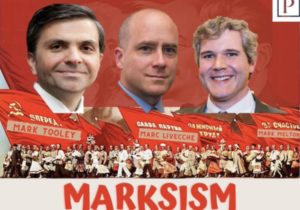

Providence editors Mark Tooley and Marc LiVecche from Christian Realist perspective discuss Alberto Fernandez’s piece on anti-dictatorship protests in Cuba, Alan Dowd’s and Marc’s pieces on US withdrawal from Afghanistan and Mark’s piece on providential optimism versus abstract optimism in global affairs.

Tooley: Hello this is Mark Tooley, editor of Providence: A Journal of Christianity & American Foreign Policy, with another episode of Marksism, with fellow editor and fellow Mark(c), Marc LiVecche. We will review three pieces from Providence over this past week. Firstly, a commentary by our contributor Alberto Fernandez about the crisis in Cuba and the ongoing resistance to the communist regime there. Secondly, Alan Dowd’s reflection on the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the potential calamity unfolding there. And then, finally, my own piece on history and so-called democratic piety. But starting with Cuba, Alberto Fernandez, himself of Cuban background, offers his sympathy and solidarity to those in Cuba who, having lived under over 60 years of one-party totalitarian rule, are ready for freedom and demonstrating in the streets. Alberto, who himself has been very involved in US communications and efforts to disseminate accurate journalism and reporting in closed societies, effectively warns against exaggerating our own powers and capacities to help the Cuban people overthrow their regime. In fact, the US cannot do what they need and they must do it for themselves. So, certainly we do offer our moral and spiritual support, but it’s unrealistic to go beyond that. So, Marc LiVecche, Christian realist, what say you?

LiVecche: Yeah, I think that’s right. I think that’s the maybe harder edge of being a Christian realist, right, is the sober-minded acknowledgement that there’s only so much you can do sometimes. To say there’s only so much you can do, it needs to be emphasized, is not to say that there’s nothing you can do. Sometimes those things that we do that feel inadequate, like simply telling the stories and accurately reflecting on what’s happening on the ground, broadcasting the conditions that the Cuban people face. Sometimes it feels very inadequate; it feels very limited, but sometimes that’s very significant. As Alberto says, if the Cuban people can recognize genuine American solidarity, that pays dividends in ways that probably most Americans can’t really appreciate. But I think that the telling is in some of the images that are coming out of Cuba, where you see US flag-waving Cubans marching for their own freedoms. And many of us, especially in this Olympics year with a lot of the stories coming out about Olympic protesters, we forget the symbol of the flag and the powerful symbolism that much of the rest of the world sees in it. And so, if that’s the case on the ground in Cuba, then we can ratify some of that symbolism by, as you said, our own spiritual solidarity with them. Telling the stories; telling them accurately, not forgetting what is there, putting pressure on our own government not to reward the Cuban Government by lifting embargoes, and things like this. It’s limited, it’s frustrating, and we should find it dissatisfying, but it is a realist perspective to recognize there’s only so much you can do.

Tooley: Speaking of realism, looking at Afghanistan, our contributor Alan Dowd laments the unfolding tragedy there as US troops withdraw and the Taliban seemingly advances, with the Afghan government appearing feckless and many of our allies facing dark futures. So, Alan laments this unfolding drama that seems to repeat what happened in South Vietnam in the early and mid-1970s as the US withdrew there and the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong defeated, conquered, and killed many of our allies. Alan does not offer any alternative constructive proposals, and those who favor full US withdrawal of course point out that having invested so many American lives and hundreds of billions of dollars, the Afghan government still appears unable to defend itself against the Taliban. Perhaps our presence and our subsidies have been unhelpful on some level, but Marc LiVecche, what say you? What’s the Christian realist perspective on the unfolding horrors in Afghanistan?

LiVecche: The Christian realist perspective today seems to be grounded in frustration and never-ending impatience. I ended up writing my own piece that’s out this morning as well to dovetail with Alan Dowd’s. And I remind readers that Jean Elshtain saw in the then dropdown in Iraq similarities with Vietnam. And she critiqued the Vietnam War, and she feels those critiques were correct, but she says alongside those critiques we also have to remember the local people. And the thousands that, as she says, we abandoned and left behind to prison, to concentration camps, to execution and all of that, and she feared that we might do the same thing in Iraq and counseled against it. What we draw out of that is the recognition that, at the very least, one has to leave with honor, which means not leaving behind our friends. And there are things we can do, and the Biden Administration has demonstrated a willingness and is apparently planning by the end of July or early August to begin evacuation flights of interpreters and others that have helped US operations there, including their families. Some people are doubtful at the ability of the administration to put something together quickly; some have suggested, I have linked articles that suggest, there’s no real plan in place. And so, they’re questioning whether or not we’ll be able to do it. I think what is telling is that Biden is making plans to get the interpreters out, while at the same time suggesting that it’s highly doubtful that the Taliban will take over all of Afghanistan. He says that the current government in Afghanistan has the capacity to provide human security, but apparently, he doubts at least their willingness to if he’s planning on rescuing all the interpreters. One wonders why he thinks that evacuation is necessary if he’s so optimistic about the ability of the government to contain the Taliban. So, I think Dowd’s dire predictions are probably the predictions most people have. What we can do now? As a Christian realist, I don’t know. You read a lot of Paul Miller’s stuff for the last twelve years; he has been lamenting the United States not doing the right things from the early footprint of the Bush Administration to the Bush Administration’s recognition that actually they had to do more than simply killing bad guys and counterterrorism and do something like state building, not democracy building necessarily, but at least putting in place an apparatus for basic human security. You know, grounded in democratic principles and human rights principles, but recognizing, as Elshtain always recognized, that you need basic human security in order to prevent worst things from happening. And that’s not a purely idealistic emphasis, it’s a very realist emphasis that says the external perimeter of US security is stabilized when places like Afghanistan are themselves stabilized, and that just comes from being a minimally decent state. We need to help the Afghan government provide basic security, and there’s indications that that will still be done. We might provide satellite imagery to Afghan troops on the ground and other means of support, and one hopes so, because it doesn’t appear right now that anybody really believes that the Taliban can be kept at bay. And that will be a human disaster that we should avoid. I know the US has paid enormous costs, but so have the Afghan people, and they will continue to pay them. We need to demonstrate to the world that the US is a friend and there’s no better friend, but that will be hard to defend if we abandon the people that are there.

Tooley: And finally, my piece on history and democratic piety. I’m responding to two writers at a podcast, or blog, called “Wisdom of Crowds,” one of whom is Damir Marusic, who is a steely realist and laments the proclivity of Americans and Westerners who are idealist to just assume that democracy and human rights will prevail throughout the world and that malefactors will be punished by the judgments of history. He quotes Martin Luther King’s famous confident exclamation that the arc of history bends towards justice. Damir Marusic counters it with a quote from Machiavelli that says in the end it’s about who wins, not who is more just. And I also respond to another writer at that blog who complains about the assumption that there’s an ongoing judgment against democratic regimes held to a higher standard, whereas repressive regimes seem to be held outside that standard, which I don’t think is a quite accurate perception of where democratic idealists are. I counter in defensive of Martin Luther King, who was not an idealist, but I believe a providentialist, who believed that it was not just the automatic forces of history, but rather the judgments of the deity himself that ensure justice does in fact prevail on earth in the end, but it is not achieved or enacted passively. And in fact, that arc towards justice is littered with martyrdom and much human suffering, of course embodied in MLK’s own life. So, I propose that, yes, Americans, Christians, and all who believe in democracy should have a providential confidence that those regimes that respect human dignity and human rights do have not just a moral upper hand but the historical upper hand, and we will prevail in the end. Not through passivity, but rather through a robust defense of our societies and our democratic institutions. Marc LiVecche, your response?

LiVecche: In a nutshell, do no harm, help where you can, do the good that you are able. That is the bottom line to Christian Realism. That requires sober-minded realism, and that acknowledges that arcs do bend but they have to be helped to bend. So, I think your push back was well done.

Tooley: I always appreciate compliments from fellow Mark(c), Marc LiVecche, and appreciate this episode of Marksism. We’re sadly lacking the third Mark(c), Mark Melton, who will rejoin us next week. Until then, bye-bye.