For four years a war has raged in Yemen, and few if any in the West have paid attention. The reasons given for this apathy are many: Yemen is hard to find on a map. The Middle East is a mess. It’s one more pointless war among many. Most Americans are too obsessed with domestic politics to direct their gaze to this obscure Gulf state.

Recently, though, a few people have begun to take notice. Yesterday, Nicholas Kristof launched a blistering attack against the Trump administration for crimes against humanity—yes, crimes against humanity—in Yemen. “President Trump didn’t mention it at the United Nations,” Kristof writes, “but America is helping to kill, maim and starve Yemeni children… Our behavior is just unconscionable.”

Kristof cites the use of American bombs to blow up a school bus, a funeral, and a market in recent months, acknowledging that Arab forces pulled the trigger but also blaming the US for supporting them. “The United States is not directly bombing civilians in Yemen, but it is providing arms, intelligence and aerial refueling to assist Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates as they hammer Yemen with airstrikes, destroy its economy and starve its people.”

Why is America engaging in such immoral behavior? Simple, Kristof says. It’s all about Trump’s plan to stop Iran. “Because we dislike Iran’s ayatollahs,” he explains matter-of-factly, “we are willing to starve Yemeni schoolchildren.”

Kristof’s accusation is one that must be taken seriously. Strategic concerns do not obviate moral imperatives. If the American government is killing innocent people in the name of geopolitics, the American people need to speak out.

***

The truth is that the US is not killing or maiming innocent people in Yemen. The US is supporting the elected government of Yemen as it tries to take back the country from a Shi’ite political sect called Ansar Allah (commonly called the “Houthis” after their founder Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi) that overran the capital and the northern part of the country in 2014.

The Islamic Republic of Iran supports Ansar Allah, which is similar in many ways to the Iranian-backed Hezbollah faction in Lebanon. Lest anyone be confused about its ideology, Ansar Allah has helpfully emblazoned its less-than-subtle manifesto on its flag:

God is greater

Death to America

Death to Israel

Damn the Jews

Victory to Islam

Why and how Ansar Allah took over the capital and forced the elected government to take refuge in south Yemen is too long of a story to tell here. Suffice it to say that Yemen is a torn country whose instability stems from deeply-rooted cultural differences that have caused numerous conflicts over the centuries and no less than five wars since the 1960s.

The Deep Map Explains Everything

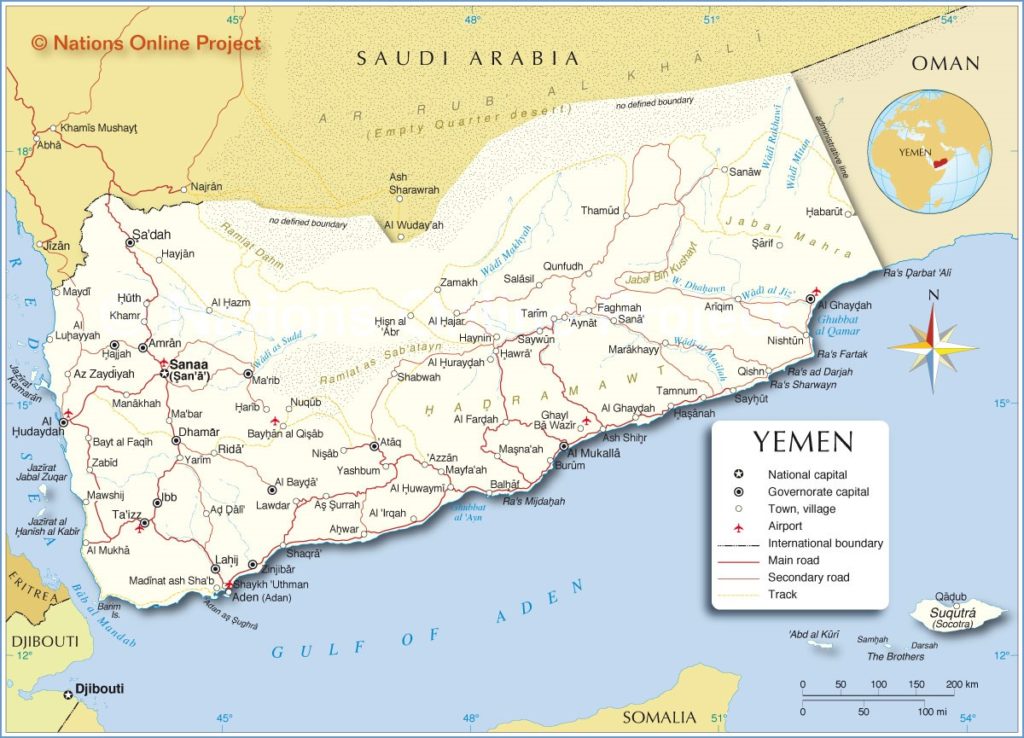

On paper Yemen looks like a pretty normal rectangular state:

Dig a little deeper and you’ll see that the political map doesn’t tell the whole story. The topographical map reveals a rugged country riven by mountains and desert:

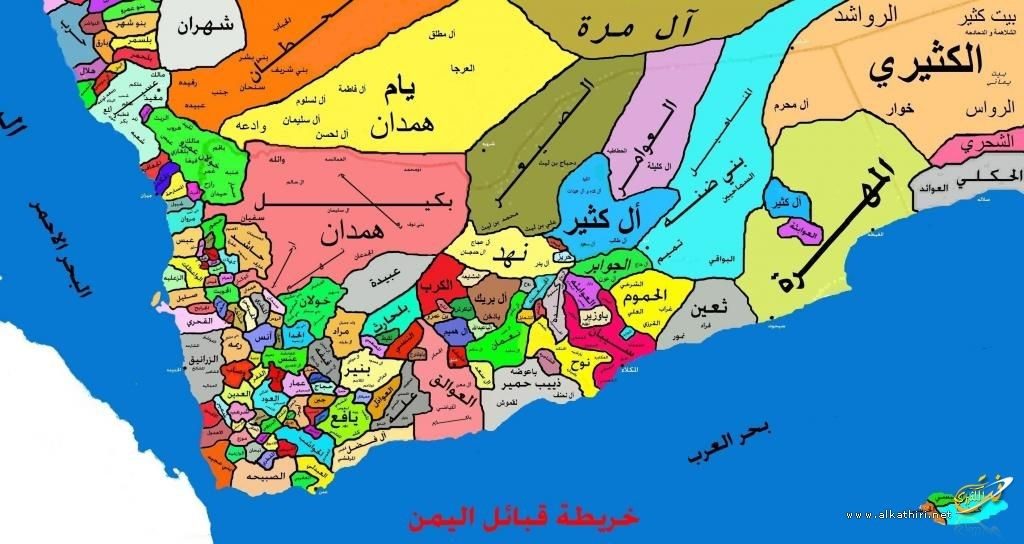

The tribal map exposes even deeper divisions:

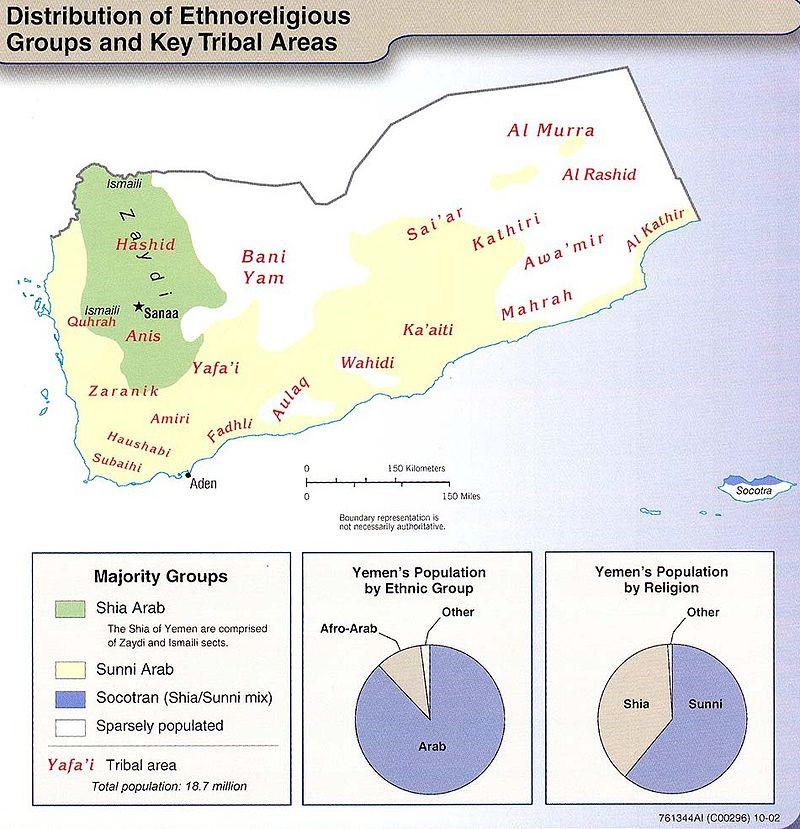

Superimpose on these maps the ethnoreligious map, which shows the long-persecuted Shi’ite (Zayidi) minority concentrated in the northwestern highlands, and you have all the ingredients for political instability:

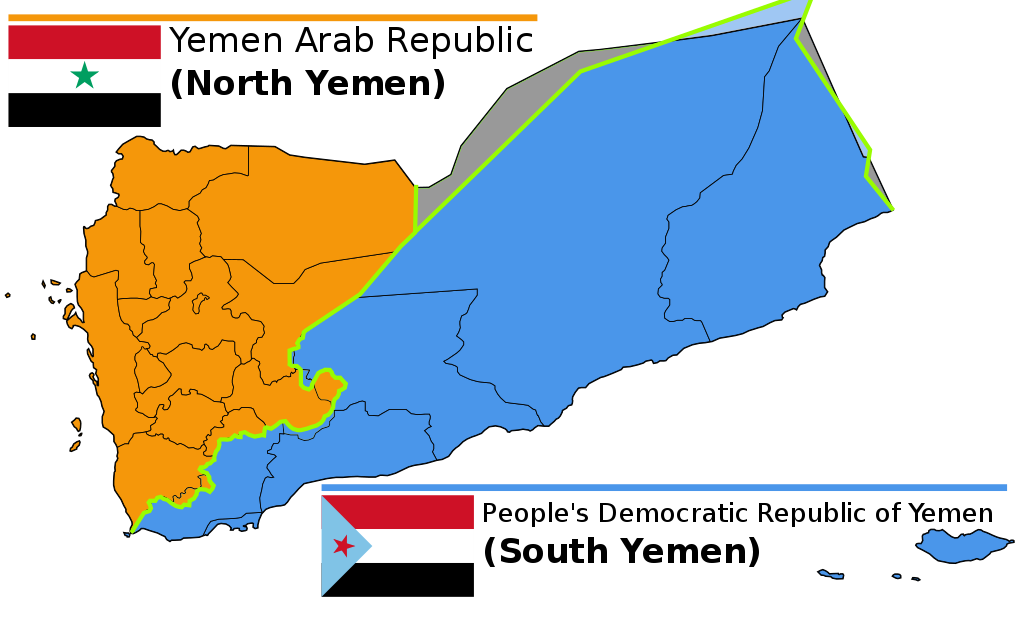

Given Yemen’s rugged terrain and many tribal and religious differences, it is no wonder that the territory has been a challenge for ruling powers since Ottoman times. It’s also no surprise that the area we now call the Republic of Yemen was ruled from the 1960s until 1990 by two rival states: the Yemen Arab Republic and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen.

The Two Yemens

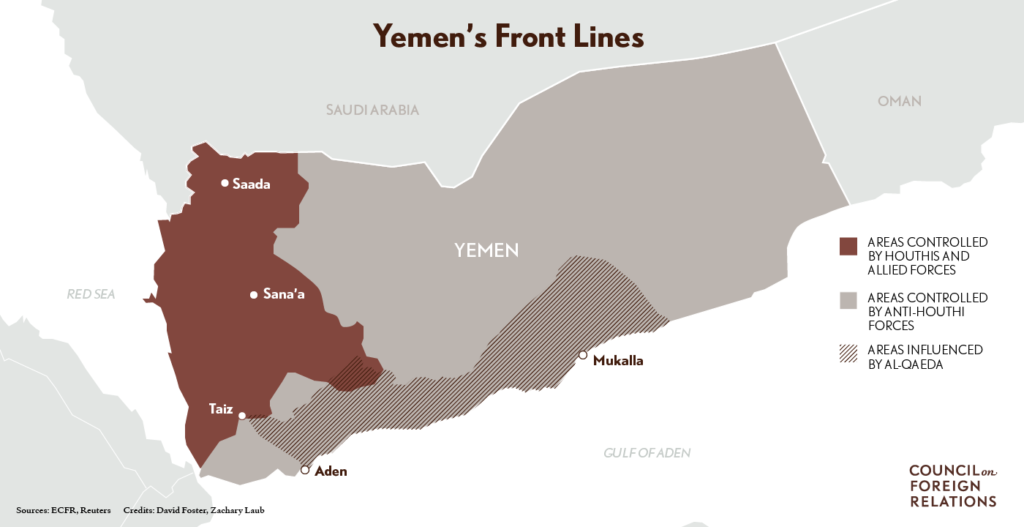

These two Yemens arose spontaneously from organic, underlying cultural realities. It’s easy to see the link between the demographic map and the political outlines of the two states. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union (the primary patron of South Yemen) in 1990, the two polities fused into a single state. It seemed like a perfectly reasonable idea at the time, even a case study in post-conflict reconciliation—but it was a major mistake. One glance at a map of the current civil war shows just how closely current events are tracking with the underlying realities.

These two Yemens arose spontaneously from organic, underlying cultural realities. It’s easy to see the link between the demographic map and the political outlines of the two states. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union (the primary patron of South Yemen) in 1990, the two polities fused into a single state. It seemed like a perfectly reasonable idea at the time, even a case study in post-conflict reconciliation—but it was a major mistake. One glance at a map of the current civil war shows just how closely current events are tracking with the underlying realities.

Yemen has remained in a constant state of civil war because Yemen is not a coherent state. It is the cobbled creation of elite politicians backed by Western diplomats who overlooked major cultural differences that led to further conflict and helped kill thousands of innocent people. The problem with Yemen isn’t that it’s divided, but that it’s unified—at least on paper.

Yemen has remained in a constant state of civil war because Yemen is not a coherent state. It is the cobbled creation of elite politicians backed by Western diplomats who overlooked major cultural differences that led to further conflict and helped kill thousands of innocent people. The problem with Yemen isn’t that it’s divided, but that it’s unified—at least on paper.

Next Steps for the US

The US has legitimate objectives in Yemen: Restoring an elected government that was unlawfully overthrown. Thwarting a violent Islamic sect that seeks to kill those who don’t abide by its theology. Countering Iran’s regional expansion. Preventing territorial safe havens for ISIS and al-Qaeda fighters who have profited from state collapse. All of these harmonize with our values and interests.

But Kristof and others are right to be concerned about the humanitarian toll. It is truly staggering. The US has sent almost a billion dollars in aid to Yemen since the beginning of 2017, but much more is needed. So long as we are playing a role in the war, even an indirect one, we must minimize human casualties and ensure that our military partners do the same. We have the leverage to reign in Saudi Arabia and the UAE; we must use it.

However, Kristof’s moralistic sermonizing and reductionism won’t do anything except aggravate partisan squabbling in the States. To say that Americans “are willing to starve Yemeni schoolchildren” because “we dislike Iran’s ayatollahs” is so simplistic as to be immoral in itself. That kind of sentimental, grade-school analysis of complex events gets us no closer to discerning a just course of action.

The real question here is whether the US should spend more time and money trying to re-unify a country that shouldn’t have been unified to begin with. Human societies have been evolving in Yemen since 5000 BC, and it’s hard to maintain that the 2014 political map is somehow the “right” one. It doesn’t reflect any underlying reality. It certainly isn’t sacred. The map has changed and will change again in the future.

Our diplomacy should work with cultural realities rather than struggle against them. Sometimes people just can’t get along. As the writer of Ecclesiastes aptly put it, “There is a time to tear and a time to mend.” Given the deep cultural differences between north and south Yemen—differences that have persisted over centuries and have not been moderated by nearly 30 years of unification—our greatest offense may be trying to mend what cannot be mended and spilling precious blood in the process.

—

Robert Nicholson is the executive director of the Philos Project and a co-editor of Providence.

Photo Credit: Aerial bombardment in Sanaa, Yemen, in March 2016, via Wikimedia Commons.