The Ghost: The Secret Life of CIA Spymaster James Jesus Angleton is the latest book on the legendary longtime counterintelligence chief who divided his own agency and much of Western intelligence with his conspiracy theories. He was by most accounts brilliant, mesmerizing, a poet-intellectual, and a patriot. And by other accounts he was, at least in his later years, paranoid, insane, alcoholic, and obsessed with the Soviet Union’s almost irresistible master plot to subvert the West.

Angleton rose through the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, precursor to the CIA) in World War II, was among the CIA’s founders, helped block the Communist Party in early Cold War Italy, ran covert operations in Eastern Europe, and became the decades-long chief liaison with Israel. He also became a fierce Zionist who helped build America’s special friendship with the Jewish state, despite his youthful antisemitism and admiration for Mussolini plus a personal friendship with fascist mouthpiece Ezra Pound.

In Washington, Angleton enjoyed long boozy lunches with his British intelligence counterpart Kim Philby, who he confided in, sharing secrets even as others suspected what Philby actually was: a Soviet agent. Philby’s 1963 defection to the Soviet Union compounded Angleton’s by then growing paranoia.

In Washington, Angleton enjoyed long boozy lunches with his British intelligence counterpart Kim Philby, who he confided in, sharing secrets even as others suspected what Philby actually was: a Soviet agent. Philby’s 1963 defection to the Soviet Union compounded Angleton’s by then growing paranoia.

Two Soviet defectors would help push Angleton over the edge. Anatoliy Golitsyn came to him in 1964 and fed him all that he feared and suspected as CIA’s counterintelligence chief, mainly that his agency was penetrated by a Soviet mole. Golitsyn was shortly followed by Yuri Nosenko, who rebutted many of Golitsyn’s claims. Angleton lavished trust and secrets on Golitsyn while denouncing Nosenko as a KGB dispatched imposter. For several years, Nosenko was imprisoned and tormented as the CIA, at Angleton’s urging, tried to extract his confession, for which the CIA would later apologize and award a pension.

Angleton for years strove to unearth the supposed mole, destroying careers and rejecting other Soviet defectors with counterclaims. He accepted Golitsyn’s extraordinary yarns about KGB and Soviet global omnipotence, including that the USSR-China rift was merely a facade to deceive the West. In later years, Golitsyn would warn that the rise of Solidarity in Poland, Gorbachev’s glasnost, and even the Soviet Union’s collapse were all KGB deceptions to lull the West into complacency.

Angleton’s conspiratorial obsessions became so divisive and destructive that eventually he was fired in 1974. His successor as counterintelligence chief would quit within two years, explaining no man could sanely sustain chronic suspicion any longer. Summoned before a Senate Committee in 1975 over his role in domestic spying, Angleton defiantly insisted that in some cases the CIA should defy presidential instruction. Now in the public eye, he became infamous and legendary. He embodied mystery, secrecy, and deception.

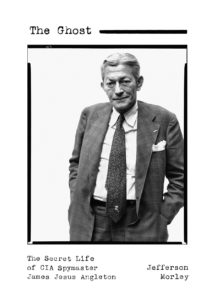

As a college student, I once encountered him on an elevator. He was in his usual dark overcoat, black homburg, and large glasses, tall and cadaverous with a craggy face. He smiled wanly at me. I was thrilled to be in his ominous presence.

No doubt Angleton enjoyed his notoriety as he continued in retirement to push his storyline of the Soviet master plot. He blamed the USSR for his ouster, which he thought his old friend and then nemesis Kim Philby orchestrated from his KGB perch in Moscow. Angleton died in 1987 a few years before the Soviet Union’s implosion, which perhaps he would’ve disbelieved as just more KGB deception and more endless conspiracy.

The author of this new book, Jefferson Morley, is a conspiracist himself and conjectures Angleton had some role in President Kennedy’s assassination. Morley does admit there’s no conclusive evidence, other than Angleton’s having tracked Lee Harvey Oswald for years as a leftist who defected to the Soviets and later approached the Cubans. Angleton naturally insisted the KGB had killed JFK.

Reportedly, Angleton refused last rites before dying by explaining he had his own religion. His faith seemed to preclude confidence in divine sovereignty, instead of trusting that fallen, frail humanity can seamlessly sustain trans-generational conspiracies that defy the deity in perpetuity. Angleton also seemed to believe that open democracies possibly could not defend themselves against disciplined dictatorships. He underestimated the disinfecting advantages of open debate and transparency among a free people versus the ultimately self-destructive self-deception required by coercive dictatorships.

Angleton thrived on conspiracy theories and in turn generated countless ones about himself. His myopic search for an apparently nonexistent mole in the end destroyed him. Ironically, his paranoia and obsessions maybe helped to ensure there was no actual mole during his decades at CIA. Perhaps democracies sometimes need such a “ghost” to conjure the very worst fears about their enemies. But ideally the spies for democracies have more confidence in their free society and more faith that Divine Sovereignty cannot be forever defied, not even by the greatest conspiracies.

—

Mark Tooley is president of the Institute on Religion & Democracy and editor of Providence.