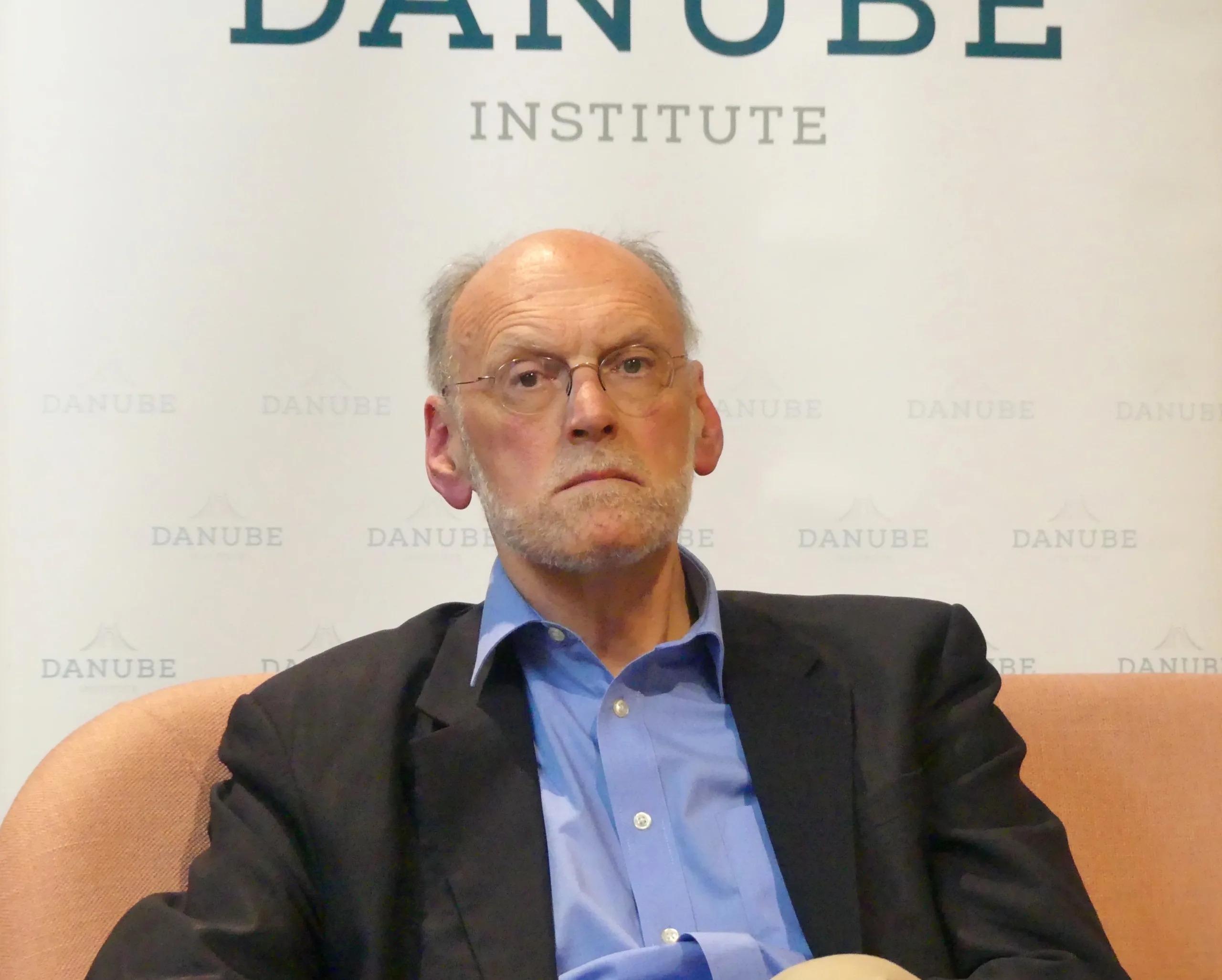

Nigel Biggar speaks with Mark Tooley about his new book, What’s Wrong with Rights?

Tooley: Hello this is Mark Tooley, editor of Providence: A Journal of Christianity & American Foreign Policy, with the honor of interviewing Nigel Biggar today, a sometimes contributor to Providence, perhaps best known as the world’s most renowned scholar of Just War teaching. He’s at Oxford in England and has a new book on the origin and meaning of human rights called What’s Wrong with Rights, if I recall the title correctly.

Biggar: That’s right.

Tooley: And so, Nigel, it’s a pleasure to talk with you, and please tell us a little bit about your book and why you wrote it.

Biggar: Thanks, Mark, and thanks for the opportunity to talk about the book. So, the title is What’s Wrong with Rights, but the title does have a question mark at the end of it. I was stimulated to write it for a number of different reasons, but one of them was that in Christian circles, there is the view that there’s something problematic about the very concept of a right as a property of an individual. So, you’ll find people like Alasdair MacIntyre, the Catholic philosopher, and Joan Lockwood O’Donovan, the Anglican theologian, arguing that the very concept of a right as the property of an individual is radically individualist. That it’s contrary to any notions of common good. That it corrodes common good, and that it is therefore actually unchristian. And, in fact, O’Donovan argues that it’s kind of irredeemably tied to a radical Hobbesian amoral conception and it can’t be redeemed. So, I wanted to explore how far that’s true, and that was one of the stimuluses for writing it. Another provocation was just observing that in public discourse, certainly in my own country in Britain, but I think in the US as well, that public discourse is very happy talking about rights, but very reluctant and shy to talk about morality. So, lots of rights talk in public, not too much duty talk or virtue talk. And, as a Christian, aware that duty talk and virtue talk is very familiar to Christians and has been from the beginning, rights talk is relatively novel. So, as a Christian, observing that feature of our contemporary public discourse is very striking and raises questions.

Tooley: Now the concept of human rights, is it intrinsically rooted in Jewish and Christian teaching or not necessarily?

Biggar: Not necessarily. The concept or rights, of something being all things instead of morally right, of there being an objective moral order, is certainly rooted in Jewish and Christian tradition. And the concept of illegal right, that’s the say some kind of privilege or freedom or benefits that’s granted by a particular legal system, that comes into discussion in the West in about the 13th century, as well as talk about natural rights. But that’s the talk about natural rights, and legal rights is relatively late. So, for example, I mean, you mentioned, Mark, that I have done some work on the ethics of Just War. In Christian Just War thinking, the concept of a right doesn’t appear at all. There’s lots of talk about the duties of soldiers and the virtues of soldiers, but no talk of a right. Now this is controversial, I mean, you’ll find people like Nick Wolterstorff will argue that the, if not the word, the concept is implicit in the Bible. And John Witte will argue that the concept of a right goes way back. I’m not so sure. I think it’s a relatively, it’s a medieval development. Yeah.

Tooley: And obviously, the concept of rights in the contemporary world, it’s been virtually universalized. Everyone accepts rights. But so many misunderstandings about what rights are and should be, what are the greatest misunderstandings in the world, or at least in Western civilization, today about rights?

Biggar: Well, I can think of a couple of them. So, a couple of things that are wrong with rights, but let me preface that by saying first of all what’s right about rights. Just so that people don’t think I’m being entirely negative about rights. I’m not. And the first thing I say in the conclusion is that a legal right is, let’s say to it to liberty or to some kind of benefit, that is a good thing. That’s to say if a society decides to ground a legal right, what it’s doing is to say that an individual’s access to this freedom or this benefit is supported by social institutions. Whether it’s social opinion, whether it’s the police, whether it’s the courts, so that if my rights to something is threatened or violated, a society in one way or another will come to my support. So, a right strengthens my claim to something that’s worthwhile, whether it’s a claim against being arbitrarily arrested or it’s a claim to welfare benefit, and there’s no get into that at all. So, a legal right that a society decides to grant is a perfectly good thing. So, back to your question, what are some problems? Well, one problem is when people absolutize rights and forget whether or not it makes sense for a society to ground a right depends on circumstances. Not all rights can a society afford. A society can’t afford to grant the same degree of security to right. So, for example, here in the West in normal circumstances, if you’re accused of some criminal act and taken to court, then we regard as part of a fair trial that you will have access to legal counsel. And that is a special guard against your being falsely convicted, that you have access to legal counsel. That’s good. But in Rwanda in the late 1990s after the genocide, there were tens of thousands of people languishing in prisons designed for about 12,000, and some of them were dying, they couldn’t process the cases fast enough because there were no lawyers because the lawyers had fled or been murdered. And what they decided to do was to adopt a more traditional way of processing cases. And this did not involve lawyers. So, those accused did not have access to legal defense. There are other ways in which there were safeguards against false conviction, but not as secure as we have in the West. But the point is in Rwanda that they could not afford anything else. Nevertheless, human rights advocates complained bitterly to the Rwandan government that they were violating the human right to a fair trial. The human rights advocates simply could not take into account the fact that the circumstances prevailing in Rwanda at the end of the ‘90s and early ‘00s didn’t allow for the provision of legal counsel. So, Rwandans accused of genocide had access to a fair trial, but the fairness of the trial was not as secure as we are used to because of the conditions in which they were operating. And that isn’t ideal, but we need to recognize that sometimes conditions are not ideal. And those of us who care about rights need to be careful not to, as it were, devalue the currency by making impossible demands. So, that’s one problem. Another problem is that when I assert my right, yes, it does imply that you have a certain duty toward me as a right holder. So, rights do imply duties. But what that conception misses out is the fact that I, as a right holder, may be, an indeed am, subject to duties and obligations that govern how I should exercise my right. So, I may have a right, but as a Christian, I am bound to exercise that right charitably. And it might even be that the obligation of charity means that in this case, I do not exercise my right. And it’s that notion of obligation and duty that is generated by a larger moral order or context that impinges on the right holder that is often missing from public discourse. So, those are a couple of things that can go wrong not with the concept of a right, but with the way in which we talked about them.

Tooley: Now, in America, and I’m sure in Britain, there is great confusion over categories of rights. So, I have a right to freedom of speech versus I have a right to a fully paid for college education versus I have a right to have my perceived gender identity fully affirmed by society and the government. So, how do you respond to these various claims and categories of rights?

Biggar: Well, just to take the last one first, a society can grant such a right. And in my own country, there have been moves in England, and there are still moves in Scotland, to give people the right to have whatever legal gender they fancy. I myself think that is crazy and lots of other people do too, but we could do that, it’s just from my point of view a crazy thing to do. So, some rights can be granted, but they just don’t make sense or are a bad idea. A right to college education. Again, if your society or my society is wealthy enough to grant such a right, then we can do it. We just need to remember there are some societies that can’t afford it. We also need to remember that if we grant everybody a right to a college education, the amount of public money, because rights cost, right. So, if you give someone a right to a college education, it means presumably someone’s got to pay for it, presumably the state. If the state’s paying for your college education because you have a right to it, then the state is not paying for something else, or the state is raising your taxes. So, again, remember rights cost. And therefore, rights are conditional upon the resources a society has. And as for right to free speech, again, that doesn’t cost so much. I guess except insofar as the state might have to deploy police or courts to enforce the right if it’s infringed, it doesn’t cost so much. But one thing I’d say to that is, it’s good that we have a right to free speech. But here’s where a Christian conception bears on the matter. Yes, I have a right to free speech. But if I abuse that right by speaking freely in an insulting, gratuitous, cruel, provocative, demeaning way within the law, let’s suppose I do all those things without quite infringing hate speech or whatever it is the laws against hate speech, if I abuse my rights, I will provoke other people to violate my right. And I might actually be in the right into disrepute. And besides, if I’m abusive in my use of the freedom of free speech, I can create a very hostile, conflicted, disturbed social environment. So, by all means let’s affirm the right to free speech, but let’s remember the moral duty to use it well. And I think in a liberal society and in a post-Christian society that, as I said earlier, may not be terribly sure about what are the things morally to think, Christians have a major contribution to make. Because the kind of thing I’ve just said now, Mark, in terms of the need to use freedom of speech morally and well, charitably with restraint, even non-Christians can understand the social good that it is. And I think we need to give Christians and Jews and others who come out of a tradition that is confident in the notion of a moral order, we need to give other people the courage and the confidence to take that seriously.

Tooley: Well, on that point, Nigel, of course you’re ordained in the Church of England, and you’re a theologian. The concept of rights, explaining it or discussing it among Christians or other monotheists, that each person is created by God and bears his image, therefore, there are certain assumptions about how that person must be treated. But in a more secular society or a secular arising society where that assumption is not necessarily assumed, but yet the legacy of human rights endures remarkably, how do religious believers explain the imperative of rights to a non-believer in that society?

Biggar: Well, I mean, you’re correct in saying that Jews and Christians, with the view of God, of a benevolent God, and of human beings made in God’s image, we do have a very exalted view of human being and human dignity. Now, although that vision of human dignity comes attenuated or weakened in a society that doesn’t have the theological framework, there are still, what shall we say, there are still kind of vestiges of the notion in the wider public. People may not know quite how to justify and make sense of human dignity, and indeed it’s quite hard to outside of a theological framework, but the notion of human dignity does have purchase, does it not? And we can argue about its basis and, ultimately, what kind of context makes sense of it. But I think it still has, the notion of human dignity does have purchase. And we can, those of us who are religious can as it were build on that, because it is something people often understand. The danger is, of course, when rights become more and more cut loose from a notion of human dignity, they simply become instruments for individual egos to assert themselves and therefore to abuse their rights. And the danger there is that the whole notion then comes into ill repute, and people who behave that way are actually jeopardizing a society that recognizes rights. And so, and you can argue in favor of human dignity, I would also just point out that some of the implications of the concept of human rights that are cut loose from a notion of human dignity.

Tooley: Then finally, Nigel, do you think that, is it chauvinistic to say, or is it historically accurate to say, that the Anglo-American political and legal tradition has a very special focus on human rights that is unique and that merits, I suppose, special attention and nourishing in that our culture and nations have a special role in showcasing and advocating for human rights around the world?

Biggar: I think so. Before I talk about Anglo-American, let me talk about the West. It does seem as if the West, the Christian West, has generated a strong notion of human rights. In my book, there’s a chapter where I discuss how true that is. What we claim are human rights are actually, as some in the non-Western world say, these aren’t actually universal human rights, their Western rights, and they’re being imposed on us in a kind of imperialist fashion. And I explore how true that is. And I think it’s not true. I think you will find rights in every society, different as it were packages of rights and rights that are secured more or less strongly, but you’ll find the notion of a right in every society. But there’s no doubt that the strong and prominent notion of human rights is much stronger in Western tradition. As for Anglo-America, well, yes, I think the tradition is even stronger there insofar as in England and then America, we did develop and generate legal rights as ways of limiting the state or limiting absolute executive power. And so, that tradition of the limitation, the constitutional, legal limitation of executive power, is very strong in the Anglo-American liberal tradition. To some extent the rest of Europe borrowed that from us in the 19th century. And through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it’s become universalized. But yes, I think that Anglo-America has had a special tradition of rights that limit executive power, and, yes, we do have a special responsibility in the present world to uphold and promote, as far as we can, human rights. Particularly since there are certain very influential countries, not least China, where, in spite of rights being legally enshrined, the practical respect for them, as we’ve seen in Hong Kong, is not so great. So, I agree with you, I think we do have a special responsibility to uphold rights worldwide.

Tooley: Nigel, could you hold up your book again? Nigel Biggar, author of What’s Wrong with Rights, thank you for a very enjoyable conversation.

Biggar: Thanks for the opportunity, Mark.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024