Asia towards the Suez Canal and Europe. Moreover, Ethiopia’s peacekeeping forces deployed in South Sudan are playing a vital role in preventing an escalation of that conflict, and they are essentially the only thing preventing the brittle local cease-fire from descending into renewed civil war. Meanwhile, Ethiopia is also keeping an ever-vigilant eye on the antics of the erratic Eritrean regime, and occasionally reining-in that regime’s more rash and irresponsible actions—as when, some months ago, Ethiopia foiled the Eritrean attempt to exploit the chaos in Yemen and establish a military presence on the Hanish Islands, long disputed between Yemen and Eritrea.

On the diplomatic front, Ethiopia is investing considerable and sustained efforts both farther south and north. Towards the south, Ethiopia is building up a broad coalition of bordering African states sharing its political and economic outlook, with shared interests in regional stability and in fighting Islamist terrorism: Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Tanzania. The economic and strategic integration between these countries is being consistently strengthened, and Ethiopia’s building of the massive Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile is opening up prospects for exporting significant amounts of Ethiopian electricity to the energy-hungry countries of the area. Meanwhile, towards the north, the main Ethiopian goal has been to defuse the considerable opposition to the Renaissance Dam of downstream Nile countries Egypt and Sudan, who fear the negative repercussions on already meager water resources. The historic opposition of Egypt to the dam had in the past peaked repeatedly with threats of military action against the project, including declarations about sending the Egyptian Air Force to bomb the facility. By a combination of steady resolve and rhetorical moderation, undoubtedly aided by the recent internal disarray in Egypt, Ethiopia has successfully continued to build the dam project while also progressively defusing the Sudanese and Egyptian resistance. By initiating the “Nile Basin Initiative”, a 9-member forum based in the Ugandan city of Entebbe and including all the countries having some share of Nile waters (in addition to Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan, this includes Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Tanzania, with Eritrea as an observer), Ethiopia has turned the issue of Nile resources into a regional concern, instead of a merely Egyptian-Ethiopian dispute. Since the ingrained majority of members in the forum are from the energy-hungry upstream countries that stand to benefit from a supply of low-cost Ethiopian electricity, the Egyptians and Sudanese eventually realized that their downstream objections to the project would be consistently outvoted. Finding themselves diplomatically outmaneuvered and in no position to carry-out military threats, the Sudanese and Egyptians have had to settle on Ethiopian assurances that the dam will be filled in a gradual manner, so as not to drastically impair their water supply in any one year. But the end result of this process is of historic significance, since both Sudan and Egypt absolutely rely on the Nile water flow for their existence, and for the first time ever, they conceded effective Ethiopian control over them.

In many ways the diplomatic developments regarding the Renaissance Dam project reflect the emerging reality of the regional balance of power: there has been a momentous swing of strategic importance and roles, between Egypt and Ethiopia. For generations Egypt was the undisputed regional leader, while Ethiopia had to content itself with playing at most second fiddle—under Menegistu it even lost that role for a time. Since the removal of the communist dictatorship, Ethiopia has securely established its role as the clear economic and strategic powerhouse in northeastern Africa and beyond. Indeed, considering the mounting internal challenges faced by Nigeria and South-Africa, the other two leading African powers, if Ethiopia plays its cards well, it could very well emerge within a generation as the undisputed leader of the whole continent.

Ethiopia, a Christian-led country whose national symbol is the “Lion of Judah”—testimony to its ancient and persisting affinity with the bible and Jewish history—is today the only regional power with realistic prospects for containing the spread of the violent southern “Crescent of Chaos”. It has the ability and the political will to do so, and with Western backing and assistance it can achieve much more. Moreover, beyond dealing with immediate threats, Ethiopia is the only realistic long-term hope for an eventual rolling-back of regional chaos and violence, as well as for bringing some stability and one day perhaps even prosperity to places like South Sudan, Eritrea, or Somalia. In the face of the many threats emanating from the “crescent”, the US and its allies should not spare any effort in supporting and strengthening the rise of the Ethiopian Lion.

—

Dr. Ofir Haivry is Director of the National Strategy Initiative and Vice President at the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem. He has recently published pieces on Middle East regional strategy in Tablet, Al-Monitor, Commentary, and Mosaic.

[1] Final figures for the year 2015 have not been released yet.

—

Image: An illustration of the Resurrection from an 18th century Ethiopian psalter (St Andrews ms38900)

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024