Political operative, lawyer, statesman and diplomat James Baker was superlatively competent, pragmatic, charming, icy, devout, and profane. He was an inveterate leaker to the media whom critics saw as self-serving, and friends saw as savvy. He was Gerald Ford’s campaign manager, Ronald Reagan’s White House Chief of Staff and Treasury Secretary, George H.W Bush’s campaign manager and Secretary of State, and George W. Bush’s envoy in the 2000 Florida presidential election imbroglio.

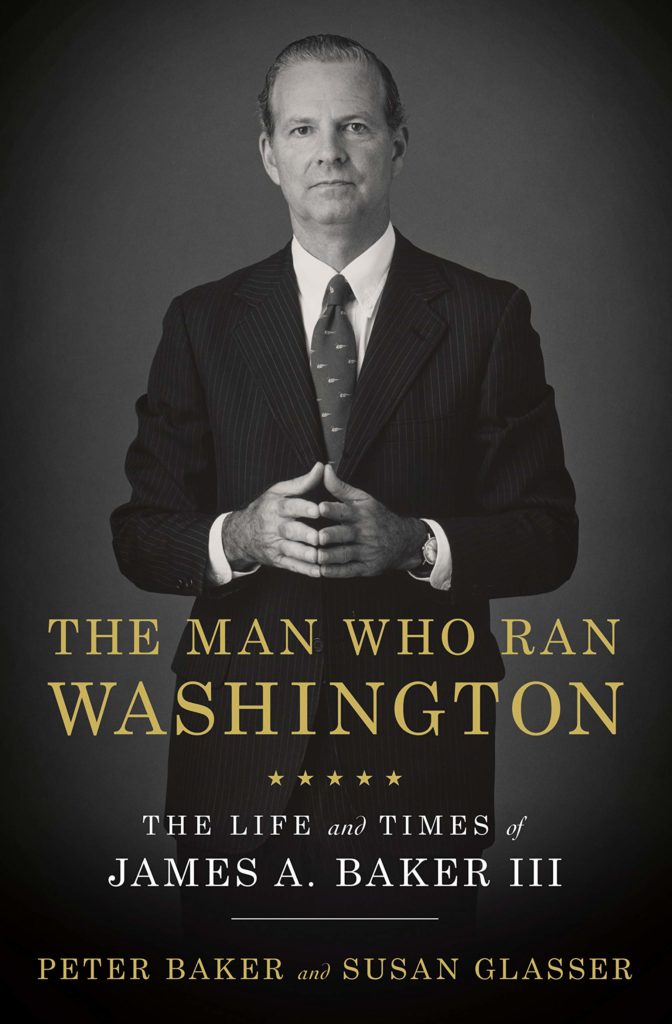

Reporters Peter Baker of The New York Times and Susan Glasser of The New Yorker, who are husband and wife, tell the story with their biography The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James Baker.

Baker was one of most important political figures of the last quarter of the 20th century. As chief of staff, he stewarded Reagan’s agenda during the first term, which included tax cuts, rearmament, and deregulation. He sometimes was half smilingly called the prime minister or deputy president. As Reagan’s treasury secretary, he presided over four years of an economic boom, interrupted by a brief stock market collapse that he helped manage.

Although an effective and cutthroat politico, the image conscious Baker preferred cabinet offices to campaign roles, which he was unable to escape. His entry into electoral politics began in 1970 when his country club tennis partner George H.W. Bush asked him to manage his unsuccessful campaign for U.S. Senator from Texas. Baker served only briefly in the Gerald Ford Administration, at Bush’s recommendation, but quickly gained such confidence that he became Ford’s 1976 campaign manager against Jimmy Carter, which almost succeeded. In 1980 he managed George H.W. Bush’s 1980 campaign for the GOP nomination in 1980, which successfully placed Bush as the primary alternative to Reagan. Baker helped persuade the relentless Bush to step aside when Reagan’s win became inevitable. Almost seamlessly, Bush joined the Reagan campaign to negotiate the debates with Jimmy Carter, achieving a schedule benefitting Reagan and assuring his election.

Bush utilized Reagan in 1988 to persuade an unwilling Baker to leave the Treasury Department to again become Bush’s campaign manager, when Bush began far behind Michael Dukakis. Baker withheld no punches in a campaign famous for the Willy Horton ad tying the Massachusetts governor to a paroled rapist murderer. In 1992, Bush again implored his friend to step away from the State Department, which he loved, to manage another underdog campaign, which this time failed against Bill Clinton. Bush’s defeat was the worst, as a vote percentage, for any sitting president since William Taft. Some Bush family and friends, mostly unfairly, faulted Baker’s lack of enthusiasm.

Baker’s final campaign role was in 2000, when the Bush family asked him to manage their team in contested Florida, which Bush officially won by only hundreds of votes, prompting calls for endless recounts. A hard-nosed Baker took no prisoners, in contrast to Al Gore’s initial envoy, a more decorous former Secretary of State Warren Christopher. Baker accurately assumed from the start that the U.S. Supreme Court would settle the outcome.

This skill for hardnosed negotiation came to Baker naturally, as he was the son, grandson, and great grandson of prominent and successful Houston attorneys. Baker was born to wealth and privilege but had his share of sufferings, chiefly the death of his first wife by cancer, leaving him a widower with four young sons. He married his second wife, Susan, who already had three children, and with her had one additional child. A loving but frequently absent father, Baker’s sons suffered from addictions and other troubles. Baker delegated parenting to Susan across his service in three presidential administrations.

Wherever Baker landed he accumulated trust, responsibility, power, and resentment. Many conservatives abhorred his prominence in the Reagan Administration, believing he was a wily political moderate who subverted Reagan’s conservatism. But he retained the trust of both Reagans, especially Nancy, who esteemed competence over ideology. Baker was a conventional wealthy Texas conservative who was supremely pragmatic. He sought to escape the exacting role of White House chief of staff to become National Security Advisor, which conservative Reaganites blocked. Almost certainly in that role Baker would have averted the covert sale of arms to Iran that exploded into the Iran-Contra Scandal, which nearly wrecked Reagan’s second term.

Baker’s most important and most cherished role was as Bush’s secretary of state, where he managed the end of the Cold War, the reunification of Germany, the end of the Soviet Union and the Persian Gulf War. His close partnership with Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, which began with Baker’s hosting him at his Wyoming ranch, was key to his success. The Persian Gulf War victory was followed by the Madrid Mideast Peace Summit of 1991, which Baker helped achieve through months of excruciating Mideast diplomacy, including many unpleasant hours with Syria’s unsavory Hafez al-Assad.

His lack of ideological principles in favor of practicality and negotiation makes Baker’s formal speeches and comments not especially interesting, much less soaring. He was not a crusader or an idealist, but a steely realist focused on the possible. He did not cast visions but managed situations and implemented the vision of others, such as Reagan. Baker believed in America but did not try to articulate its music.

Raised Presbyterian, Baker became an Episcopalian during his second marriage to Susan, who was devout. The death of his first wife seems to have strengthened his faith although it did not inhibit his resort to profanity in humor or in anger. Baker and his wife belong to St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston, a large conservative congregation that George and Barbara Bush also attended. Only briefly cited in this biography, in 2012 the Episcopal Bishop of Houston collaborated with Baker on a compromise allowing churches in the diocese to decide on same-sex unions. Baker’s own views on same-sex marriage were subservient to a negotiated settlement, which he explained as “some issues can be so vigorously contested that resolution of them is unreachable” so “the most practical approach usually is to address those matters where progress is possible, postpone decisions on irresolvable issues and mutually respect the differing opinions of each side.”

This approach in politics and diplomacy made Baker often unappealing to advocates of conviction politics but indispensable to situations needing practical results. Probably Baker is unfamiliar with the school of thought known as Christian Realism. But in his lack of illusions about the world, and in his pursuit of the national interest, he qualifies as an adherent.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!