The following lecture was recorded during Providence’s 2017 Christianity and National Security Conference.

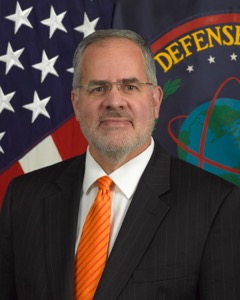

David Shedd underscores the relationship between intelligence and national security. He argues that intelligence is the first line of defense for the US as it provides it with information to make appropriate military and political decisions. He argues that espionage is a moral good because it defends state interests and protect citizens.