Editors Mark Tooley and Marc LiVecche discuss their respective pieces on Afghanistan here and here, Fuller Seminary’s Matthew Kaemingk’s new book Reformed Public Theology and Marc’s “debate” with Providence contributor Joe Capizzi of Catholic University on the 1945 U.S. atomic strikes on Japan.

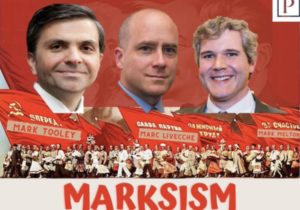

Tooley: Hello this is Mark Tooley, editor of Providence: A Journal of Christianity & American Foreign Policy, with another episode of Marksism, with fellow editor and fellow Mark(c), Marc LiVecche. We’ll be discussing several pieces from Providence this week, starting with the topic of Afghanistan. I wrote a piece, Marc LiVecche wrote a piece, we posted pieces also by our other Mark, absent today, Mark Melton, as well as contributing editor Eric Patterson. My own thoughts were along these lines, obviously what’s unfolding in Afghanistan is a great tragedy. It parallels to some extent what happened in Indochina 45 years ago in that America fought and contended for 20 years on behalf of a regime that was somewhat corrupt and unfit, but infinitely preferable to what sought to replace it, and lost many lives in the process, and hundreds of billions of dollars. But after two decades, the American people simply lost interest and pulled back, and that regime fell to a far more tyrannical force. That seems to be the case in Afghanistan, as Marc LiVecche notes in his piece. American forces in Afghanistan, no less than Indochina, fought valiantly and never lost battles, but ultimately, it was a political defeat in that the regime could not cohere the nation and the American people simply lost patience. But your thoughts, Marc LiVecche?

LiVecche: Yeah, exactly. That’s a good summary of what I had to say. Waking up this morning and reading the news, an analogy to Indochina seems like good news. It seems more like what was in 1979 in the fall of Iran and hostages and all the rest. So, you kind of scramble to find some semblance of a silver lining in all this, and none of them are good. A lot has been said. My emphasis, I think as you noted, somewhat falls on my love for America’s war fighters. And, once again, I think the sense of betrayal that they must be feeling and the question as to whether or not the sacrifices they made have been worth it, will be worth it. As you say, they didn’t lose the fight. They did their job magnificently. And especially with the work that I do on moral injury, one aspect of moral injury is the feeling of having been betrayed by someone in a position of authority over you in a high stakes situation. This is precisely that. It is a high stakes situation in which people lost friends lives, loved ones lives, and much else, because they believed that the fight was worth it. And America, I note in my piece, has an implied moral contract with our war fighters, and we will not send them into harm’s way unless the fight is worth it. We will take care of them in body and soul as we do so. And I think our end of that contract has been broken, and that is our national shame. You and I talked last night that throughout my piece, I’m writing and I’m talking about how our national leaders betrayed our fighters, and I kept having to self-correct that. Because, as you said last night, our national leaders, cowards as they may be, have, nevertheless, given the American people precisely what they appear to be asking for. Not to a person, many of us have been asking for something else, but it would be unfair to pin this exclusively on our leaders. I think we as a nation have let our war fighters, and maybe just as importantly, our allies in Afghanistan as well, we’ve let them down. And that’s a shame.

Tooley: And it’s true for democracies that wars can only be waged with public support, and public opinion is the fickle, but not entirely illogical in losing patience after many years or two decades. So, tragic, but not surprising in that sense. There’s also, I think that the American people are not fickle, but I think to their better or to their worst nature, Americans want to reshape the world in their own image. And they want to do good where they can. And it will not be surprising if in the next 10 years, America intervenes in another nation and attempts to rebuild it with the best of intention. So, the cycle continues.

LiVecche: Right. It won’t be terribly surprising if we invade a place called Afghanistan. I do wonder, you’re absolutely right. There’s no question that those are American tendencies. I’m no expert on the history of Afghanistan, but I read novels and some papers about Afghan history and wonder to what degree it’s entirely true to say we’re trying to foist upon, I don’t hear you saying this, but some commentators have, that we’re trying to foist upon Afghanistan a completely alien view of what the good life is. I read about Afghanistan in the 1970s, and at least in Kabul, there was apparently a reasonable degree of liberalism or liberal-likeism, where it wasn’t Western values, but there were sort of basic human values. Women were relatively emancipated, or entirely emancipated in some ways. So, all that to say, I think there were things, human tendencies, that we could have built on without making them a democracy. Democracy is not working so well here; let’s not export it everywhere else, but just basic kinds of human decency that Afghans are just as capable of enjoying as anybody else. I don’t think it’s fair to say, “it’s just an Islam problem. They’ll never reform.” We’re different, we have different histories, it is a longer conversation, but in some ways, the Islamic tradition is Hebraic-like, right. I mean, we share an awful lot of the history, and so I don’t accept that there was never anything that we could have built upon. That the only choice was to make them like us or to leave them, like sort of a tribal Wild West. But I’m no expert on it.

Tooley: If there’s any small kernel of potential good news, unlike in Indochina where Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos were quickly Sovietized by totalitarian regimes, it seems unlikely the Taliban has the organization or the ability to enforce its will on the entire country. And inevitably there will be resistance to it that will be messy and horrible in many ways, but I don’t think 10 years from now Afghanistan is going to be Calvinized. What do you think?

LiVecche: Probably not.

Tooley: Well, moving on, I did an interview this week with the editor of a new book on reformed political theology, authored by an ethicist teaching at Fuller Seminary, Matthew Kaemingk. And I found it very insightful and helpful in that it, in keeping with the themes of Providence, is their response to the vacuum in political theology within American Christianity today. It lifts up the Calvinist tradition. And as Matthew Kaemingk pointed out, Calvinism, along with Catholicism, does not demonize or minimize political power. It understands that political power can be used for good, it’s ordained of God, and Christians have a responsibility to accept it and to utilize it responsibly. So, your thoughts, Marc LiVecche? I think you’re very much in sync with this message.

LiVecche: Yeah, completely in sync. It’s why you successfully hired, or attracted, me to be editor of Providence. Absolutely. Power is a good. Matthew pointed that out. Like all goods, human beings have a wonderful ability to pervert it and use it for ill. But it is a created good. God has power. It’s not simply a good; it’s a good that Christians are supposed to wield. We were given dominion over the world. That’s providential care. You can’t care for anything if you don’t have the power to do so. So, power is not something that we should shy away from as Christians. It is in fact something that ought to be cultivated. And I think that plays all the way upstream, or it’s not just individual Christians who should cultivate power, but it’s also nations that cultivate power to the degree that they are capable of cultivating it, without excluding other goods unproportionally, indiscriminately, and all of that. Yeah, I don’t think it’s an accident that America has great power. I don’t think we just woke up one day powerful, and therefore capable of doing enormous acts of good across the globe. And getting those things wrong and all that as the caveat. But we’ve cultivated that power as a kind of moral duty, and now it’s up to us to wield that power for good. So, I love his emphasis on power. That’s absolutely right. Power chastened, as he also said, by recognition of the reality of sin. And therefore, how a theology of sin is absolutely essential for anybody, in private life and in public life as well. Maybe even more so in public life in some ways, because you’re not dealing with just one or a handful of sinners, you’re dealing with a nation of them, in relationship to other nations full of other sinners. And so, his emphasis on power and on sin, therefore, on the importance of mediating institutions between the nation and state, which kind of brings us back to the Afghanistan project. You’re not going to ever change anybody militarily or purely economically. You’ve got to build institutions that allow a thick space to begin to emerge between the private and public. And so, yeah, I’m thoroughly on board with reformed public theology.

Tooley: Matthew Kaemingk pointed out, though it’s obvious to you, that many Christian traditions, or many trends in American Christian thought, emphasize entirely resistance to power and opposing “the empire,” which is a very truncated view of Christian vocation in the world.

LiVecche: Yeah, that’s right, and there’s one question that I had with that that I would love to follow up, and maybe you know something about it. He somewhat discouragingly said that in reformed public theology, because reformed public theology recognizes that the arts and the sciences and economics and all these different spheres might have something to say about truth in the world; therefore, theology isn’t the queen of the sciences. And I found that phrase interesting, because theology as queen of the sciences could certainly be abused, but the idea of theology as the Regina scientiarum goes all the way back to the Medieval Ages. And I don’t think it was ever intended to be solitary and sort of like only theology has something to say about truth, but it was the idea that, as we look at all these other, science in a sense is anything that helps us to understand the temporal world. And theology simply stands, the worldview simply stands, in the primal place from which we view these other things. And so, maybe it doesn’t have a final say or anything like that, not an exclusive right to dictate what truth is, but I was just intrigued by that. If there’s a deeper history in how the phrase, or theology, is the queen of the sciences has been understood that needs to be reformed. I simply don’t know that. I’ve always considered, back in Slovakia when I helped run a study center, we used to lament that theology used to be the queen of the sciences and now it’s just the bastard child of philosophy. But I’m open to knowing another history of it.

Tooley: Yes, I was curious by his use of that phrase. So, you and I both will have to study his book in greater detail. Finally, Marc, moving on to the anniversaries regarding the atomic blast in 1945 and Japan’s surrender, Providence hosted a conversation last night between you and our good friend and contributing editor Joe Capizzi at Catholic University on this topic, with you defending the US use of atomic weapons and Joe Capizzi, aligning with Catholic Church teaching, critical of the use of atomic weapons. Give us a little bit of a summary of that if you could. My impression was that you were coming from a Christian Realist perspective, as you should be, and Capizzia I think, and you were more focused on the practicality and the pragmatics of what were available to policymakers in August 1945; Joe Capizzi was more focused on the abstract thought of Catholic teaching and the moral absolutes that go along with that. But your thoughts?

LiVecche: Yeah, I think that’s right. Joe and I have gone around on this now a number of times, both privately and publicly, and we probably still need to continue to do so, because I think we’re saying much more than simply something about Hiroshima. Hiroshima has become, in one sense, the case study for two different ways of viewing what it means to act morally in a world in which sin is a stark reality. And I can lay out the history of Hiroshima, of leading up to the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima, which is what I do, and I say, given that history and given the available options at the time, acknowledging that all we’re doing there is trying to understand circumstances on the ground to the degree that we’re able. Recognizing we don’t have omniscience, so we might be getting these details wrong, but recognizing that, nevertheless, we have to act. And because we’re mortal beings, we’re free to act in different ways, and when we faced the question of dropping that bomb or pursuing an alternative, when you understand the choices that were available and the context of those choices, it becomes to me morally, frankly, self-evident at this point that the dropping of the bomb was the most moral thing that could have been done. Joe will approach all that, and he’ll push against some of the things that I perceive as fact, so that’s fine, but even if he were to concede the history, it would still be brought to the point where he’d say okay, all of that might be true, but the problem is dropping a bomb on a city full of at least partially innocent people is morally wrong. You simply can’t do that full stop. And now I don’t have to concern myself with other things that I’m not doing. All I know is that I can’t do this thing that must be done. And that is where I think more of the work has to be done, is trying to understand that dilemma, really perspective. To say when you’ve only got so many options, you have to act. You choose to do the greatest amount of good you can do. And it’s not a purely consequentialist argument where the numbers are the only thing that matter. I’m trying to make a moral case that we have reason to prefer other clusters of innocent lives that were in conflict with the innocent lives in Hiroshima, and that we have reason to prefer those other innocent lives. So, it’s one part a historic argument, but I think it’s much more about moral action, a theory of moral action, and how human beings have to act in the world. Questions of dirty hands comes into it. I’m trying to make a very strong case for Hiroshima that it’s not a matter of dirty hands in the sense that okay, it was a morally wrong thing to do, but it was the least morally wrong thing to do. I’m trying to say no, as counterintuitive as this seems, it was a moral thing. And to have done it did not morally stain us; to not have done it would have morally stained us. So, I’m trying to make a very strong claim. There are moderate views in between us, but I think that’s a kind of hashing out of the argument.

Tooley: Well, it was a spirited and intellectually, theologically deep conversation between you and Joe Capizzi. We’re posting a video and transcript today, so I hope our listeners will check it out and learn from it. And we’re concluding this episode of Marksism. Thank you, Marc LiVecche. Until next week, bye-bye.

LiVecche: It was a pleasure.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024