Three South American countries—Bolivia, Chile, and Ecuador—have experienced massive protests in the past couple of months. Discontent against the powers-that-be originated for different reasons, including anger over subsidy cuts, costlier living expenses, disrespect for indigenous rights, and one head of state’s attempt to remain in power.

In all three countries, their respective governments have blamed external actors for the violence. While a case can be made for this possibility, blaming “others” is also a sign that these presidents (or the former president, in the case of Bolivia) did not want to admit their own faults and shortcomings.

The Protests

The first wave of unrest occurred in Ecuador when President Lenín Moreno decided to cut oil subsidies via Decree 883. Salary reductions for temporary public sector jobs and less vacation time for government employees have also been unpopular. These measures prompted unrest from the middle and lower socioeconomic classes, while indigenous movements have joined the protests, weary that the government’s neoliberal economic policies could affect their homelands. At the height of the unrest, President Moreno and his government fled Quito and relocated temporarily in Guayaquil. The situation generally calmed down after President Moreno canceled his order to end the subsidies, though the population remains vigilant and distrustful.

Then came Chile, where President Sebastián Piñera ordered an increase in public transportation prices. Chile is a member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and is generally regarded as one of the most, if not the most, advanced economies in Latin America. However, the South American nation has the most socioeconomic inequality among all OECD countries, as higher costs of living have not been matched by better salaries. President Piñera canceled the price hike, changed his ministerial cabinet, and recently called for a referendum to rewrite the Chilean constitution. But protests and violence continue. Many protesters have been killed, and even more have been left blind after police shot them with pellet guns, though most protests have been peaceful. Of course, some vandalism has damaged parts of the public transportation system, historical monuments, and buildings. Some protesters even attacked an army base.

Finally, former President Evo Morales claimed victory in Bolivia’s October 20 elections. He ruled from 2006 and 2019 and was an anomaly amongst Bolivian heads of state precisely because he ruled for so long. Bolivian presidents do not usually stay in office for a full presidential term. For example, between 2002 and 2006, the country had four head of states.

Morales was generally popular, but he seemed to have developed an appetite for power, as he called for a referendum in 2016 to run for another unconstitutional term. Even though the population voted against it, he ran anyways. There has been widespread controversy about whether some kind of foul play occurred, as the electoral commissioned stopped reporting the vote count results on election night when Morales’ main opponent, former President Carlos Mesa, was closing in. By the time the commission resumed reporting the results, Morales was solidly in the lead and proclaimed victory.

Protests and violence ensued, and Morales went from declaring victory, to calling for new elections, to eventually leaving the country and seeking asylum in Mexico. His vice president and ministerial cabinet resigned, and following the constitution, the interim president of Bolivia is now Senator Jeanine Áñez. She has called for new elections, though an exact date has not been given yet.

Who Is to Blame?

As previously mentioned, one common denominator amongst these three cases is the accusation of external influence. In the case of Ecuador, President Moreno blamed former President Rafael Correa and the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela. “They are the ones that are behind this attempted coup, and they are using…the indigenous population,” he stated. Similarly, President Piñera stated, “We are fighting against a powerful enemy.” Meanwhile, interim President Juan Guaidó of Venezuela has blamed Maduro, too: “Maduro…has the capacity to finance, via gold extracted from mines, different groups that can infiltrate and foment violence and destabilize the region, but he will not succeed.”

On the other hand, former President Morales described his fall from power as a coup. In a November 13 tweet, he stated that “the coup d’etat that has provoked the deaths of my Bolivian brothers is a political and economic conspiracy that was planned by the US.” Morales is no friend of the US, as he kicked out the US ambassador to Bolivia, Philip Goldberg, in 2008, and has approached nations like Cuba, Iran, Russia, and Venezuela.

Who you believe depends on your beliefs and ideology, and who you regard as “the enemy.”

Blaming “others” for the violence in these three countries, regardless of each government’s political ideology, is an easy way for these leaders to avoid taking any blame for their actions. After all, the abrupt end of oil subsidies, increasing cost of life, and destruction of the natural environment (where indigenous communities live) are valid reasons for the citizens of Chile and Ecuador to be angry. Similarly, Evo Morales’s desire to remain in power, ignoring a referendum, and (allegedly) tampering with the vote in October took Bolivians over the edge. This does not excuse the destruction or deaths since then, but the violence did not occur in some vacuum of anarchy.

Conclusions

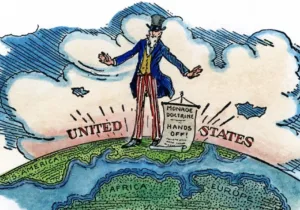

It may very well be the case that there was some type of foreign influence in the violence in Bolivia, Chile, or Ecuador. After all, this is South America, where foreign interference in domestic affairs is part of the region’s history.

With that said, as one Chilean citizen stated, “we want dignity.” When governments blame outside actors as instigators of violence, they minimize the protesters’ valid grief and demands. The populations of these three countries are making their opinions and wishes clear, and La Paz, Quito, and Santiago should, first and foremost, look into their own actions and issue a mea culpa, rather than blame others.