This article about national populism, trade liberalization, and the left-right divide on trade after Donald Trump became president first appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Providence‘s print edition. To read the original in a PDF format, click here. To receive future issues as soon as they are published, subscribe for only $28 a year.

They agreed. At least on the single issue of foreign trade, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton agreed the United States must retreat from free trade agreements. In the midst of the most polarized presidential election in living memory, both major party candidates converged on the need to reconsider American-led globalization and take a more protectionist stand in foreign markets.

Perhaps the only thing more surprising in the primaries and general election than Trump and Clinton’s convergence on their opposition to trade was that the issue was a talking point at all. International trade, after all, has generally been among the least important issues in recent U.S. elections.[1] Trade was once a very contentious issue in electoral debates. In fact, one Pennsylvania legislator in 1833 quipped that the definition of man ought to be changed to “an animal that makes tariff speeches”.[2] It would seem then that trade policy has once again become a relevant issue in American politics. The reemergence of trade, however, is noteworthy in the simultaneous dissolution of the left-right partisan split on the issue.

Throughout the developed world, the United States included, political parties tend to diverge on trade policy. Indeed, a left-right divide on trade policy has generally existed since the end of the Second World War.[3] However, the partisan division over foreign trade is seemingly at an end. Not only in the United States, but many in other advanced democracies are increasingly pulling back from foreign markets.

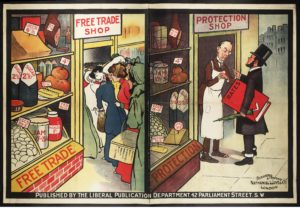

Representing the interests of labor, left-leaning parties approach trade liberalization with reservation and oftentimes advocate for protectionist policies. Building barriers to trade, the Democratic Party, for example, protects domestic manufacturing and accumulates support amongst trade union allies.

Right-leaning parties tend to advocate for the expansion of a free trade order. Allying with business leaders and owners of capital, Republican politicians regularly vote vigorously in favor of free trade agreements. It is from the right, however, that we see a sudden shift in trade preferences. While right-leaning parties still represent the interests of capital owners in the domestic economy, nationalism has led toward a rejection of the old regime in favor of protection.[4]

The Politicization of Trade Policy

The attack on trade from the right is not only new, but represents a shift from the general apathy with which politicians and voters have regarded trade policy during national elections. For the greater part of the last century, foreign trade has rarely been controversial in United States presidential elections. The 2016 presidential election, however, stands in stark contrast in the attention given to international trade agreements.

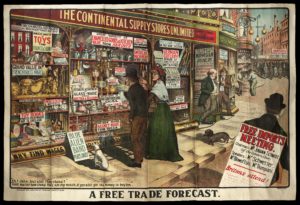

Before 2016, trade rhetoric was unusual in American elections. While candidates may have occasionally trumpeted one trade agreement or vilified a country for devaluing its currency to gain an unfair trade advantage, presidential candidates have seldom focused upon foreign trade in their national campaign strategies. Despite some agreements such as NAFTA garnering public interest, American voters are typically apathetic and ignorant with respect to foreign trade.[5]

In the past decade, political discussions of trade policy were all but unknown to American voters while foreign citizens responded with vehement polarization to trade agreements signed with the United States. Consider, for example, the passage of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). Costa Rican voters, on the one hand, demanded that the agreement only be ratified through a national referendum where voters narrowly approved CAFTA by a margin of 51-48. On the other hand, the U.S. Senate debated the agreement for less than four hours, and most American voters were unaware the trade agreement even existed.[6] Foreign legislatures have even devolved to violence over trade agreements. Such was the case in South Korea when a politician released a canister of tear gas in a vain effort to disrupt the vote to ratify the Korea-United States (KORUS) trade agreement.[7]

The 2016 election marked a notable departure from recent public opinion apathy over American trade policy. The prominence of foreign trade was on display beginning with the primary campaigns. Bernie Sanders rallied voters to trade protection through calls to “dump TPP” (Trans-Pacific Partnership),[8] and Trump vigorously criticized US trading relationships,[9] including when he called the TPP a “horrible deal” in one GOP debate.[10] Through boycotting Oreo cookies, Trump further politicized American trade deals as firms outsourced operations to foreign markets.[11]

This protectionist politicization continued into the general election campaigns as Trump used historic trade agreements to put Clinton on the defensive. Despite Clinton’s voting record against trade agreements, Trump used her marriage with Bill Clinton to associate her with the passage of NAFTA.[12] Clinton continued to affirm her opposition to unfair trade deals across the debates.[13] Meanwhile, Trump maintained his protectionist positions through calling NAFTA “the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere”.[14]

Since coming to office, President Trump has confirmed his commitment to protectionism. One of his first executive orders was to withdraw the U.S. from the TPP trade agreement.[15] Additionally, the president has called for the renegotiation of NAFTA and has pledged to pay for a Mexican wall using revenue from a proposed border-adjusted corporate tax scheme.[16] Surprisingly, even Canada has been criticized for benefiting from a “one-sided deal against the United States” when President Trump remarked that what Canada has “done to our dairy farm workers is a disgrace”.[17] Such protectionist rhetoric is even more uncanny given it is fueled by a Republican, the party that has tended to champion trade liberalization.

What can Trump and Clinton teach us about Americans’ trade attitudes? The 2016 election suggests that voter preferences have largely converged toward protectionism. In a political landscape increasingly characterized by polarization and partisan bubbles, it is all the more marvelous that an electorate would agree on anything, let alone foreign trade policy.[18] However, this change in voter trade attitudes seemingly conflicts with prevailing economic expectations.

Old Parties & Old Divisions

For decades Democrats in Congress have generally blocked new trade agreements while Republicans have supported such legislation. Meanwhile, presidents from both parties have consistently supported free trade since the end of WWII. Because presidents must appeal to voters across all districts, they tend to pursue general welfare and consumer interests over varied industry interests.[19] Some industries like those in Silicon Valley are clear beneficiaries from globalization while others are vulnerable to increased foreign competition.

The recent congressional fight over the Trans-Pacific Partnership exemplifies the old partisan divisions on trade policy. Despite being promoted by President Obama, most Republicans supported the agreement. Even while holding their nose at joining hands with the president, constituent interests once again led right-leaning politicians to vote for trade expansions. Ironically, it was the Democratic Party that critically resisted the administration and vocally opposed TPP ratification.

Old Parties & New Alliances

Because both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump politicized the dangers of foreign trade, voters are reacting uniquely to trade policy vis-à-vis other economic policy areas. Clinton’s protectionist rhetoric is easily predicted by classic trade divisions; after all, the Democratic Party has long championed the causes of labor.[20] Trump’s fervent demands to increase trade protection, however, is peculiar given the Republican Party, like other right-leaning parties, tends to represent the interests of capital.[21]

If citizens from the left and right vary in how they benefit from free trade, then the protectionist rhetoric adopted by Trump and Clinton seemingly indicates that some voters are rallying in spite of their self-interest. Perhaps citizens were never too mindful of their self-interest when it came to trade, but we could not tell because trade had not been a salient electoral issue.[22]

Does economic self-interest no longer determine voter trade preferences? In short, not necessarily. Donald Trump may have spurned the Republican Party’s traditional stance on trade, but his tax proposals did not stray from typical Republican fare.[23] While this may seem perplexing to some, it serves as further evidence that Trump strategically pivoted on trade to electorally gain from the new determinant of trade attitudes: national populism.

Unlike the nationalism that wrought conflict throughout the 20th century, national populism is not adventurous, but it is inward looking. Voters are increasingly divided, therefore, along a new cleavage of open vs. closed. Elections across the world have seen this new form of nationalism run rampant in right-leaning parties. Like other foreign policies such as immigration, trade is now regarded more through the lens of national populism and less on its welfare effects upon the economy.

National populism and trade protection went hand-in-hand in European elections as British and French voters flexed their collective and reactionary strength against their countries seemingly immutable integration into global markets. Brexit took the world unawares as British voters cast aside their nation’s role in the European project. Without precedent, the Communist and National Front candidates, both outspoken in their condemnation of globalism, combined for 41% of the French vote share in the first round of the presidential election.[24]

Even before Donald Trump’s victory, some political scientists argued that out-group fear and nationalism may drive preferences for trade protection.[25] Donald Trump may simply have vilified trade agreements to evoke nationalism and out-group anxiety. Attitudes on trade, like those on immigration, may be more determined by perceptions of cultural consequences than by material well-being.[26]

As elections around the world experience a rise of nationalism, we may no longer see a left-right divide on trade. Left-leaning parties that have historically opposed trade in the interest of labor may unite with rightist parties on this one issue. Even parties with a track record of trade liberalization may abruptly shift and adopt protectionist rhetoric so as to benefit from the tide of national populism.

Donald Trump has taught us that, at least for the time being, American trade attitudes are driven less by material self-interest and more by national populism and global anxiety. With the post-election realignment of politics in Europe and the United States, parties are entrenching themselves for upcoming electoral battles. In the midst of this stark polarization, parties on the left and right may find all too much agreement in their willingness to construct new walls to global trade.

If the United States is to return to its position of promoter and guarantor of free trade, a political champion of global integration must emerge. Future electoral battles, however, may not necessarily be fought along the traditional left-right divide. Instead, a new open vs. closed electoral cleavage in national politics may develop, where integrationists compete against protectionists in casting their visions for American growth and strength.

—

Timothy W. Taylor is Assistant Professor of Politics and International Relations at Wheaton College

Feature Photo Credit: Container Docks in Houston, Texas. By Louis Vest, via Flickr.

[1] For empirical evidence for the low electoral importance of trade in the U.S. see, for example, Guisinger, Alexandra. 2009. “Determining Trade Policy: Do Voters Hold Politicians Accountable?” International Organization, 63 (3): 533-557; Taylor, Timothy W. 2015. “The Electoral Salience of Trade Policy: Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Welfare and Complexity.” International Interactions 41(1): 84-109.

[2] Shepard, William B., Representative. 1833. Speech. Register of Debates in Congress. Vol. 9. Part 2. Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1434-1478.

[3] Milner, Helen V. and Benjamin Judkins. 2014. “Partisanship, Trade Policy, and Globalization: Is There a Left–Right Divide on Trade Policy?” International Studies Quarterly, 48 (1): 95-119.

[4] In terms of domestic economic policies such as taxes and government spending, it was business as usual for the Republican primary candidates. The same candidates, however, noticeably took a more protectionist stand on foreign economic policies.

[5] Guisinger (2009)

[6] Jimenez, Marianela. “Costa Rica to Join Free Trade Agreement.” Washington Post, October 8, 2007.

[7] “South Korean Lawmakers Tear Gas Rivals.” New York Post, November 22, 2011.

[8] Corasaniti, Nick. “Bernie Sanders Hones Anti-Trade Message for Illinois and Ohio.” New York Times, March 11, 2016.

[9] Krugman, Paul. “Trade and Tribulation.” New York Times, March 11, 2016.

[10] “Rand Paul embarrassed Donald Trump over China and the TPP during the GOP debate.” The Week, November 10, 2015.

[11] Farley, Robert. “About Trump’s Oreo Boycott.” Fact Check, November 19, 2015.

[12] Montanaro, Domenico. “A Timeline of Hillary Clinton’s Evolution on Trade.” NPR, April 21, 2015.

[13] Wolf, Jim. “Hillary Clinton Slams Proposed U.S.-Korea Trade Pact.” Reuters, June 9, 2007.

[14] “Presidential Debate: Trump, Clinton clash at fiery first debate on trade, tax returns, temperament.” Fox News, September 26, 2016.

[15] Mui, Ylan Q. “President Trumps Signs Order to Withdraw from Trans-Pacific Partnership.” Washington Post, January 23, 2016.

[16] Weinstein, Austin, Justin Sink, and Joshua Green. “Trumps Warms to House Republicans’ Proposed Border-Adjusted Tax.” Bloomberg, January 26, 2016.

[17] Robertson, Lori. “The U.S.-Canada Dairy Dispute.” FactCheck.org, April 28, 2017.

[18] Darcy, Oliver. “Obama: America’s Retreat into Partisan ‘Bubbles’ Represents ‘Threat to Our Democracy’.” Business Insider, January 10, 2017.

[19] Lohmann, Susanne and Sharyn O’Halloran. 1994. “Divided Government and U.S. Trade Policy: Theory and Evidence.” International Organization, 48 (4): 595-632.

[20] Schlozman, Daniel. “The Alliance of U.S. Labor Unions and the Democratic Party.” Scholars Strategic Network, October 2013.

[21] Dutt, Pushan and Devashish Mitra. 2005. “Political Ideology and Endogenous Trade Policy: An Empirical Investigation.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 87 (1): 59-72.

[22] Taylor, Timothy W. 2015. “The Electoral Salience of Trade Policy: Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Welfare and Complexity.” International Interactions, 41 (1): 84-109.

[23] Hedrick, Brian. “Trump’s Tax Plan Is More of the Same from Republicans.” The Hill, October 3, 2010.

[24] National Front candidate Marine Le Pen won 21.6 percent, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the far-left candidate, won 19.5 percent.

[25] Mansfield, Edward D. and Diana C. Mutz. 2009. “Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest, Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety.” International Organization, 63 (3): 425-457.

[26] Margalit, Yotam. 2012. “Lost in Globalization: International Economic Integration and the Sources of Popular Discontent.” International Studies Quarterly, 56 (3): 484-500.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024