Famously infamous for his collection of dictums, Donald Rumsfeld’s first rule for government service mandates that “public servants are there to serve the American people and our nation.” This is immediately followed by the directive: “Serve them well!” A few years back, Rumsfeld mused that his own life had run for more than one-third of the life of the nation—most of it spent in just such well-serving service. That extraordinary run ebbed to its conclusion on Tuesday night, just a handful of days shy of his 89th birthday.

Over the course of that near nine decades, Rumsfeld was a naval aviator, congressman, White House Chief of Staff, U.S. Ambassador, Cabinet officer, special presidential envoy, secretary of defense—he is the only one to have been SECDEF twice, his first stint as the youngest ever and during his second tenure the oldest as well, a distinction he held before the installation of Leon Panetta bumped him back to younger man status. He was a chief executive officer, corporate board member, philanthropist, and husband, father, and grandfather. He was, as has been said elsewhere of another, a man, take him for all in all. And, indeed, it is not unreasonable to think we shall not look upon his like again.

This will be welcomed news to many. In the wake of his death, the cruel and the base and the heartless have emerged from their dark places to revel in Rumsfeld’s death like vile little munchkins. Actually, not like the munchkins. The munchkins can be excused because they celebrated the death of the Wicked Witch of the East. We needn’t belabor what ought to be the obvious distinctions here, but it is worth a brief segue to tackle a secondary issue. Even if Rumsfeld’s more vicious detractors pegged him rightly, we have it on good authority that we ought not to rejoice even in the death of the wicked. To be sure, this mandate can be hard. Some—think a Hitler, a Pol Pot, a Stalin, or a Wicked Witch—were so intentionally devoted to such indiscriminate and disproportionate evil that their deaths seem a net profit for the world. But even regarding monsters such as these, people of good will should still register a difference between gratitude that a history of evildoing has finally come to an end and the ugly glee that rejoices in that death per se. The munchkins, for all their properly felt relief, should nevertheless realize the tragedy that someone else has so misspent their lives that their death is not a cause of grief. This is a tension that can be held.

But all of this is quite beside the point. Those who celebrate the death of Donald Rumsfeld as the death of a monster are fools. If they are simply ignorant, then they can be forgiven for being merely stupid fools. But most appear to be reasonably sentient human beings who ought to know better, leaving us to assume they are culpable in only seeing what they want to see. Their small-minded and heartless insistence on gloating at public announcements of Rumsfeld’s death and on posting nasty little things on his family’s social media pages display astounding indecency. Their behavior is no longer surprising, but it still manages to shock the hell out of me. It is pathetic and sad. Shame on them.

This isn’t to say the Secretary was perfect. Of course, he wasn’t. He himself was often ready to speak and write of the “mistakes, miscalculations, and disappointments” that sometimes occurred over the course of his service. Some who knew him best are perfectly willing to offer fair-minded evaluation of his professional life and personal character. But many of the mistakes with which he is most associated—the invasion of Iraq, the push for regime change, the bad intelligence regarding weapons of mass destruction, listening to—or not listening to—his generals were collective errors not of his own sole doing. Others—the level of troops allotted for the invasion for example—were more rightly associated with him alone. But these mistakes—even where grounded in personal shortcomings and even when of disastrous consequence—cannot reasonably be attributed to malice. Character is complex. It’s often most fruitful to evaluate character in the wake of personal hardship. Consider the relative grace with which, in 2006, Rumsfeld seemed to accept onto his own shoulders the whole of the weight of the Bush administration’s failures in Iraq, bearing alone into exile what was really shared guilt and blame. When he left the administration and was pilloried by the talking heads, few of his colleagues publicly defended him. Those who knew him well have spoken about how much this hurt him, even if those who knew him less well would never know it. I never saw him complain or be defensive. This is to stress the point that Rumsfeld didn’t appear to behave as his detractors should have expected him to if they were correct in their evaluations of him. Perhaps all this speaks to even his detractors’ recognition of his extraordinary capacities—they seem to think he was responsible for everything. In any case, the speed with which many moved from adoring praise to unbridled censure of him, calls to mind another of Rumsfeld’s favorite rules, this one borrowed from Harry Truman: “If you want to have a friend in Washington, DC, buy a dog.” Rumsfeld, characteristically, added his own corollary: “If you do, get a small dog, because it may turn on you.” Doggone right.

Even from my limited vantage point, however, it clearly isn’t fair to leave the impression that his true friends turned on him. When Rumsfeld settled into retirement with his wife, he and Joyce set up an enterprise to continue their lives of service. The Rumsfeld Foundation is grounded in their gratitude for the opportunities that free political and economic systems provide for individuals. Understanding the vital importance of strong leaders in helping such systems flourish, the Foundation promotes programs that encourage moral leadership development and public service at home and abroad with focuses on supporting graduate work, military veterans and their families, and the development of freer societies in Greater Central Asia. For the last seven or so years, I have been greatly honored to be a part of the Foundation’s Graduate Fellows Program. An impressive collection of rising and established leaders in public service posts from intelligence analysts to academic professionals, the network is encouraged and developed through a catalogue of activities including speaker series, weekend retreats, workshops, and conferences. A notable array of military, political, national security, and diplomatic leaders fuel the network. They are drawn by their devotion to Rumsfeld. On numerous occasions, in both public and private conversations, they have candidly testified to their deep respect for the Secretary, his service to the nation, his love of country, and his deep care for the men and women who stand on freedom’s wall. If character can be confirmed by the quality of one’s friendships, then the virtue of Rumsfeld’s character is firmly established. I would weigh the value of his cohort of admirers as highly as that of anyone else I know.

Reflecting ack over the years that I got to know the Secretary—however modestly—two anecdotes stand out as I consider the kind of person he was. The first comes from the morning of September 11th, 2001. Secretary Rumsfeld was in the Pentagon, sitting around a wooden table that had once belonged to Union Army General Tecumseh Sherman. He and his team were absorbing the news of the attacks in New York City when the Pentagon itself shuddered and shook. Looking back on that moment, Rumsfeld said, “Sherman had famously commented that ‘war is hell.’” And “hell had just descended on the Pentagon.”

You can tell a lot about a man by the direction he runs. Rumsfeld raced through smoke and jet fuel fumes toward the crash site. Making his way outside he found “fresh air and a chaotic scene.” He wrote:

Hundreds of pieces of metal were scattered across the grass in front of the building. Clouds of debris, flames, and ash rose from a blackened gash. People were scrambling away from the building, refugees from an inferno that was consuming their colleagues.

It had only been a few minutes since the attack and first responders were not yet on the scene. “A few folks from the Pentagon,” Rumsfeld recalled, “were doing what they could do assist the wounded. I saw some in uniform running back into the burning building, hoping to bring more of the injured out.” Rumsfeld pitched in. There’s a famous image of him, helping to carry a stretcher. It sounds about everything that needs to be said.

As more people arrived onsite to assist, the Secretary began to make his way back to his office to gather the information he needed to do his own job. On the way, he picked up a small, twisted piece of metal from the airliner that had hit the building. “That piece of the aircraft has served me as a reminder,” Rumsfeld wrote, “of the day our building became a battleground—of the loss of life, of our country’s vulnerability to terrorists, and of our duty to try and prevent more attacks of that kind.” Rumsfeld shared similar words with me as he showed me that twisted piece of metal, on display in his office in Washington.

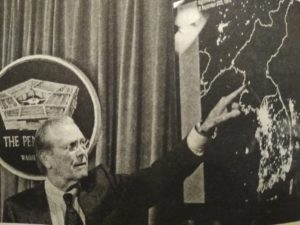

The second image I carry with me conveys Rumsfeld’s undiluted love of America. Unlike too many, he never believed in the crass and fashionable idea that America was what was wrong with the world. He believed America to be a nation of hope, possibility, and opportunity—a model for millions around the world. “The American people,” he mused, “have done more for more people around the world than perhaps any other country in history.” He also believed deeply in our free system of government and our free economy. “The proof,” he insisted, “is there.” For many years, Rumsfeld kept close at hand a photo that he believed said it all. It’s satellite photo of the Korean peninsula taken at night. The image shows literally millions of lights all across the Republic of Korea—visible evidence, he insisted, of the “energy, vitality, and industriousness unleashed by their free market economy.” In contrast, the totalitarian, communist north above the demilitarized zone, was essentially in total darkness—only a pinprick of light, at the capital Pyongyang, offered even a modicum of relief from the stark blackness. Of this, Rumsfeld pondered:

Consider that the same people live in the north as in the south. There are the same resources available to the north and south, and the same heritage and culture north and south. Yet the outcomes are dramatically different…South Korea has succeeded and succeeded brilliantly because individuals and entrepreneurs have the freedom to pursue their self-interest—to invest, create jobs, take risks, make mistakes, fail, try again, and achieve.

The image is a powerful visual lesson “of what works and what does not work.”

Taken together, these images say much about the man. Taken together, they also helped inform his love of America and the endless promise of the American people:

Before these United States, no nation on earth had a practice of selecting as our leaders individuals who were not blue bloods or part of a genealogical lineage or necessarily even among the elite. Our constitution was draft by farmers, and writers, and tradesmen, people rich and poor, from north and south. We’ve made mistakes, we’ve been counted out, but we have preserved and our people have prospered. America will always be a beacon of hope to the world as long as there are young men and women capable and willing to lead. I have every confidence they are out there. And I have every confidence that when the time comes they will rise to the challenge of their generation.

Donald Rumsfeld knew these leaders won’t perform perfectly. “Sometimes,” he wrote, “they’ll fall flat on their faces.” The important thing, however, is “that they’ll get up again.” The world, to parse another Rumsfeld rule, is run by those who show up. Rumsfeld showed up again and again and again. Harry Truman, Rumsfeld recalled, used to talk about an epitaph he saw on a tombstone in Arizona: “Here lies Jack Williams. He done his damnedest.” Rumsfeld was content know that he was not, himself, all that important. But he knew his responsibilities were. And if in the face of them he could look back and say pretty much the same thing about himself as what said of ol’ Jack Williams, then he would have done enough.

Job done, Mr. Secretary. Fair winds and following seas.