Today happens to be National K9 Veterans Day, an opportunity to recognize the U.S. service dogs deployed in the nation’s defense in a number of vocational capacities: military, customs, search and rescue, police, secret service, airport security, FBI, and others. Joe White, A Vietnam veteran who witnessed the utility of service dogs, is credited with the idea of setting aside a national day to honor the dogs, proposing March 13th to commemorate the birthday of the U.S. Canine Corps, formed 75 years ago on this day in 1942 as a force multiplying resource—going places and detecting things that human beings cannot.

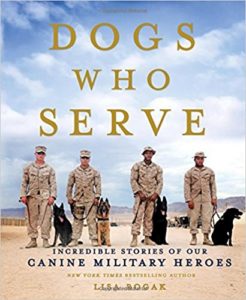

There will be scoffers of course. But a cursory look at Amazon will reveal upwards of a couple dozen recent books on service dogs, many written by veteran service dog handlers. Clearly there is an ample market of readers. One such book, Lisa Rogak’s Dogs Who Serve, is a compilation of short stories specifically about Military Working Dogs (MWDs) and their handlers.

Framing the particular stories, the book takes the wide-view, guiding readers through the various stages of a MWD’s career. We quickly discover that the process dogs face is not all that different from their two-legged military counterparts. Rogak guides us through the difficult selection of choosing dogs most apt to succeed, a process that begins in the dog’s whelping stage—their first 2-months of life. Selected dogs are then placed in foster care for 5 months where they are taught basic obedience and social skills by dog-loving families eager to help the military. Basic and advanced training follow, in which the dog begins service-specific training. MWDs are tasked with everything from sniffing out bombs or drugs, to patrolling, to jumping from helicopters and airplanes, to giving psychological comfort, and to providing basic physical protection and deterrence.

Personality matters, a successful MWD should be “inquisitive, eager to check out new places, sociable, not overly aggressive, and eager to play with objects.” For obvious reasons, dogs must be able to carry out their duties despite the circumstances of a combat environment, including loud noises, chaos, and extreme conditions. Specific personality traits point toward probably vocational specialties: for instance, a dog that likes playing with a ball and is reluctant despite the introduction of a strong aroma filling the air is usually more successful as a patrol dog. Those inclined to drop the ball to search out the source of the aroma will genuinely be successful as a detection dog.

Rogak then describes the arduous, months-long training that the dog and handler must endure as a pair. Mission effectiveness will depend on each one learning the other’s characteristics, being able to detect alterations in—and the meaning behind—even slight behavioral changes, and gaining the confidence of knowing what the other will do in a given situation. At times, everything rides on this: in many circumstances, the handler necessarily puts his or her life in the dog’s hands.

All along the way, as with any recruit, many dogs will wash out of combat training. Some fail because they lack the needed aggression. A number of these might leave the MWD program completely. Yet others will be redirected to non-combat roles, where they serve in roles not entirely dissimilar from the critical capacities provided by chaplains. For instance, Rogak tells us about Major Eden, a red Lab that washed out of training for being too “affectionate and sweet”. She went on to be a successful therapy dog stationed in Afghanistan in 2013 with her handler, PFC Alex Fanning. Fanning was a behavioral health specialist with the Ninety-Eighty Medical Detachment. Major Eden served as a magnet, drawing soldiers to her. Troops were often reluctant to talk about their problems or fears in a formal setting with a therapist, but Major Eden offered informal opportunities—and sometimes a gentle excuse–to talk with PFC Fanning. An abiding comfort, Major Eden would sit in on individual and group therapy sessions.

Major Eden’s is one of several stories that I particularly liked. There’s also Shamus, who helped a Marine combat veteran redeployed home to manage and predict his seizures. There’s Brit, the veteran explosives-detection dog whose presence on patrol added confidence and reassurance to green-troops newly deployed to combat. And then there’s Daysi—whose story brought tears to my eyes. Daysi had been a narcotic detection dog before being diagnosed with an inoperable tumor. Her handler decided to have Daysi euthanized, the hardest thing a dog owner can do. When the sad day arrived at Lackland Air force Base in San Antonio, the 802nd Security Forces personnel stood at attention, flanking the entrance to the animal hospital. As Daysi entered the hospital, guided by her handler, the airmen offered her a final salute, a fitting hero’s farwell.

There’s something significant in all this that should register for more than just dog lovers. Beyond the deep bound between dog and handler, military functionality, the psychological and emotional care the dogs provide wounded warriors, there is also the human to human bound the dogs help cultivate. When Diesel, a French RAID team dog was killed in anti-terrorist operations in the days following the Parisian attacks, the Russian counterpart of the French team presented the French with Dobryna, one of the Russian team’s own puppies. In Iraq, the dogs have played a role in helping navigate cultural divides, bringing Iraqi and American personnel into tighter cohesion.

Perhaps there is something spiritual in all of this. I have witnessed first-hand the bond human being s can forge with dogs: soldiers reenlisting just to remain with their service dogs, warriors giving their dog their own last bit of water. On the other side, some military dogs have had to leave service after losing their handler and being unable to make the move to another handler’s care. Perhaps all this points to dominion, to the responsible care that those made in God’s image have been called to exercise over creation. A responsibility that is not about domination, and in which real joy can be found. Moreover, if we really are fighting just wars then, just perhaps, there is something good and right in humanity and the beasts paired together against evil, and helping to bring about the conditions, however approximately, for all of creation to flourish again.

s can forge with dogs: soldiers reenlisting just to remain with their service dogs, warriors giving their dog their own last bit of water. On the other side, some military dogs have had to leave service after losing their handler and being unable to make the move to another handler’s care. Perhaps all this points to dominion, to the responsible care that those made in God’s image have been called to exercise over creation. A responsibility that is not about domination, and in which real joy can be found. Moreover, if we really are fighting just wars then, just perhaps, there is something good and right in humanity and the beasts paired together against evil, and helping to bring about the conditions, however approximately, for all of creation to flourish again.

—

Louis C. LiVecche Jr. is an Air Force veteran of the Vietnam War. His dog, Piper, spent eight years in a cage at a “puppy mill” before being adopted. They are good for each other. Over his lifetime, Louie has raised many dogs and other creatures, including—full disclosure—the managing editor of Providence.

—

top image: Chesty became Pfc. Chesty XIV on March 29, 2013 replacing Sgt. Chesty XIII as the mascot of the U.S. Marine Corps, housed at the Marine Barracks, Washington, DC. photo by Sgt. Dengier M. Baez/U.S. Marine Corps. For even more images of Military Working Dogs click here

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!