If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do? Psalm 11:3

The security environment changed abruptly in Europe with the Russian annexation of Crimea. Moscow used the brilliant tactic of having its special forces soldiers suddenly appear at strategic locations throughout this important Ukrainian province. Since the soldiers did not wear national insignia, the media dubbed them “little green men,” and without firing a shot they forced Kiev to give up Crimea. This was followed by a Kremlin-inspired and -led separatist movement in Ukraine’s eastern provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk. Despite dithering and indecision among Western leaders, Ukraine fought back, and what Moscow viewed as easy prey turned into an ongoing costly three-year war. Yet, Russian meddling in Ukraine should not have come as a surprise as the Kremlin under Vladimir Putin already had a reputation for intervention and interfering in neighboring nations.

The first sign of a shift in Moscow’s approach to its neighbors occurred in 2007 when Estonia decided to move a Soviet-era statue from its capital of Tallinn to outside the city. This “Bronze Soldier” monument became a shrine for the nation’s ethnic minorities, and Moscow intimated that there would be consequences if it was moved. Not wanting to be bullied by its meddling neighbor, Estonia moved the statue, and in response, it was crippled by a debilitating cyber-attack.

The next year, Russia invaded the nation of Georgia, occupying two large regions of that nation: Abkhazia and South Ossetia. This, followed by the ongoing war against Ukraine, serves as ample evidence of Putin’s desire to reassert Russian influence and power in Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. The challenge for Moscow to impose its will in Northern and Eastern Europe is a bit more complicated as many of the nations in its crosshairs are NATO members. To accomplish this end, Putin needs to diminish the credibility of NATO, especially in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. This can take the form of (1) attacking directly or (2) using ambiguity in the form of disgruntled “local” ethnic Russians to rise up in rebellion and thereby create conditions for a Russian intervention.

Launching a conventional attack on Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania would be too risky as it would result in action by NATO. However, this option is not completely off the table and would happen if American leadership in NATO was perceived as weak. If this “unthinkable” scenario transpired, Russian forces would rush across the Baltics, slicing through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Victory would have to be swift to prevent NATO reinforcement. The goal would be to seize the airports, seaports, major road networks, and capital cities to control all three of the nations. This high-risk attack would focus cutting off NATO’s land access to Central Europe, focusing on the Suwalki Gap. The Suwalki Gap is a 65-mile-wide land corridor that connects Lithuania to Poland. To the west of Suwalki is the Russian military base and enclave of Kaliningrad, and to the east is Belarus, a staunch ally of Moscow. From these locations, the gap could easily be severed, making the closure of this narrow land corridor relatively easy. With land access closed, and air/sea access risky, Moscow could declare a fait accompli and anticipate that NATO would not launch a costly counterstrike. Yet, such an attack would be far too risky for Moscow, with the resulting economic and military consequences potentially destroying Russian power.

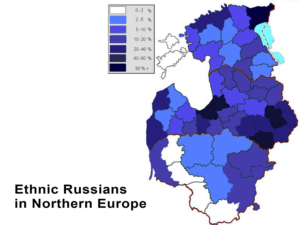

To avoid a direct confrontation with NATO, the Kremlin is more likely to use a strategy of ambiguity to attack one the Baltic nations. This would look similar to the 2014 Moscow-exported civil war it fomented in eastern Ukraine. Focusing on areas with a high ethnic Russia population in Latvia and Estonia (Lithuania’s ethnic Russian population is less than 6 percent), the separatists would actually be civilian-clothed Russian Special Forces and not “little green men” as seen in Crimea. They would claim to be local civilians seeking independence for the “discrimination” that they suffered from Estonians or Latvians. Moscow’s goal would be to destabilize the region without direct evidence connecting it to the Kremlin. This ambiguity would not just provide Putin plausible deniability, but, more importantly, it would cause the NATO Alliance to delay taking action. As the crisis spun out of control, the stage would be set for a Russian intervention. If NATO acted decisively, Putin would simply back off and claim that he had nothing to do with the trouble. If NATO dithered, the stage would be set for a limited military intervention to assuage the suffering of the ethnic Russian woman and children living in the besieged region of Estonia or Latvia. Although Moscow would offer pledges of withdrawing once the crisis was over, before they actually leave, a referendum in the occupied territories would occur, voting overwhelmingly in favor of Russian annexation. Thus, without going to war with NATO, Moscow could defeat NATO.

To avoid a direct confrontation with NATO, the Kremlin is more likely to use a strategy of ambiguity to attack one the Baltic nations. This would look similar to the 2014 Moscow-exported civil war it fomented in eastern Ukraine. Focusing on areas with a high ethnic Russia population in Latvia and Estonia (Lithuania’s ethnic Russian population is less than 6 percent), the separatists would actually be civilian-clothed Russian Special Forces and not “little green men” as seen in Crimea. They would claim to be local civilians seeking independence for the “discrimination” that they suffered from Estonians or Latvians. Moscow’s goal would be to destabilize the region without direct evidence connecting it to the Kremlin. This ambiguity would not just provide Putin plausible deniability, but, more importantly, it would cause the NATO Alliance to delay taking action. As the crisis spun out of control, the stage would be set for a Russian intervention. If NATO acted decisively, Putin would simply back off and claim that he had nothing to do with the trouble. If NATO dithered, the stage would be set for a limited military intervention to assuage the suffering of the ethnic Russian woman and children living in the besieged region of Estonia or Latvia. Although Moscow would offer pledges of withdrawing once the crisis was over, before they actually leave, a referendum in the occupied territories would occur, voting overwhelmingly in favor of Russian annexation. Thus, without going to war with NATO, Moscow could defeat NATO.

In such a scenario, the key to security and stability in the Baltics rests with ethnic Russians in Estonia and Latvia. Although sources differ considerably on the actual numbers of ethnic Russians residing in the Baltics, a recent study by the United Nations put it as high as 37.2 percent in Latvia and 29.6 percent in Estonia. In some areas, such as Narva, Estonia, or Riga, Latvia, the overwhelming majority of the population is Russian. Fortunately for the Baltics, the ethnic Russians in their nations are not a monolith and diverge in their outlook in regards to Moscow.

There are roughly four groups of ethnic Russians who need to be considered when developing an approach to earn their trust and support. This includes the following:

- Old Believers

- Economic Migrants

- Retired Soviet Officials and Military

- The EU/NATO Generation

The first group is called the “Old Believers,” also known as the “Old Ritualists.” The Old Believers broke off from the Russian Orthodox Church after a series of reforms were undertaken in 1666 to modernize/standardize the denomination’s liturgy. A faction in the Russian Orthodox Church rejected the reforms, clinging to the traditional liturgy. In 1685, Moscow unleashed a persecution of this group, causing many of them to flee and settle in Ukraine, the Baltics, and elsewhere in Europe. The Old Believers are a distinct Russian subgroup generally not susceptible to Moscow’s propaganda or gamesmanship.

The next group includes those Russians who migrated to the Baltic region after World War II for economic opportunity. With the encouragement of Stalin, who nefariously endeavored to alter the region’s demographics, ethnic Russians settled in Estonia and Latvia to improve their wellbeing. Groups of Russians also endeavored to settle in Lithuania, but most fled during a decade-long insurgency after World War II led by the “Forest Brothers.” The Forest Brothers were Lithuanian patriots who waged a guerilla war to force out the Russian economic migrants. This is why in large part only 5.8 percent of Lithuania’s population is ethnic Russian. Estonia and Latvia also had their version of the Forest Brother uprising, but it was far less successful.

The next group includes those Russians who migrated to the Baltic region after World War II for economic opportunity. With the encouragement of Stalin, who nefariously endeavored to alter the region’s demographics, ethnic Russians settled in Estonia and Latvia to improve their wellbeing. Groups of Russians also endeavored to settle in Lithuania, but most fled during a decade-long insurgency after World War II led by the “Forest Brothers.” The Forest Brothers were Lithuanian patriots who waged a guerilla war to force out the Russian economic migrants. This is why in large part only 5.8 percent of Lithuania’s population is ethnic Russian. Estonia and Latvia also had their version of the Forest Brother uprising, but it was far less successful.

The third group includes former members of the Soviet government or military personnel who, after retiring from their posts during or shortly after the Cold War, decided to stay in the Baltics. The region’s comparative moderate weather and better economic conditions appealed to many of them, especially those from the hinterlands of Russia. These retired Cold War officials tend to reside in locations where there were Soviet government offices or Soviet military bases. This group has a natural and material allegiance to Moscow that would be daunting, if not impossible, to overcome.

The fourth and final of the ethnic Russian groups living in the Baltics is the EU/NATO Generation. This group includes young people largely under thirty years of age whose education and life experiences make them less susceptible to Russian propaganda. Growing up in the post-Cold War world, they did not experience the depravations of the Soviet era, but rather witnessed the transformation of the region to the economic prosperity that it enjoys. More importantly, this generation enjoys the blessings of freedom, the benefits of having a European Union passport, and the security umbrella provided by NATO.

Should Moscow consider fomenting an ethnic uprising in the Baltics, the group that provides the greatest opportunity are the retired Soviet officials. They have a natural loyalty to Mother Russia that is born forth by their years of service during the height of Soviet power. Not only do they ideologically relate to Moscow, but they also receive monthly financial benefits as well, averaging around 200 euros a month (depending on one’s rank at retirement during the Soviet Empire). This “stipend” goes a long way in parts of the region and is a certain way to ensure the fidelity and loyalty of a segment of the population residing outside the geographic borders of Russia. The level of influence that these Kremlin proxies have over their respective regions varies, but can be considerable where there is a high percentage of retired Soviet officials on the dole from Moscow. An example of the impact of this is evident in Daugavpils, Latvia.

Situated two hours east of Riga and close to the Belarusian border, Daugavpils boasts a large ethnic Russian population. It is economically depressed with a portion of the population receiving monthly benefits from Moscow. The city hosted several Soviet bases during the Cold War, and many of these Soviet military and government workers remained in Daugavpils and receive retirement checks from Moscow. Compounding the problem, most people in this part of Latvia get their political views and news from Russian TV. Moscow pours a seemingly endless stream of propaganda that stirs hostility towards the United States and NATO while advancing Moscow’s worldview. Coincidently, it was the only place in the Baltics where, as we checked into the hotel, our hostess grumbled that we were in Daugavpils to cause trouble (war mongers). While there we also viewed a video of a local ethnic Russian yelling profanities at the U.S. Army’s Second Cavalry Regiment when it passed through the town earlier in 2017 as part of the NATO mission in the country. In every case except one, when we asked locals their views of NATO, the United States, and Moscow, they cautiously looked around to see who was listening before answering our questions. Clearly, it is unfair to judge a region based upon a few encounters, but it does reflect a general mood that influences Daugavpils.

Daugavpils seems far removed from Riga in more than a geographic manner. It felt a world apart economically, culturally, as well as politically. In previous studies on this topic, our focus was Narva, Estonia, which likewise is predominantly ethnic Russian, and the furthest eastern point of the NATO Alliance. However, Narva does not seem “forgotten” and is making strides economically. Such a positive trajectory was not evident in Daugavpils. The economic depression here seems to have bred a hopelessness among a segment of the society, making this region particularly vulnerable to Moscow’s exploitation. Adding to the danger is that the groundwork is being laid every day across the Baltics with the barrage of Russian television broadcasting propaganda to the Russian diaspora scattered in the region. This long-term investment is estimated to cost Moscow one million euros a day, with the Baltic and NATO response to counter the propaganda palling in comparison. With the consequential economic depression, the heavy influence of Russian propaganda, the presence of former Soviet officials receiving a monthly check from Moscow, and being far from Riga in so many ways, Daugavpils appears to be NATO’s “soft” underbelly.

The impression in the Baltic Region that the strategic and operational environment is turning in NATO’s favor is true, but significant vulnerabilities remain. Daugavpils is just such an area that requires attention to reduce its susceptibility. Of the four basic groups of Russians identified earlier, it is unlikely that the hearts and minds of the retired Soviet officials could ever be won to a favorable view of NATO. They receive monthly annuities from Moscow, and it would be foolish for them to turn on the Kremlin and thereby “bite the hand that feeds them.”

One Latvian who invests her time and energy on achieving greater reconciliation with the local Russians on what can be done to bridge the ideological gap responded that they need “time” to win the preponderance of ethnic Russians in the region. Time is precisely what NATO can give the Baltics if it continues to develop a viable and credible deterrence posture in the region. The hope is that the preponderance of the post-Soviet generation will have the education and vision to see beyond the propaganda generated from Moscow and develop an identity of being an ethnic Russian Latvian, or ethnic Russian Estonian, willing to defend the nation from any foreign invader, whether from Moscow or elsewhere.

Yet, this is a tall order and requires more than time, but some sort of national service to provide an opportunity for the local ethnic Russians to live and work outside of their enclaves would be beneficial. Of the three Baltic nations, only Latvia does not have some sort of compulsory military service, which makes it difficult to foster a truly “Latvian” identity amongst the post-Soviet generation.

During a recent meeting with a Baltic official, I posed the question on what could bridge the gap between ethnic Russians and ethnic Estonians and Latvians. The answer was surprising: he said that Christianity is the greatest hope for the region. The brilliance of his answer did not escape me. Rampant secularism and political correctness have blinded the eyes and thinking of many in “the West” to the importance and legacy that Christianity continues to have on society. It was precisely this legacy that this Baltic official honed in on. He spoke of free speech, the republican type of government, the value of human life, and freedom in general. This worldview, like it or not, laid the foundation for the freedoms and prosperity that “Western” nations enjoy today. Rewriting textbooks and living in ignorance of historical facts does not change this. This official spoke of engaging the leaders of the Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches to ascertain what they could do to educate the people of the important contribution that Christianity has made to their society and how it created the basis for the freedoms that they enjoy today.

Russian disinformation blasted to its ethnic brethren in the region is a grave concern. However, in the long term, the revival of paganism and the legacy of atheism, left behind from the failed communist experiment, may be the greatest threats facing the Baltics in generations to come. Neither atheism nor paganism has a worldview that supports the freedoms that so many of us take for granted today. It is the hope that the people of the Baltics will remember their common Christian worldview, and this remembrance will serve as the catalyst to forge three nations that will not so easily be undermined by the Kremlin or any other meddling power. The ethnic divide in areas of the Baltic region is deep and far-reaching. Divergent interests, experiences, and worldviews exist, and overcoming the legacy of Soviet abuses is not easy to forget. It will take at least one generation before the ethnic divide will be bridged between Russian and Latvian, and Russian and Estonian. Yet, the hope for a better future is built on more than time, but also the security provided by forces from across NATO and the legacy/influence of Christianity. This shared history may just bridge the ethnic gap in the region and keep the Baltics free.

—

Colonel (COL) Douglas Mastriano, a veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, began his career in the 1980s, serving along the Iron Curtain with the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment. Since then, he has served at tactical, operational, and strategic levels of command ranging from the 3rd Infantry Division (Rock of the Marne), to the Pentagon and in NATO. COL Mastriano has a Masters in Military Operational Art and Science, Masters in Strategic Intelligence, Masters in Airpower Theory, a Masters in Strategic Studies, Bachelors in History, and a PhD in History from the University of New Brunswick. Doug’s book, Alvin York: A New Biography of the Hero of the Argonne, is an award-winning biography on America’s greatest First World War hero. Doug led the expedition to locate where Alvin York fought in 1918 and earned the Medal of Honor. American and French authorities endorsed Doug’s efforts, which led to the construction of a five-kilometer historic trail, replete with monuments and historic markers in the Argonne Forest, France, for visitors to walk where Sergeant York fought. His website www.sgtyorkdiscovery.com has details and maps. COL Mastriano teaches strategy at the U.S. Army War College.

Photo Credit: Narva, Estonia, the furthest eastern point of NATO. On the left is Narva, Estonia, and the right is Ivangorod, Russia. Photo provided by COL Mastriano.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024