Starting on September 27, the war between Azerbaijan and the Republic of Artsakh resumed. Also known as Nagorno-Karabakh, Artsakh is a region within Azerbaijan that is predominately Armenian, and since 1994 has been controlled by Armenians. The war ended on November 10 with the Armenians of Artsakh losing most of the territory it had controlled. In this episode, Robert Nicholson of the Philos Project talks with Mark Melton about why this war happened, how Turkey was involved, what the Armenians are losing, what the US government should do next, why the world didn’t help Artsakh, and what may happen to Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan now. Melton and Nicholson also cover how this conflict fits into region’s geopolitics and how this all affects the United States. Finally, they discuss what Recep Tayyip Erdoğan may do next, particularly in Cyprus, and what the Biden administration should do more broadly in the Middle East, especially with the Arab–Israeli peace movement.

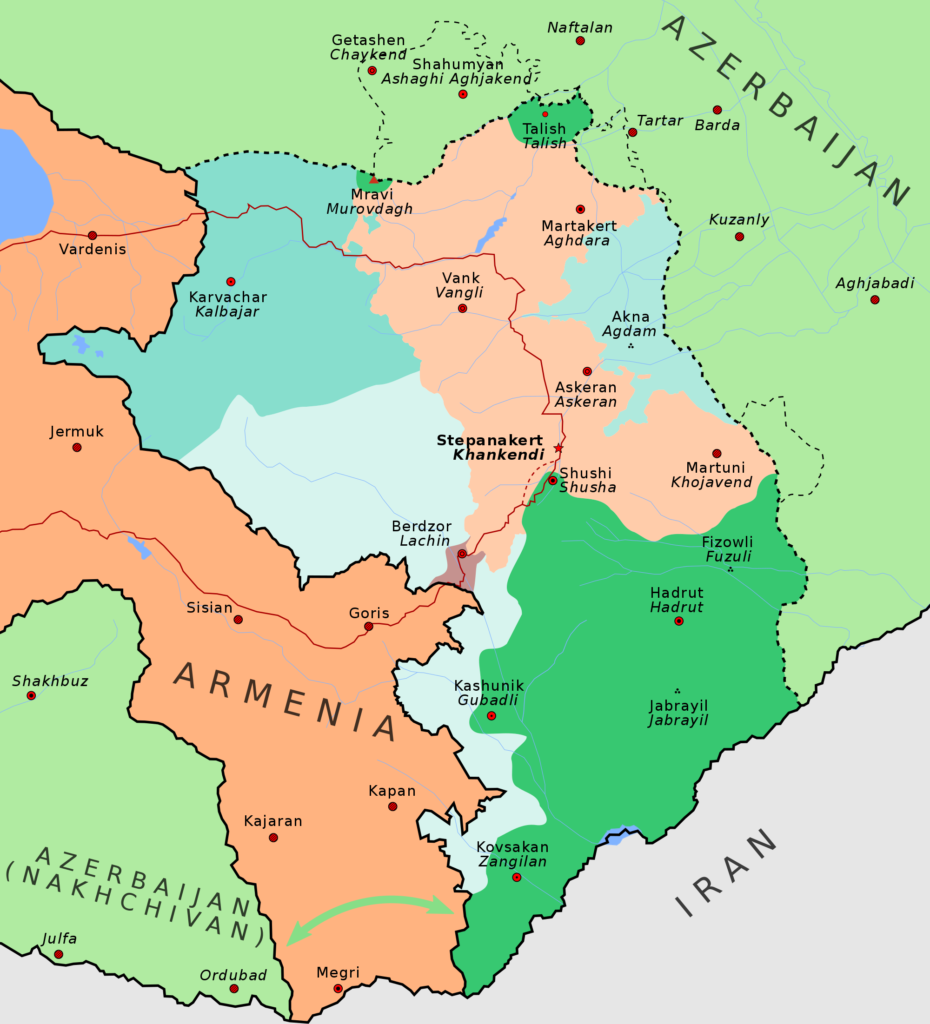

Maps of the Region:

Rough Transcript

Mark Melton

Welcome back to the Foreign Policy ProvCast. My name is Mark Melton. I’m the managing editor for Providence and today I am speaking with Robert Nicholson who is the president of the Philos Project based in New York. And first off, Robert, thank you so much for joining us today.

Robert Nicholson

Well, thank you, Mark. Good to be here.

Mark Melton

So starting on September 27, the war between Azerbaijan and the Republic of Artsakh resumed. This area is known as Nagorno-Karabakh and Artsakh is a region within Azerbaijan that is predominantly Armenian and since 1994, has been controlled by the Armenians who are predominantly Christian. Before then the Soviet Union controlled this area. The war ended recently on November 10, with the Armenians and Artsakh losing most of its territory. And this weekend, we saw videos of Armenians torching their homes before their region were transferred to Azeri control and most territory will be transferred in the next couple of weeks.

So Robert, why did this war happen?

Robert Nicholson

Well, that’s a great question Mark, and it depends on who you ask, as far as what answer you’ll get. The details are still quite fuzzy, actually. And I’ve heard differing reports from people who are invested or one or the other side. What we do know is that the latest round of fighting started in September, after some clashes or skirmishes -they’re described in different ways- that happened over the summer. And although I am under the impression that the Azerbaijan military was the first to initiate the attacks, it’s not entirely clear and I can’t prove it. What I do know is that the fighting began in earnest when the Azeris began, invaded, and started taking ground in this Republic of Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh, as it’s sometimes called. And the war proceeded from there until just last week.

But it’s also important to note -and I don’t know how much we’ll get into this- but, you know, looking at this conflict as one that began in September or even this year, is really to understand the situation, as seen through a straw.

This is a much larger conflict that’s been going on for years, at the very least since the 90s and arguably, long before that, as the Armenians have tried to maintain a foothold in their homeland, their ancient homeland. They’ve been living in eastern Anatolia for you know, since before Jesus was born. And slowly, slowly over time, they have been subject to these sorts of invasions, these acts of aggression. And little by little they’ve lost land as they have in this latest conflict.

Mark Melton

Yeah, it’s been a pretty long conflict. And while I was researching into who controlled the territory in the region and when it gets pretty complicated. And of course, for those listeners who don’t already know, Armenia is known as being the first Christian nation, because the state established Christianity as the state religion in AD 301. But, Robert, what has Turkey’s role been in this conflict?

Robert Nicholson

Well, one thing that’s important to know and I’m sure you know, but I’ll say it anyway in case there are people out there who don’t, is that Turkey and Azerbaijan, both of which are located on either side of the Republic of Armenia and this republic of Artsakh, are Turkic states. Ethnically they are the same. They identify as Turks, their languages -although somewhat different- are Turkish languages. And although they are different in terms of their religious practices, one being Sunni Muslim Turkey and the other being Shia Muslim Azerbaijan, they very much see themselves as brothers states. They sometimes call themselves ‘two states, one nation.’ And throughout the years, throughout the decades, Turkey has been very supportive of Azerbaijan, both during Soviet times and all the way up until very recently. And they see themselves as part of the same unit and of course, Turkish President Erdogan has dreams as many have written about, of a pan-Turkic union, or an Islamic caliphate.

And whichever way you take that, what it means is that he sees the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan as very much tied in with the well-being of Turkey itself. So they work very closely together. In this recent conflict, Erdogan did pretty much everything one could do to support a state at a time of conflict. He certainly was on the airwaves, making all kinds of pledges of loyalty and support, you know, bombastic threats against Armenians. And then backed up all of that rhetoric with arms and very explicitly, very publicly, there was really no shame about it. They had worked Turkey and Azerbaijan over the summer in joint military exercises. And it was pretty clear that Azerbaijan perpetuated the conflict as long as it did -over a month, about a month and a half- because it had such strong support from one of the biggest and most powerful states in the region.

So Turkey’s role was was huge. And if you take Turkey out of the equation, this conflict would have been very different at the very least, much, much shorter.

Mark Melton

And what are the Armenians losing? For instance, I know they’ve lost some monasteries, and they’re losing a lot of territory, as I mentioned at the top of the show. So what is it that Armenia is losing here?

Robert Nicholson

Well, there’s what they’re losing concretely, and then there’s what they’re losing more intangibly. Concretely, they’re losing -maybe most importantly- the city of Shushi or Shusha, as it’s sometimes called. This is a very ancient city that is located in this region of Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh, and it is known to be something of a holy city. There are many churches and ancient Armenian properties and heritage in this area. And the loss of Shushi is maybe the most difficult pill for the Armenians to swallow.

There’s also a number of other territories in this Republic of Artsakh that are being lost. There’s been videos on social media of Armenians burning their houses down, as they’re forced to withdraw, as these territories will be given over to Azerbaijan. We see videos of people gathering in front of very old Armenian Orthodox churches singing, holding hands, knowing that this could be the last time that they see these kinds of things.

So they’re losing quite a bit of physical property, if you want to call it that. But there’s also the the intangible loss of yet more indigenous Armenian land. As I said just a few minutes ago, Artsakh was a thing for Armenians, was a territory they controlled, almost 200 years before Jesus was born. This is very, very old. The Armenians have been there for a very long time. And of course, the Turks, whether they’re Azeris or Turks from the Republic of Turkey, didn’t arrive in the area until at the very least the sixth century AD and mostly not until the 9th, 10th and 11th. So these Armenians have been gradually shrunken down into smaller and smaller… a smaller and smaller piece of land. And this, you know, on a map for people living in a massive country like the United States, these lost territories may seem small and maybe even irrelevant, but for Armenians, it’s just another scrape at the apple. And they can’t help but think about how long it’ll be until until everything’s taken from them.

So, you know, I hear some people talk about this as just being a border dispute, trying to downplay the significance of it. But for Armenians, especially in light of the Turkish genocide that happened only a century ago, this was an existential conflict and the loss of these things, is really a major, major blow to the nation.

Mark Melton

And Philos project published an open letter to the Trump administration and Congress, calling on them to help the Armenians. What would you want the US government to do now?

Robert Nicholson

Well, in that letter, which was interestingly submitted contemporaneously with the ceasefire -and I’m talking about mere minutes. I wish I could say that the letter was responsible for that. But in the letter, we asked the US administration in Congress to condemn Turkey and Azerbaijan for their aggression against Armenia and Artsakh, especially against the civilians and churches. And we said that that condemnation should include arms embargoes, targeted sanctions, whatever tools are available to hold these states accountable.

We also called for the US government to suspend military sales to both countries until the aggression ceases and until Azerbaijan withdraws from the territories that they took.

Thirdly, we asked the US to send direct or indirect if needed, humanitarian assistance to Armenians in the zone of conflict.

And then lastly, we called for the US government to initiate diplomatic efforts to resolve the status of Artsakh, which is disputed -we haven’t talked about that- but to initiate efforts that would finally resolve the limbo that Artsakh and its people find itself in, in a way that safeguards the rights of the Armenians living there. Just a small parentheses here: for those who don’t know, this area, Republic of Artsakh, it is declared to be a country by the Armenians who live there. But in the eyes of the international community this is a part of Azerbaijan. It’s a breakaway region, a region that declared its autonomy and independence, and remains unrecognized by most of the countries of the world. From Azerbaijan’s perspective this is part of Azerbaijan. But for the Armenians who’ve been living there since long before the Azeri Turks ever showed up in the region, this has to be part of the the Armenian people’s self determination.

So that complicates this whole question. And I think it really made a US response difficult, which is why I think that this last point, this diplomatic efforts point, it may be the most important, certainly to avoid, you know, another conflict in the future and the conquest of even more of Artsakh’s land.

Mark Melton

And so Armenians seem, I would say from my perspective, they seem to have a good network of soft power, especially through its diaspora. And I saw Armenian activism not just from people I know through Providence and the Philos Project, but other sources. Even Conan O’Brien has an Armenian on his staff who’s pretty vocal, and I follow Conan O’Brien. And so it’s interesting seeing her on Instagram posting about this from a very different perspective than the Christian foreign policy community. And so why wasn’t the world able or willing to do more to help Armenia?

Robert Nicholson

Well, that’s really the big question. I think part of the problem is that the fighting took place in this disputed region. And it’s, you know, it’s very difficult to come down on the side of a government that you don’t recognize. I think another problem was the moment; I think Azerbaijan and Turkey were very aware that 2020 is a little crazy. And more importantly, that the American political moment is just completely insane. And that’s why I don’t think there was any mistake in the fact that these hostilities broke out when they did, just a short time before the US election when everybody knew that Americans were paying attention to nothing else. Lastly -and this is maybe the most important reason- is that America, although some people in the policy community are waking up, has typically been extremely pro-Turkey, and I mean to a fault. And that’s largely because Turkey has been a strong ally through the Cold War. It was geopolitically very important for our confrontation with the Soviet Union. And even until today, remains an important way for us as the US to balance the power of Russia. And what that’s really meant is that we’ve more often than not given the Turks a free pass. I mean, you can just look in the last year or two years all that President Erdogan has been doing with not even a slap on the wrist from the United States.

He’s in Syria, largely with the agreement of the US. He’s in Libya, he’s threatening Greeks, and Cypriots in the eastern Mediterranean. He’s obviously active in Artsakh. He’s supporting Hamas. He’s, you know, when the French teacher just a few weeks ago, showed that cartoon to his class, he was one of the people saying how awful that was, and I think played some kind of ancillary role in fanning the flames of Muslim hatred that resulted in some of the deaths that we’ve seen. So he is a rogue actor and he is very aware that the US needs him. And he is pushing the envelope just about as far as he can.

So I think that when these, you know when this moment happened, there were people in the State Department who -and in the White House- who were thinking ‘this is not good, we should do something.’ But because there is this bias toward Turkey, this fear of rocking the boat, this fear of driving Erdogan even further from the west, I think a lot of people turned a blind eye. And that’s not just me speaking anecdotally, this is something I’ve heard explicitly from people in house. The good news is that policymakers more than before seem to be getting a handle on just how bad Turkey is, and realizing that if we don’t draw a line in the sand soon, we’re going to have to do it anyway when the situation is even less in our favor. But for the time being, this I think remains one of the major reasons why the US and even the West more broadly, kind of look the other way, while Artsakh was was conquered by the Azeris.

Mark Melton

So obviously, the Republic of Artsakh, if I’m pronouncing that correctly, has lost a lot of territory. But this also has a lot of ramifications for the Republic of Armenia. So what do you think happens to the Armenian Prime Minister, if I pronounce his name correctly, Nikol Pashinyan?

Robert Nicholson

Pashinyan, mhm.

Mark Melton

Pashinyan. So what do you think will happen to him? Actually, did you post a picture like do you know him? Or have you met him?

Robert Nicholson

The President. I posted a picture of Armen Sargsyan. I have not met Pashinyan. But Pashinyan’s in a lot of trouble right now, if you’ve seen any of the videos that came out of Yerevan just a few days ago. I mean, the Armenian people are absolutely traumatized, outraged. You know, there’s some fear that Pashinyan himself, maybe in real, personal danger. I mean, you can imagine just sort of putting yourself in the head of these Armenians, people who see themselves as a beleaguered people, surrounded on all sides, landlocked, losing ground steadily, steadily for centuries. Now to see their own leaders, someone that was in some sense the Golden Boy, someone who came on the scene just a few years ago to bring Armenia to a new place, into the 21st century. To see this man giving up huge chunks of land to the Azeris, it’s treason in the eyes of many people. And Pashinyan is really on the ropes, trying to explain why he did it, to explain that it was either stop there and cut losses or lose everything. But many Armenians are not buying it. So it’s unclear to me, whether he’ll stay. Many are demanding his resignation, if not worse. I think there’ll probably be some kind of shake-up. It’s hard to see how he’ll be able to maintain his legitimacy after something like this. But even his resignation won’t solve the domestic crisis that the Republic of Armenia now finds itself in.

It’s a moment of soul searching, of questioning, of second guessing. It’s a moment of doubting an assumption that has been growing for a few years in Armenia, which is that Armenia should try its best to get closer to the US and closer to the West. And of course, the West’s just complete silence on this issue, I think makes many Armenians feel that really, they have no friends apart from maybe Russia, and to some extent, Iran. But even there, I think Armenians know that neither of those countries really have their best interests at heart anyway. So it’s a really tough time for Armenians right now in the Republic of Armenia. And of course, that’s not even talking about the people who lost family members in the fighting.

Mark Melton

Right. And speaking about Russia, so obviously, Russia is a major player in the area, they used to control the area during the Soviet Union days. And Russia was a broker of the final Peace Deal and that they’re going to send peacekeepers into the area. And I’m not sure if Turkey’s sending in peacekeepers. I’ve saw some conflicting reports on that. I’m not sure this morning, of the state of that. So geopolitically and regionally, I would say it seems that Russia is a major loser in this conflict and that Turkey is a major winner. This is because Azerbaijan and Turkey were unsatisfied with the status quo of Armenians controlling Artsakh and they used their military power to change the facts on the ground to suit their agenda. Meanwhile, Russia, I believe, was satisfied with the status quo. They have pipelines going nearby and so having conflict near these pipelines was probably not what they wanted. But Turkey was able to push their weight around. And the Russians went from being an uncontested power broker to having to deal more with Turkey.

In this I see kind of a continuing trend of Russia losing power in its near abroad, whether to China and former Soviet states and Central Asia, or European Union friendly populations in Ukraine and other Eastern European countries. But different analysts have different takes on this particular viewpoint of who is the winner and loser, broadly, beyond the Armenians and so forth. So other than the Armenians, who do you think are the major winners and losers? And, in particular, what does this mean for Iran?

Robert Nicholson

Well, that’s a great question. And one of the big arguments on the other side of this throughout the course of the latest conflict was that the US should not help Armenia, because Armenia is quote-unquote ‘in bed with Russia and Iran and helping them only strengthens our enemies, whereas Turkey and Azerbaijan are,’ you know, in this telling ‘our allies.’

I think you’re right that Turkey is the big winner here. I mean, Erdogan went for it and no one did anything for over a month. And his people, his allies, the Azeris, gained ground, the Armenians lost ground and he emerges, I think more powerful than he was at the outset. Now, President Elect I’m not sure what his technical status is right now, Joe Biden, I won’t get into that mess… but he actually, interestingly, was fairly vocal during the conflict on the side of the Armenians and Turkey is aware of that. Turkey, of course, is trying to figure out like everyone else, what comes next? What is American foreign policy look in the caucuses in the Near East, under a Biden administration? It seems like it may be more anti Turkey than the Trump’s administration’s policy was. It’s unclear. But I think one of the reasons why the fighting stopped when it did was that everybody was sort of taking a breath to figure out what comes next from the US direction.

One thing I know for certain is that the US doesn’t gain much here, apart from maybe as you say, the energy lanes being intact at the end of it. And Azerbaijan as a major energy supplier, you know, remaining solid.

I do think there are some benefits for Russia. I agree that it’s not a clear win for Vladimir Putin. But you can imagine that Putin’s ability to broker the conflict to a ceasefire is in and of itself, evidence of some residual power that he maintains in his near abroad. Now, it’s certainly not as strong as it was into the Soviets, or maybe even as strong as it was 10 or 20 years ago. But I do think that it’s worth noting that Putin was the only one who was able to make it stop the US either could not or would not. And it was he who stepped in and brought the parties together. So the fact that Russia will have peacekeepers on the ground, I think, you know, it gives Putin a reason to, you know, demonstrate his power in a place beyond his borders. I agree with you that it’s unclear where turkey or Turkish soldiers will fit in that regime, but they will be present either in these territories of Artsakh itself or stationed just over the border in Azerbaijan. So it’s interesting to see and even the fact that Putin and Erdogan have been in touch more recently, although kind of historic enemies, Turkey and Russia. It could be that under a Biden administration, the two actually find more common cause than they have in a long time. Now, as far as Iran. Iran is an ally of Armenia, the border with Iran is one of the few that Armenia sees as stable and safe, they have trade relationships, all kinds of things like that. But it’s not exactly clear, especially under a pretty brutal sanctions regime that Iran really is better off one way or the other. They were mostly quiet during this time. And I think that’s just a testament to the pressure they’re under from the US under the Trump administration.

Mark Melton

And I’m going to be posting some maps online with the podcast page so that we can kind of see for the readers who aren’t our listeners who aren’t that familiar with all the geographic areas of how these countries are connected. And I actually didn’t realize how Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkey, how their borders are so close together in that little tight corner. But anyways, and also, in the map show like the territory that the Artsakh lost.

And so to kind of move, you know, to Turkey and what’s going to happen next, we see some talk now about Erdogan wanting to call for a two-state solution in Cyprus. And so do you think they are going to focus in on that and what do you think the Biden administration would do or should do?

Robert Nicholson

Well, I think the timing is interesting, just to sort of point to what I said before that Turkey, that Erdogan feels like he needs to make some kind of concession -I don’t know that that’s the right word- but, you know, demonstrate his peace bona fide. I think that the situation in Cyprus is and has been since 1974, untenable. The fact that Turkey, a NATO ally is occupying an EU Member State is truly insane. The fact that no one talks about that or very few people. The fact that Turks have built settlements to use the analog from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is pretty notable. But the fact that very few people really talk about it or get all that upset about it is to me even more notable. Just goes to show you how people pick and choose the issues that are important to them.

I do think a situation or resolution in Cyprus is needed. I think Biden should pursue it. But I don’t think that Biden should cave and I would say across the board, the US -whatever happens in Cyprus- needs to re-evaluate and really strengthen its position vis a vis Turkey, and there are lots of different ways to do that, short of any kind of military engagement, lots of tools in the toolbox. But this, you know, extremely pro-Turkish policy that we’ve had in place for decades has really run its course. To say it’s living on borrowed time is an understatement, right? This Turkey that we’re looking at today is not the turkey of 1950, 1990. Or even, you know, 2000, I mean, for the last 10 years, the situation has been getting worse and worse. And I think that the Biden administration needs to, as I said, draw a line in the sand. And there’s rhetorical ways that that can be done: recognizing the Armenian Genocide at the executive level. There are economic ways, there are, you know, just tougher approaches to negotiation in Cyprus and other places that could actually contain this Turkey problem in a way that it hasn’t been done really over the last four years.

So I would say that for Biden, Turkey should be very close to the top of his list of priorities. The sooner we do something, the better. I think, personally, that we’re going to be dealing with Erdogan for the next 10 years unless something changes. And it’s important that the US position itself to not cut Turkey off. That’s not what I’m talking about. But to have a much narrower policy toward Turkey, that allows us to work with its people, its army, its intelligence services, while also standing up for these kinds of aggressions, especially, especially when they’re committed against regional minorities like Christians. You know, for all of the the anger that’s been directed against the Arab world for the last 20 years ever since 9/11 and it’s mistreatment of Christians and other minorities, and certainly there has been a lot of that, it pales in comparison historically to what the Turks have done to Christians. No, no group, no state has persecuted discriminated against, or murdered more Christians even close to what Turkey has done, certainly in the last 100 years, but even in the last few centuries. So I think that the Biden administration for that reason, a moral reason, but also lots of geopolitical reasons, needs to do something. And I think that a reevaluation of the Turkey policy is the first place to start.

Mark Melton

And you know, this week… Oh, by the way, we are recording this on November 16 in case listeners are wondering and if facts on the ground change at all. But this week you wrote a, or are writing an op-ed about what other recommendations you would give to the Biden administration. So to kind of close this out, like more broadly in the Middle East, like what is your recommendation?

Robert Nicholson

Well, I think there’s one big one. And I think it has to do with continuing the Trump administration’s policy of encouraging, supporting, strengthening the emerging alliance between Israel and Arab states throughout the region. We saw just in the last few months, this slew of somewhat surprising peace deals between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan. And all reports I’ve read point to the fact that there could be as many as half a dozen others in the waiting.

And I think that although Biden was elected, in many ways to roll back everything that Trump did, both domestically and in the foreign policy arena, I think it would very much behoove him to carry that particular policy forward. This is just not something we see every day, right? These states, these Arab states, especially Sudan, which was really out of left field for a lot of people, a big giant Arab state that has sponsored terrorism for decades. This is a really, really big deal. And for those of us who really work hard for peace in the Near East, this is a windfall, and we would be crazy not to keep that going. Partisanship should not get in the way of that. And I think that Biden administration actually could go even further than Trump, not just, you know, welcoming those Arab states that have still yet to make a peace deal with Israel, but also possibly, maybe, even bringing the Palestinians back to the table, you know, welcoming them to this peace party too. Of course, the Palestinian leaders boycotted Trump and Jared Kushner and the Trump peace plan that was offered just last year. But you know, a new president brings new opportunities. And I think that Biden could use that fresh mandate as leverage to work toward something that seems right now almost impossible, but with the right approach could actually come to be and I’m talking about a post normalization Palestine, right? It’s not something that I would put at the very top of the agenda. The Palestinians have been offered a number of deals over the years and have said, ‘no,’ so I don’t know that Biden should exert himself too much. But I think there is a desire on the part of Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority, the Palestine Liberation Organization, to come in out of the cold. You can imagine that for the last couple of years, they’ve, although very much opposed to Trump and Kushner and everything that they did, want some progress, right? They want to be welcomed back into the community of nations, and in particular, the community of Arab nations. They feel for good reason, pretty ostracized right now, as these Arab states are making deals with Israel. And I think that under the right conditions, and maybe specifically under the right leadership, something like that could be possible. So Biden actually comes in with a lot of leverage, both for continuing this rash of peace deals, but also trying to woo the Palestinians to do the same. We’ll see if it’s actually possible, but I think it’s absolutely worth a shot.

Mark Melton

Well Robert, thank you so much for joining us today, remotely, on the Foreign Policy Provcast and giving all of your insights and analysis on, you know, this conflict and everything that’s going to happen.

Robert Nicholson

Well, thank you, Mark. I always enjoy being on and keep up the good work.

Mark Melton

Thank you.