Today is Maundy Thursday, the day faithful Christians memorialize the several events surrounding Christ’s final Passover meal, which he observed in the company of his closest friends—well, in the company of mostly his closest friends. This evening initiates the Paschal Triduum, the three-day sequence commemorating the passion, crucifixion, death, burial, and resurrection. “Maundy” derives from the Latin mandatum, for mandate or commandment, commemorating, primarily, the “new command” that his disciples love one another as he has loved them. This and similar charges Jesus issues instructing his disciples to follow his example peppers this final evening. We see this when he washes his disciples’ feet and demands they do likewise, when he says he is about to go where they will later follow, when he says that whoever loves him will obey his commands, living as he has lived, and when he instructs that they are to eat the bread and drink the wine in remembrance of him.

The bread and the wine are a natural point of focus. They are grim symbols for the blood and flesh split and spilt so that those who love him might be reconciled with God. This suggestion of a sacral dimension to death is nothing new. In God’s Gamble: The Gravitational Power of Crucified Love, Catholic writer Gil Baillie points to the ancient origins of ritual victim sacrifice for the sake of the common good. Such sacred violence usually followed a corresponding pair of gestures. First, someone somewhere reached out to acquire some good thing. Someone else saw this acquisitive gesture and was struck with envy, a sudden desire for the very thing the other desired. Human beings do this all the time. Baillie asks us to imagine a child in a room full of toys. Choosing among the various things, he begins to play with a stuffed bunny. Soon after, another child enters the room. Looking around for something to play with, he notices the first child’s interests. What toy, Baillie invites us to guess, is the new arrival going to want to play with? Now let’s imagine the new boy, being decent, doesn’t just walk right over and try and take the bunny. Instead, he feigns interest in something else, but keeps a watchful eye out on the boy and the bunny. Eventually, having grown bored with it, the first child sets the bunny aside and reaches for something else. The second one now moves in and snatches up much-desired bunny. In all likelihood the first child will demand it back, insisting he had it first. Such rivaling desires, if left unconstrained, can can boil over into real conflict. As Virgil instructs Dante:

For when your longings center on things such

that sharing them apportions less to each,

then envy stirs the bellows of your sighs.

It is no different at the societal level. As two rival wills vie for a given thing—be it material or immaterial—other observers will themselves be drawn in, suddenly infatuated with something they might never have known they wanted. Eventually, the competition itself takes over and the desired thing, long forgotten, gives way to an undifferentiated brawl over nothing. Human beings long ago recognized that cultural procedures had to be adopted in order to attend to these conflicting passions lest everything dissolves into a war of all against all. Social cohesion—community survival—depends on the discovery of a release valve. It’s at this point that a second gesture is made—an accusatory one. Someone, or some group, is accused of being responsible for all the conflict and offered up as the scapegoat. The motion made, it is seconded, and the affirmations continue until there is found the stability of a near-consensus—as Baillie puts it, a unanimity minus one. The victim’ or victims’ fate thus sealed, the violence that follows—the extirpation of guilty—is cathartic. The communal crisis is averted. Civilization has bought itself more time. Until the cycle percolates afresh.

Such pageants of ritualized violence are not limited to that age when all the nations had many gods. Though I—and Neil Gaiman—might suppose it’s an open question whether that age ever really ended. A Joshua Mitchell Providence essay written in the midst of 2020’s summer race riots explores the American admixture of pagan and Christian logic. Americans, he rightly asserts, are torn between competing understandings of justice. Do we regress to pagan conceptions of justice and their demands for blood retribution through carefully prescribed modes of choreographed catharsis; or do we reinvest in an idea of justice grounded in a Christian conception of persons, which recognizes that justice requires something more than cathartic rage, however efficacious—or titillating—the rage might be in the moment?

This desire for justice is deeply human, and the character of justice is such that even that desire for that kind of justice that can only come through violence—or better, force-—is not necessarily misplaced. One component of retributive justice is the proper obligation to give to each their due. Holding one another to account is to honor each other as agential beings and to acknowledge that choices matter. Pronouncements of guilt can be a grace—articulating aloud the perception that the alleged guilty-party has erred. If the judgment is true, it might work in the heart of the accused, forcing them to confront what they have done and possibly bringing them to repentance. Such justice also acknowledges the victim. To requite injustice is one mode of vindicating its victims—including both the direct victim and those who suffer alongside the victim. The administration of justice is not often a simple procedure. Mitigating circumstances matter, including the marbling of one’s personal history—much of which is not always their fault—and their will and the effect each then play in affecting what they do. A part of what might be due to one another, then, is mercy; the application of which is no less complex than that of justice itself. Especially because mercy always costs someone something—and it’s a very hard thing when this cost, or a portion of it, is expected to be borne by the victim.

This yearning for justice is beautifully—if tragically—illustrated in Kenneth Branagh’s Murder on the Orient Express. A little girl has been kidnapped and murdered and the human monster that did it has gotten away with the crime. Until now. He is tracked down by an assembly of the little girl’s loved ones—family members, friends, and other relations whose lives were in various and terrible ways, direct and indirect, disfigured by the murder. They successfully execute a meticulously orchestrated plan to kill the murderer and avenge the child. Judging whether their act is murderous bloodlust or justice is a part of the film’s preoccupation. Also in play is the correlation of the murderer’s killing with ritualized violence. Twelve of the little girl’s loved ones take part—like a jury—in his execution, each taking turns stabbing him. The scene is extraordinarily rendered, and its careful choreography brings to mind the Great Sacrament. The killers share the same knife, stabbing their monstrous victim and passing the weapon between them, one by one. It is—to my mind clearly—a eucharistic image. As each delivers their individual strike, plunging the knife into the soft body of the accused, many of their faces are transfigured: evident grief is at once both amplified and joined by expressions of triumph, rage, and even ecstasy. In a word, they experience catharsis. It is, of course, deeply flawed; they are broken people struggling for justice in broken ways.

The eucharistic imagery is confirmed the next time we see the twelve all assembled together again. In the climatic scene, where the great detective Hercules Poirot will pass judgment, they are all sitting together at a single table, arranged in such a way as to unmistakably evoke Leonardo’s Last Supper. It’s jolting. You don’t even have to take my word for the connection, for it turns out that Branagh confesses it in his director’s commentary. He had seen the painting on a recent trip and thought it would fit for the story he was telling. The tragedy of the whole affair is that the retribution is freshly accomplished and yet, already, the twelve recognize its terrible imperfection. Human justice is only ever a feeble shadow of Divine Justice. It is only ever approximate. And, like mercy, it too sometimes has costs borne by the victims.

This cost is perhaps partly what is at play in King David’s dashed hope of building the Temple. 1st Chronicles tells us that David is refused the privilege of constructing a Temple for the Lord because he is a man who has shed much blood and fought many wars. Instead, his son Solomon, who will be a man of peace, will build it in his stead. This seems terribly unfair. For starters, most of the blood that David has shed has been done in God’s service, fighting wars God had him fight. Moreover, the peace his son enjoyed was the fruit of those wars. Even more, much of the material—the gold, silver, bronze, timber, and rock—that will be used to construct the Temple include the loot of warfare. What gives? The Book of Numbers tells us that a soldier who has shed blood must stay outside the camp for seven days. But this does not mean the soldier is guilty—for even a menstruating woman is barred from the camp. It only means that he is, in sometimes opaque ways, they, having touched death, are not presently fit for community life. Is this the judgment on David? The violence that David deployed, the blood he shed, carried a cost—even if it was morally right to do it.

My own work on moral injury, especially through conversations with warfighters, tells me enough to know that killing leaves an indelible mark. As the eponymous gunfighter puts it in Shane—and as taken up in its successor Western Logan, “There’s no going back from the killing. Right or wrong, it’s a brand, and the brand sticks.” Keeping to cinematic and literary allusions, one thinks here of Frodo at the Grey Havens. “I tried to save the Shire,” he says to Samwise. “And it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so Sam, when things are in danger someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.”

The just war tradition accepts this. Never feigning to be a source of moral catharsis or perfect justice, and while deeply Hebraic, it is not a religious scheme for utilizing violence to save the world or purge it of guilt. It is simply a mechanism to prompt and limit force to bring about approximations of justice that, however partial and imperfect, are, in the face of sufficiently grave evil, the only thing with a realistic chance at keeping the beasts at bay and setting up the conditions that make peaceable life possible.

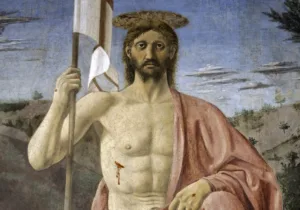

We see in the ritual of the crucifixion the same human exertions to harness violence as time-proved means to purge guilt. But, this time, the scapegoat mechanism—curiously modifying the description it mirrors found in Leviticus 16—does not work. Jesus threw a stick in the spokes of the sacrificial system. Now, the truth about the scapegoating mechanism—about sacrifice and sacred violence—is revealed. Christ as scapegoat was supposed to rid the community of its sin but, instead, it made their sin more clear to them. And now they knew they needed another way to deal with it. The ritual failed to eventuate in the required catharsis, for the death of the utterly innocent victim is proved a false and debilitating remedy. The onlookers stumbled away beating their breasts. This was not an act of contrition, but a recognition of their utter failure and subsequent hopelessness. Never again would a scapegoat effectively mollify the longing for absolution.

When Jesus takes up the cup and the bread and passes them along the table, he institutes the first eucharist. No one else knows it yet. But they register the new commands—that they too are to love one another as he has loved them, that they are to wash one another’s feet as he has done. The human tendency to mirror and model our behavior off another’s, our appetitive drive to long for what others long for so that envy turns to conflict is, in this moment, given its true purpose. We were made to imitate Christ. We were made to be Sons and Daughters of God—to be perfect as He is perfect.

As Virgil says to Dante in the lines immediately following the quote above:

But if the love within the Highest Sphere

should turn your longings heavenward, the fear

inhabiting your breast would disappear;

For there, the more there are who would say “ours,”

so much the greater is the good possessed by each

This longing to imitate, the imitatio christi reveals, is not, when properly manifest, a diminution of human freedom, but its fulfillment. To return again to Baillie, human flourishing finds its objective measure in “how well we have replicated in our lives the pattern, the Logos.” Our efforts to do so yields the intrinsic meaning of our existence. Golgotha is God’s final appeal. There Christ makes his final case for love, forgiveness, and mercy.

It is just and mete for ecumenical purposes, if no other, to understand the Christian faith as a religion of the Book. But Christianity is not ultimately a set of rules, ideas, or doctrines. Christianity is about a Person, three-tiered, and the yearning humanity has to commune—to be in communion—with that three-tiered Person. Again, the eucharistic imagery abounds.

The wine and the bread—the blood and the flesh—of the Last Supper, and the consequent events of the unfolding Triduum which follows from it, reveal that violence has a necessary place in a world in which we long for peace but in which the enemies of peace have not surrendered their say. This is not to make holy war out of just war. Human warfare has nothing directly to do with reconciling sinners to God, or promoting faith. Nor does the just warrior suggest that he stands opposed to his enemy as the simply righteous against the simply unrighteous. But it is to suggest that works of justice and mercy always share a similar and terrible moral logic. Included among the characteristics that follow is that violence must only ever be deployed with the intention of winning peace—or its partial approximation in limited circumstances. Retribution, protection, the vindication of victims, reconciliation with the enemy, are all component parts of this approximation and have a role to play. Peace, therefore, mustn’t be understood as a virtue, per se. It is the fruit of virtue.

Meanwhile, the love that we are, ourselves, supposed to mimic to one another is the love of a man who we have seen—all week—is a man of peace but no pacifist. In a world in which some neighbors are hell-bent on devouring other neighbors, it ought to be those nourished in the Hebraic tradition who are the first to stand between the aggressor and his victims—even if, in the last resort, violence must be deployed to resist and to rescue. War and violence and harsh justice must sometimes be. But only for the sake of love and the goal of peace and of setting up the conditions that give these great goods a chance.

Keeping faith with Christ in this effort, however modest, is our only business. The rest is not up to us.