The norms and practices of international diplomacy, the unwritten laws which govern affairs between nations, are not naturally fixed or universal among mankind. They are rather a consensus built upon centuries of commerce, political dialogue, ideological disputes, and war. Four hundred years ago last month on May 23, 1618, the Second Defenestration of Prague took place. By throwing the representatives of the Austrian emperor out a window, the Bohemians (Czechs) started the Thirty Years’ War, the apocalyptic culmination of the religious and political divisions created by the reformation. This single event changed the course of world history and, 30 years later, led to the Peace of Westphalia and the beginnings of the nation-state world order.

The seeds of this conflict were sown in 1517 when a monk named Martin Luther nailed a document called the Ninety-Five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg. Written in Latin, the document was meant to be a call for scholarly debate about reforming abuses of the Catholic Church, in particular the Papal abuses with regards to issuing indulgences. Soon the document was translated and spread across Europe, causing a fervor as it spoke to a desire for reform held by many in Western Europe. This theological dispute quickly took a political dimension as the pope and local Catholic bishops refused to debate Luther on theological grounds. Rather, they argued that the pope, as archbishop of Rome and the heir to Saint Peter, had final jurisdiction over theological issues and that, since previous popes considered the practice to be consistent with Christian theology, the authority to issue indulgences was valid regardless of perceived abuses. This conflict between religious theology and political authority came to a head at the Diet of Worms, where Luther refused to recant of his views unless he could be convinced through arguments based on the Bible and reason. As a result, the pope excommunicated him and thus opened up a permeant rift between the two camps.

Previously, Catholic Europe had been united in a single political, cultural, and religious entity known as Christendom. Arising out of the ruins of the Western Roman Empire, it recognized universal dominion of the Catholic Church over religious and in many cases secular affairs. Those who were not members of the Catholic Church, such as Orthodox Christians, Jews, and Muslims, were not considered to be part of Christendom and often existed on the margins of society. Thus, the split between those who would later be called Protestants and Catholics could not remain strictly a theological dispute. It was accepted that a Christian sovereign should defend the true religion, promote peace, and rule justly. These objectives quickly came into conflict once the Protestant Reformation created religious pluralism, and especially when one side rejected the very authority which held the whole political system together.

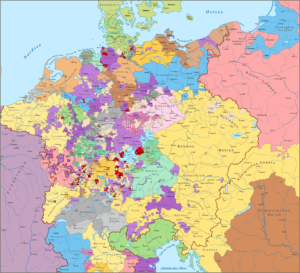

Religious tension within the Western world soon inflamed all the other ethnic, economic, and social issues that had been simmering in the post-Medieval period. Social order broke down as communities were unable to cope with the splintering polity. From 1517 until 1618, Europe was thrown into chaos as revolts, civil wars, and national conflicts flared across Europe. Many attempted to bring about a social-religious settlement by either force or negotiation, but no universal solution had been found by 1618.

Into this, a man named Ferdinand II assumed the crown of Austria upon the death of his uncle in 1617. Ferdinand was known for his support of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and had purged his personal lands of Protestants prior to assuming the crown. This naturally concerned his new subjects in the Kingdom of Bohemia, who were overwhelmingly Protestant. An elected monarchy, the Bohemian estates assembled and elected Ferdinand as king but also demanded that he recognize their rights, privileges, and religious liberties, granted to them by his uncle. When Ferdinand started implementing policies discriminating against the Protestants, the estates protested, but Ferdinand decided to dissolve their assembly. In reaction to this, a Protestant mob gathered in Prague, forced itself into the castle where the imperial representatives were staying, and threw them out a third-story window. Thus, Europe was unknowingly plunged into the most destructive war in its history.

What started on May 23, 1618, ended 30 years later with the Peace of Westphalia. By that time, almost every nation in Europe had participated directly or indirectly in the war. In terms of percentage of the population, more Europeans died in the Thirty Years’ War than in World War II. In Germany, the war’s primary battleground, one-third of the population lay dead, and the population level did not return to its pre-war numbers until the 1800s. The political system that had governed Western Europe before the Reformation also died. Catholic and Protestant diplomats, staying in different cities and sending messages via riders because the pope had condemned the peace talks, hammered out the Peace of Westphalia after five years of negotiations. It established the state with “Westphalian sovereignty” as the basis of a new Western European order and recognized diplomatic equality among all participating states. It also recognized the rights of the heads of state to determine the religious situation within their own lands and which denomination would be their state religion. After over 100 years of political, religious, and social discord, a new political order had been established in the West.

Four hundred years later, the Defenestration of Prague is recognized as the beginning of a culminating event which ended one international order and created another. This order was shaped by those who had lived through the conflict and recognized the practical need to establish a new system to end the chaos and destruction caused following the breakdown of Christendom. Since then, the nation-state system has spread to encompass the world despite the attempts of ideologies such as fascism and communism to overthrow it. It was then, as it is now, shaped by ideas, individuals, and nations.

The Defenestration of Prague should be remembered and serve as a reminder that the liberal international order is not indestructible. In an age of unprecedented global prosperity but also global unrest and uncertainty, the price of its collapse could be incalculable, and there is no certainty of what would emerge from its ruins. It is therefore imperative that virtuous men and women guide the world forward with one eye toward the future and one eye toward the past, where the lessons of a ravaged Europe lay.

—

Justin Roy holds a Masters in history from the University of San Diego with an emphasis on Middle Eastern history.

Feature Image Credit: Battle of Rocroi, by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, via Wikimedia Commons.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!