Imagine, if you will, a world full of completely unselfish people, of people who always thought of others first and not themselves; people who always sacrificed their own interests and looked for someone else to help. Paradise, right?

Wrong. Think again.

In a world like this, parents couldn’t really give each of their children a Christmas gift—something perfectly chosen for that child’s interests and developmental needs. As soon as they gave the gift, the child would look for another sibling to give it to. Pretty soon, the children would be passing all of their gifts around in a confusion of constant sharing, rather than going off to their rooms to practice for an hour on their new ukulele. By the next day, they would probably have given all their gifts away to the neighbor kids. Indeed, in this world, parents wouldn’t have given their kids gifts in the first place—come Christmas, they would’ve scanned the world for the neediest person they could find and given everything they could to that person instead. Or rather, they would have long since given away all their earthly possessions in a frenzy of selflessness (even as other equally selfless people tried to load them with new possessions).

Thankfully, even at our best, we are not nearly so unselfish a race as that. Indeed, the closest that any of us ever come is probably that awkward experience that ensues when two people reach a doorway at the same time and say, “no, after you,” for a few seconds until someone agrees to stop being noble and walk through—or perhaps when two friends spar over who’s going to take the check for a meal out.

John C. Calhoun proposes a thought experiment like this in the opening pages of his Disquisition on Government. He points out that, for most of us most of the time, our selfish sentiments are stronger than our benevolent sentiments—and that is actually a good thing for human society! When we extol someone’s “selflessness,” what we are really extolling is “less-selfish-ness,” the virtue of restraining one’s immediate selfish impulses enough of the time to make sure other’s interests are also well-served (a decision which is usually in one’s own longer-term best interests!).

While our runaway and usually shortsighted selfishness is a product of the Fall, Calhoun suggests that our propensity to think first of our own interests is actually a feature of human nature that we should praise God for: it is the only thing that renders our moral responsibilities manageable in a world of countless human needs—not to mention non-human goods we are called to protect. This self-interest extends, in somewhat diluted form, into a preferential treatment of our own families, our own communities and businesses, and ultimately our own nations. This preferential treatment enables us to immediately narrow down a potentially limitless list of possible goods that we could pursue, or problems we could address, into a handful of near and clear responsibilities. Much as I might want to end Third World hunger, I have to focus first on making sure my own children do not go hungry. And if I am governing a country, I will have to focus first on making sure my own nation does not go hungry.

Put this way, it is hard to imagine what might be wrong with an American politician calling for a policy of “America first.” Of course, it is true that the language of “me first” can often betray an attitude of “me only”—the kind of runaway and shortsighted selfishness that ignores the moral claims of others altogether. And it is also true that if I’m sitting on a billion-dollar gated estate surrounded by starving slums, the protest “I’ve got to look out for my own kids first” rings hollow; so too in the case of nations.

But the fact that national self-interest—what we call “patriotism”—can be abused does not mean it has no use. Indeed, it is no accident that the same hyper-liberal ideology that has turned its fire on the nation as a bastion of oppressive particularism also seeks to deconstruct the family on similar grounds. We hear often today about how we live in “a global society” and have to take up the responsibilities of “global citizenship.” But what these exhortations miss is that the exponential growth in human knowledge over the past century has not been matched by nearly as rapid growth in human agency. It is now possible for a housewife in Tennessee to be aware of a rape in Bangladesh within hours or minutes, but she is only marginally more able to do anything about it now than she was 100 years ago.

The result of this rapid expansion in our moral horizons, together with a sustained ideological assault on the concentric spheres of responsibility that used to help order our moral concern and sense of duty, is a sometimes almost paralyzing anxiety. We are constantly barraged, through a deluge of information technology, with news of perils facing our climate, our military allies abroad, political dissidents in Saudi Arabia, religious minorities in Russia, or struggling farmers in South Africa. And we are encouraged to think of all these problems—and especially the problems of those most unlike us—as our own problems. And in some measure, they are; nihil humani alienum a me puto, everyone created in the image of God ought to be able to say. Moral apathy is a real danger; one that we must always combat. But on the opposite end, anxiety can be equally paralyzing.

It is precisely in order to anchor our moral horizons at the balancing point between apathy and anxiety that we need the nation and a sense of patriotism. Our nation, assuming it represents a meaningful community of interest with an intelligible narrative and tradition—as I would argue that America does—serves as precisely the sort of extended zone of self-interest that is necessary to give clarity and priority to our duties and responsibilities. It provides a starting point for our engagement in world affairs in the same way that the family provides a starting point for our engagement in our local community. But the nation—especially our American nation—is also large enough and diverse enough that it provides no want of opportunities to expand our moral horizons to encompass the needs of those quite unlike us.

Indeed, it is ironic that the same people who have most loudly demanded our solidarity for marginalized groups within America itself have at the same time attacked the whole concept of “America first” or of the value of the nation. If our limited powers of empathy are to be stretched ever-thinner across a limitless horizon of global concern, there will be little enough of them left to forge ties of mutual love and loyalty with the rich diversity of fellow Americans. With the threads of imagination that tie the rich tapestry of America together fast fraying, it is high time to take a step back from ideological globalism and remember the value of patriotism.

—

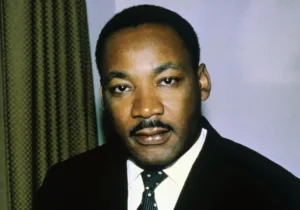

Photo Credit: Delegates hold “Make America First Again” posters on the Republican National Convention floor in Cleveland, Ohio, on July 20, 2016. By Ali Shaker for Voice of America, via Wikimedia Commons.