“Can the People Act?” by Henry P. Van Dusen

January 20, 1947

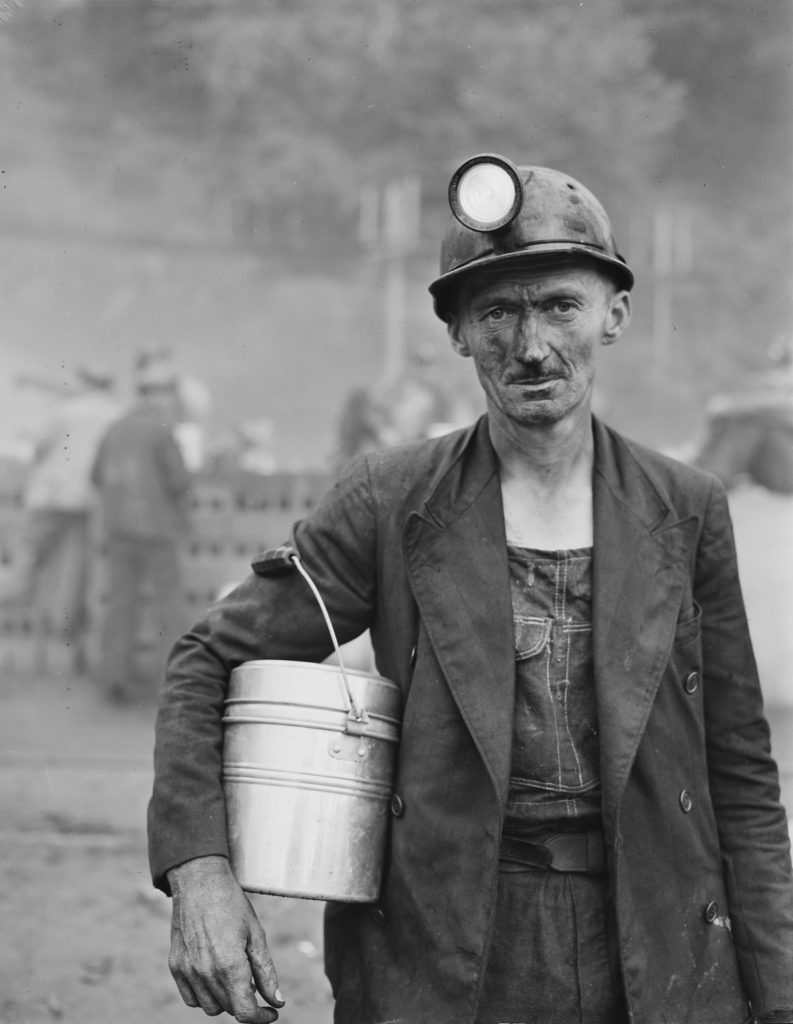

Twice in recent weeks, paralysis has gripped a vital organ of the American economy through the action of groups sufficiently powerful and determined to induce paralysis. Twice, the American people have found themselves powerless to forestall peril to the health if not the life of the entire nation. Each time, their government has presented the sorry spectacle of virtual impotence to protect the general welfare against organized and resolute special interests. The eventual cancellation of the coal strike affords small comfort; as Professor Pope pointed out in a recent issue of Christianity and Crisis, it must be recognized as a postponement rather than a solution of the basic issues. Thus is brought to clear focus probably the gravest domestic threat to American democracy in the uncertain years ahead—servitude of the citizenry as a whole to intimidation and dictation by massed power.

In principle, the meat stoppage and the coal stoppage stand on a par. True, the latter embodied greater danger to the national organism. But the ends sought and the methods employed were identical. The united meat packers’ strike in November and the United Mine Workers’ strike in December confront the American people with the same fundamental issue.

To be sure, the problem is not new. The first Roosevelt crusaded gleefully against “special interests.” The urgency of the problem in our day lies not in its novelty but in its magnitude. Methods to secure minority ends against majority weal, originally developed by organized business and finance, are now employed by every segment of the population with limited and particular interests—labor, farmers, races—until the jibe that Washington is degenerating into “government by pressure groups” is only an overstatement of truth.

Nor does it suffice to recognize that the present impotence of the general public is just retribution for earlier failure to assure legitimate rewards and safeguards for formerly exploited elements, notably farmers and industrial workers. The righting of past wrongs has now advanced to a situation which not merely periodically threatens the physical health of all the people; it chronically imperils the healthful functioning of the national organism itself.

The ominous fact is: the bedrock of American democracy, vaguely yet adequately identified as the middle and professional classes, is rapidly losing effective voice in the affairs of state. It is not too much to say that upon these elements of the population the Republic has been reared, that more than any other elements they retain understanding of and loyalty to the true genius of the nation, and that, whether through their own distinctive virtues or merely through self-interest, they still represent the interest of the nation as a whole. Their plight has received vivid demonstration in recent months, not in particular struggles over meat or coal, but in their impotence to halt the larger drift of post-war economy in which, by and large, capital and labor have made common cause—the cancellation of all controls with the inevitable results of skyrocketing prices, perilous inflation and the liquidation of the value of fixed incomes, modest savings and prudent thrift which are the virtues and protections of our most solid and substantial citizenry. The vicious incidence falls not only on worthy individuals, it falls first and most fatally upon the great institutions of public welfare—churches, hospitals, education, philanthropy—and then upon those who have created these institutions and who support their continuance. Their real interest, which is also the “general interest,” is not identity with the limited objectives of one or another pressure group, but a common defense against the dictation of them all. A reliable Gallup Poll of attitudes toward organized capital, organized labor, organized farmers, and the rest would probably show the great majority of Americans returning a resounding and resentful protest: “a plague on all your houses.” But that protest is wellnigh impotent.

Here is the basic truth: the logic of developments through the past half century has effected not only the progressive stripping of these elements of effective influence upon national policy, but even their progressive elimination from the national population. It may be questioned whether representative democracy can long continue without the power of these elements to arbitrate between and decide against special interests of whatever kind. The great question for the future of our nation is: can the will of those who represent the general interest over every particular interest be made effective in American life?

In a country already overridden with organizations, one hesitates to suggest the creation of another. But one is tempted to wish that leadership of sufficient vision and ability might arise to bring to birth just one more organization. It might bear the simple title “CITIZENS INCORPORATED.” It would be committed to a single principle—the interest of the whole people above the interest of any segment. It would espouse a single objective—insistence upon the general welfare against every threat from a special and limited dictation.

In this situation, what, if any, is the role of the churches? Certainly not to organize CITIZENS INCORPORATED. Certainly not to function as one more “pressure group,” even in defense of the common interest. It is a fact, however, that the active membership of the churches whom they may hope to guide is drawn predominantly from precisely those elements in the population which we may call “the general public,” those individuals and groups whose self-interest on the whole coincides with the general welfare. It is a legitimate role of the churches, indeed an inescapable responsibility, to bring their constituencies to intelligent understanding of this issue which lies at the root of most of our domestic maladies, and of the dimensions of the peril. In the long view, the survival of American democracy in the troublous decades ahead may hang on a resolution of this problem.

Henry P. Van Dusen (1897–1975) served as Union Theological Seminary’s president from 1945 until his retirement in 1963. For his leadership in the ecumenical movement, his portrait appeared on the cover of Time in 1954.

“Deeper Issues in the Coal Strike,” by Liston Pope

December 23, 1946

The capitulation of John L. Lewis represented a postponement rather than a solution of the basic issues involved in the coal strike. But such respite an economy that was rapidly being brought to its knees may be temporarily restored. But the chaos in American-industrial relations will continue until some of the fundamental questions are faced rather than skirted.

The dispute between the government and Mr. Lewis posed several important legal questions, and had interesting political implications. On the legal side, there is the question as to the right of the government to secure an injunction against the strike in the face of the Norris–La Guardia Act, which forbade Federal Courts to issue injunctions in labor disputes, and made no explicit exception of the government in this connection. It should be remembered that Mr. Truman did not believe last May that he had the authority to follow the procedure recently employed against Mr. Lewis; in his speech to Congress during the railroad crisis he requested new legislation to authorize precisely such steps. Congress refused to grant his request, but the President has followed the procedure anyhow. There are good grounds for suspecting that the government has a weak legal case, despite the report that the Supreme Court will probably uphold the ruling of the Lower Court in favor of the government.

From one standpoint, this is a purely legal question, and the courts must decide whether the affirmative view of the Attorney General, or the negative opinion of the lawyers for the union is correct. But problems greater than those of the recent crisis are involved—namely, whether government is superior as sovereign to the laws it has made, and whether government as an employer should have power deemed inappropriate for private employers, and to what degree if any. Government has a greater responsibility to the total society than private employers have, and presumably should have power commensurate with its responsibility. How can such powers be granted without investing government with the role of strike breaker in every important dispute, and without making it in effect a sponsor of involuntary servitude?

Further, if government has the right to secure an injunction against a threatened strike, by what methods can the injunction be made valid practically as well as legally? In Pittsburgh a few weeks ago the leader of a power workers’ strike was thrown into jail for contempt of court, because he ignored an injunction obtained by the mayor, only to be released a few days later, because he alone could modify the actual situation in Pittsburgh, and his imprisonment had only served to strengthen the strike. The prestige of the courts is not enhanced by steps which may be legal, but are impossible to enforce.

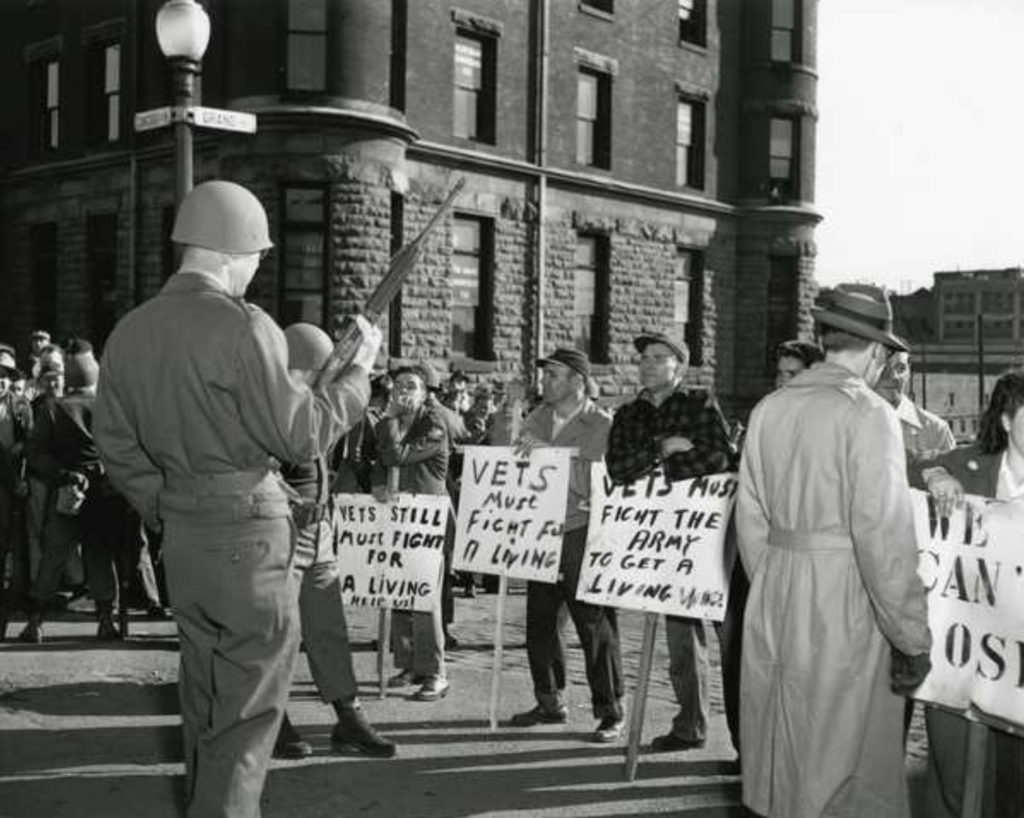

No formula for compulsory prohibition of a strike by a major union is immediately available, and it is doubtful that one can be devised within a democratic framework of opinion and of government. The imprisonment of a union leader, or the imposition of a heavy fine against him, or the union, will not often stop a strike; the total effect will ordinarily be to the contrary. The use of troops in the coal fields will be equally futile—the very suggestion that they be used, to protect miners who might wish to work, betrayed a remarkable naiveté concerning the solidarity of the miners’ union.

On the political side, the fight between Mr. Lewis and the Truman administration has its tragicomic aspects. With a sharp eye toward the 1948 elections, Republican leadership is undoubtedly enjoying Mr. Truman’s latest loss of labor support, especially in view of the fact that the new Republican Congress is not yet involved in responsibility. The fact that Mr. Lewis has been the chief Republican stalwart in labor circles for many years (except in 1936, when he joined most of his fellow Republicans in deserting the party) should not be forgotten.

There are other issues that are of far deeper import than the immediate legal and political questions, though they have been hinted at in discussion of these questions. One such issue concerns the right of any group to imperil the economy of the nation—and, to a significant degree, to retard the recovery of economies elsewhere, if not actually to starve innumerable people. The obvious answer is that no group—whether meat growers or coal miners—can be sustained in any such right. Democracy does not grant the right to pursue group interest without regard for wider consequences, or to pursue group interest without restraint, even if this interest is coincidental in some respects with the total welfare. An unlimited right of this sort can be entertained only within the framework of anarchy, or of a totalitarianism which sets one particular group free to exploit all others without restraint.

A second fundamental issue concerns the right of a democratic government to coerce a great mass of its citizens, and to compel them to work against their will under conditions of which they do not approve. To be sure, the miners are not relatively disadvantaged at the moment in pay rates, or total income, or hours of labor, as compared with other workers. They are comparatively in worse situation with respect to living and working conditions, particularly housing and industrial accidents. But whatever the validity of their grounds, the simple fact remains that the miners have elected, unanimously, to accept Mr. Lewis’ cue for a strike. During fifty-six years of struggle in a rough-and- tumble industry, the United Mine Workers has taught its members in performance, as well as in theory, that their only reliable defense lies in union solidarity. The very character of the industry has helped to make the union a kind of super-government for its members, so far as their relations with the industry itself are concerned.

It is doubtful that the right of a democratic government to compel citizens to work against their will can be justified, except under dangers so imminent and catastrophic that the very existence of the democracy is immediately threatened, and no solution except compulsory labor is available. An analogy between military conscription and compulsion of industrial workers would be weak at many points; the danger of complete disaster is not so imminent as in wartime, nor is compulsion an effective method of meeting strikes.

A solution to the perennial difficulties between Mr. Lewis and the government must go deeper than a temporary compromise, or the determination of nice legal points. A long-range and basic program would require that the responsibility of the government, for the production of coal, should be matched by ownership by the government of the facilities for producing coal, in order that the conditions which breed discontent and give Mr. Lewis his power could be dealt with at the sources. In effect, the government has been operating the coal mines since last May without adequate authority to discharge its responsibility effectively. Basic ownership of the mines has remained in private hands, to which the government has been required to make an accounting. The government assumed authority to meet ephemeral demands of the miners’ union without assuming authority to reorganize the coal industry in such fashion that subsequent demands—and Mr. Lewis’ pugnacity in prosecution of them—might be mitigated. The government has really been a personnel manager rather than the owner of the business, and its role has been superficial. It has at last degenerated into an attempt simply to maintain the status quo in the industry.

It is fatuous to expect that a Republican Congress which is already pledged to “take government out of business” will approve nationalization of the coal industry. The new congress is far more likely to search for a repressive formula for control of union leadership and compulsion of workers. Some types of labor legislation, such as authority for government agencies to investigate and publish all relevant facts in a dispute (including a “look at the company’s books”), are long overdue. The establishment of a system of labor courts, the strengthening of the government’s mediation service, the regularization of national and regional labor-management conferences—all such devices for promoting consultation and facilitating adjudication would help to lessen industrial strife. Management and the unions might also be encouraged to experiment with systems of grievance machinery, group incentive plans, and annual wage schemes which have already proved their worth. Contracts in industries might be written on a regional basis with different dates of expiration, to the advantage of the union as well as to total economy.

But a higher order of industrial statesmanship than has yet been displayed by either the Democrats or the Republicans must emerge before such fundamental procedures are adopted. Meanwhile, despite temporary settlements and abortive legislation, we can expect crisis after crisis in American industrial relations, to the distress of real lovers of freedom and the comfort of extreme radicals and reactionaries.

Liston Corlando Pope (1909 – 1974) was an American clergyman, author, theological educator, and dean of Yale University Divinity School from 1949 to 1962.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!