At the Christianity and National Security Conference in Washington, DC, in October 2021, Jennifer Patterson talked about the social dimensions of religious freedom and public diplomacy. She made the case that “the character of our culture determines our capacity to lead on the world stage.” Patterson also discussed soft power elements of US foreign power as well as how the US communicates with foreign governments and publics. She said, “There should be a coherence between US foreign policy and the principles, institutions, ideals, and constitutional order that that foreign policy exists to defend.” Then she talked about two principles and their intersection with US foreign policy, particularly public diplomacy: religious freedom and respect for life.

Rough Transcript

Mark Tooley: Thank you all, you’ve been an excellent audience. We have three more excellent speakers before the afternoon is over, the next of whom is Jennifer Marshall Patterson, who teaches at Reformed Theological Seminary and is also a fellow at the Heritage Foundation here in D.C. I cannot help but boast that Providence is claiming credit for her marriage to Dr. Patterson in that they were both speakers at our first Christianity and National Security conference and both went to dinner with us afterwards (Marc LiVecche: With my prompting!). Yes, Marc LiVecche wants his share of the credit, but we are collectively claiming at least some credit. So thank you Jennifer for joining us.

[Applause]

Patterson: Well thank you Mark and thanks all of you for being here. You never know what will happen at a Providence conference, so you’re glad you came. I’m going to continue in this cultural vein that Paul Marshall led us on during this last session, but I’m going to turn the focus to us domestically in the United States, and I’ve always been interested in the intersection between domestic and foreign policy. That’s because I’m going to argue that the character of our culture determines our capacity to lead on the world stage. We need more people who understand that intersection between the character of our culture and our capacity to lead on the world stage. And so I hope if some of the themes that I bring up today are interesting to you, you may be thinking about career tracks that would help you engage on these important issues in the future. As has been mentioned, scholars typically talk about four instruments of national power, known as the acronym “DIME”: diplomacy, information, military, and economics. And my talk is going to focus primarily on those first two, diplomacy and information, a little bit on economics. But we’re talking about the soft power elements and how the U.S. communicates both to foreign governments and to foreign publics, foreign populations, as well as how we use resources abroad, a bit about that as well.

Well there are many debates about foreign policy and international theory, and you’re going to hear some of them here during the next 24 hours, but I want to state something from the outset that shouldn’t be controversial at all. And that is that U.S. foreign policy defends the United States, its institutions, and its ideals. And that’s just extremely basic. And this suggests another simple idea: There should be a coherence between U.S. foreign policy and the principles, institutions, ideals, and the constitutional order that that foreign policy exists to defend. Now you may be gathering by the fact that I’m raising these very, very simple and basic statements that I discerned some confusion and some lack of coherence between these things. We live in a world where there will always be conflicts of ideas and values among the nations, and that means that those representing the United States need to be clear about this country’s political order and its ideals. In other words, we need to know and we need our leaders to know what we stand for. But here’s the challenge and really the great blessing for the U.S. in the global battle of ideas: We live in a free society, and in a free society we the people are the keepers of the ideas and the institutions for which this country stands. If our founding principles and the constitutional order designed to safeguard them are going to be maintained, it is the American people and the government we authorize who will be the ones maintaining that. The situation is, of course, much different in authoritarian regimes where the national purpose and meaning are simply enforced by the regime. Everyone was extremely clear this summer what a Taliban-led Afghanistan would stand for. And the reality is much different in a free society, thankfully, but it also means that we have particular responsibility. Our ideas and institutions, our national self-concept, are constantly up for debate, and therefore they’re more vulnerable to erosion in terms of their purpose and meaning. And it takes work to maintain them, work that needs to be done by those leaders in domestic policy as well as leaders in foreign policy and national security. And increasingly, I want to argue we should think about leadership that straddles those two and thinks about the ways that issues translate between them.

So today I’d like to focus on two particular principles and their intersection with specific areas of foreign policy. The first is religious freedom and how it intersects with our overall classic diplomacy, as well as public diplomacy in particular. And then respect for life and how that is protected or not protected in aspects of our foreign aid and in multilateral institutions like the UN and its satellite organizations. So let me begin with overall foreign policy and religious freedom. Regrettably, today the role of religion and religious freedom and religious practice in the American order are poorly understood, and that’s particularly true of policymakers and perhaps even more true of foreign policy leaders. One reason for that is that the idea of strict separation of church and state has become very prevalent in the last half century, and this outlook has led to the idea that government has nothing whatsoever to do with religion. It encourages the view that religion is personal and private, irrelevant to public policy, and should be out of the public square. A second reason for lack of policymakers understanding about the significance of religion is the assumption that political and social progress, we were told by the experts, would increasingly marginalize religion. But that’s not what the data have suggested, whether about here in the United States or abroad. Those who do not understand religion’s continued relevance in our own society are very likely going to overlook religion’s influence abroad. If policymakers approach foreign affairs from a merely materialistic mindset, if they’re unfamiliar with a religious framework for interpreting human action and human motivation, they’re going to lack important tools for assessing and engaging effectively with highly religious populations around the world.

Well, policymakers have noticed some of the problems with the realities I’ve just described, and 23 years ago today, on October 28th, President Clinton signed the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998. Congress had passed the law by overwhelming majorities, and the purpose of the law, the International Religious Freedom Act, was to commit the United States to a strategic framework for advancing religious freedom around the globe. Here’s what it did, five things: It created the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, known as USCIRF, which was an independent body of citizens working outside of government. And USCIRF’s task is to make recommendations to the President and to Congress regarding the status of religious freedom around the world. The second thing that the International Religious Freedom Act, IRF Act did was to create an Office of International Religious Freedom at the U.S. State Department and to put an Ambassador At-Large for Religious Freedom in charge of that office. Its purpose was to integrate religious freedom into the strategic priorities of our national security and foreign policy apparatus. The third thing that the IRF Act did was to mandate that this State Department Office for Religious Freedom produce an annual report on all the countries of the world and how religious freedom fared in each of them. Fourth, the law gave Congress and U.S. agencies a wide range of options for the government to address violations of religious freedom around the globe, and that included in particular the denotation of Countries of Particular Concern, CPCs. These are countries like Iran and North Korea who are frequent offenders, consistent offenders, violating to the extreme religious freedom. And a fifth item that the International Religious Freedom Act did was to call for training for U.S. diplomats in the area of religious freedom.

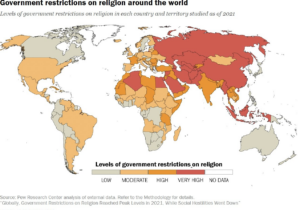

Well the decades went by, and as of 2016, there was insufficient progress towards some of these goals. So there was an update to the law, reauthorization of the law, that brought about some more particular changes. For one thing, the Ambassador At-Large was now going to report directly to the Secretary of State, and as you can imagine, that would create a higher profile for this portfolio in the State Department, in the building. Second, international religious freedom training was mandated for all foreign service officers, so that those who go abroad, those who are representing the United States, understand and can represent well what we stand for in terms of religious freedom. And third, the reauthorization in 2016 added a category of Entities of Particular Concern. Countries of Particular Concern had been the previous 1998 version; Entities of Particular Concern was the new statement. And you can imagine what kinds of eventualities that was trying to cover the kinds of non-state actors, individual actors, who could also be very egregious violators of religious freedom. Well the need is very serious for this framework because 80 percent of the people in the world live in countries where religious freedom is severely restricted, and they’re suffering from persecution from two directions. The first is government restrictions on religion, and the second is social repression of religion. This may be where a religious majority inflicts harm on religious minorities at a social level between private citizens or groups and the government turns a blind eye, does nothing about it. So government restrictions and social hostilities towards religious minorities are both problems of religious persecution around the globe.

What has been the impact of the International Religious Freedom Act? First, U.S. leadership in this area, the creation of institutional framework to address it, has been an example to other countries. The UK, Canada, the EU have all created special envoys for international religious freedom. As for stopping religious persecution, there have been some minor successes over the years, and these have been attributed mostly to high level pressure, presidential pressure in particular, on behalf of specific prisoners of conscience. So you can think back to the example of President Obama and his weighing in for the release of Pastor Saeed Abedini from Iran. President Trump did the same for Pastor Andrew Brunson from Turkey. So we’ve had these high profile cases, but now we are 20 years and more out from the original passage of the International Religious Freedom Act, and it is time to ask how well its goals have been integrated into foreign policy generally. And here we need to do better. We need better integration of the Ambassador and the Office into the overall policy-making functions of the State Department. To date most of what the Office has done is to be an important watchdog and monitor with regard to human rights, but U.S. foreign policy should rely more on the strategic insights of the personnel of this office. The work of the International Religious Freedom Office should also be better connected to public diplomacy efforts.

And let me turn to public diplomacy now. As you know, the kind of textbook definition of public diplomacy is to help foreign audiences gain an understanding and an appreciation of American ideals, principles, institutions, and policy. This means that U.S. public diplomacy needs to be firmly grounded in those ideals and principles, and that includes a right understanding of principles concerning religion. The American model of religious liberty and the continued significance of religious practice in our nation are some of the defining attributes of this country. In fact, as the late philosopher Michael Novak taught us, these attributes are as important to what makes America what it is as our democratic political system or our free market economy. Religion has had a great influence on U.S. history. That’s true from our earliest settlements to the great social justice causes of the late 19th and again in the 20th centuries. Today, the vast majority of Americans would still say that religion is at least somewhat important to them. Faith-based organizations continue to be at the front of responding to great needs, whether they’re hurricanes or tsunamis or bringing evacuations out of Afghanistan. Religious liberty is an American success story that should be told around the world. Religious groups have helped to fortify the discipline of self-government, and these are lessons that need to be communicated to highly religious populations abroad.

So what does this mean for public diplomacy? Well for one thing, public diplomacy always wrestles with content as well as tools, and I’m making an argument that the message itself is even more critical than the modes and techniques for projecting it to the world. We live in a highly technological society and can get caught up in those things and forget about the message itself. We’ve also been swayed by the idea that popular aspects of our culture are the way to advertise. Rock and roll worked to get behind the Iron Curtain and project a particular image of the United States. That seemed to work and so pop culture – we may lean on and have been tempted in the past to lean on too much to do the work that needs to be done to communicate about America. But I’m going to argue that pop culture cannot do justice to American ideals in the fight against potent ideologies that present strong, coherent, and deeply misguided explanations of the nature and purpose of human existence. In other words, this war of ideas calls for stronger stuff than Coca-Cola and Lady Gaga. It requires a clear, compelling, coherent articulation of the principles and institutions that define the American order. And this is most particularly important for those for whom religion is an important and defining aspect of their worldview. U.S. public diplomacy must convey to majority religious communities that adopting a policy of religious freedom can be consistent with promoting a positive role for religion that includes freedom to express religious views in the public square. The U.S. model of religious liberty includes a favorable view of religious practice, both privately and in public, and this is in contrast to some of the aspects of the French laicite model of secularism. Far from privatizing or marginalizing religion, our model assumes that religious believers and institutions will take active roles in society, including engagement in the political process and formulation of public moral consensus. So U.S. public diplomacy should communicate the continued importance of religion and traditional values in American life. Most Americans continue to attach great significance to religious faith, practice, the institution of marriage, family life, and a morally supportive environment in which to raise children. These are values shared by many highly religious populations around the world.

Turning now to foreign aid, I want to look at a specific example of how U.S. assistance should be consistent with a respect for life. In our domestic politics we have a long-standing consensus that taxpayer money should not be used to fund abortion. It’s the Hyde Amendment that established this in law, and regrettably it’s under a great deal of attack in this particular Congress. Well the same principle was extended to the idea of U.S. tax dollars supporting abortion in other countries, a practice which the vast majority of Americans oppose. Back in 1984, President Reagan established an international policy to mirror what the Hyde Amendment did domestically for international affairs, and this was called the Mexico City Policy. What it did was to require foreign NGOs that receive money and funds from USAID or State Department family planning assistance to certify that they won’t perform or promote abortion as a method of family planning. This has served to make sure that funds wouldn’t subsidize abortion or be used for abortion advocacy abroad. Now it’s been upheld by every Republican president since Ronald Reagan, but overturned and reversed by every Democrat since then. President Trump, in true to that pattern, reinstated the policy and actually expanded it so that it applied to all funds supplied by all departments or agencies to family planning abroad. But the Biden administration has overturned that policy. Similarly the Trump administration determined that the United States would no longer fund the UNFPA, the UN agency for family planning, because of the repeated reports that it had been entangled in China’s brutal and cruel population control policies which include forced abortion, and the Biden administration reverses course on this as well. The United States should have a policy of contributing to global health while affirming life, and respect for life is one of the foundational values of our society that we should communicate.

And turning finally to multilateral institutions, and also with respect to this issue of life, we regularly hear about security issues at the UN, but what we don’t get as much information about is the constant current of progressive social policy-making that springs from the UN system. During the Clinton and Obama and now Biden administrations the U.S. has advocated for policy on social issues at the UN that has pressed a liberal ideology on more conservative countries around the world, and particularly developing countries. It’s important, obviously, that the United States stand for strong and sound policy at the UN, but it’s also important that the U.S. press for reforms to the UN bureaucracy, which inherently pushes this kind of agenda. One of the biggest problems in this regard are the UN’s system of treaty-monitoring bodies. These treaty bodies are like standing committees, and they’re supposed to monitor implementation of UN treaties by member states. They have the authority to issue comments and clarifications on what is in the treaty, the convention, but in reality they go well beyond the scope of the actual text of these international documents. For example, treaty-monitoring bodies have used language about sexual and reproductive health to advance a right to abortion in international law, and they have pressed countries to liberalize abortion laws and weaken conscience protections for doctors. Even the U.S. has been excoriated in these forums for the number of pro-life laws that we have at the state level in our country. The threat here is that UN treaty body comments become a reference point for future recommendations and judgments made by international bodies. And while the treaty body comments are not legally binding, they are frequently referenced as customary international law, so U.S. leaders have every reason to be a strong voice for the protection of life and religious liberty and family and marriage at the UN. That will require restoring a focus at the UN to fundamental human rights, those that are enumerated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and promoting reforms to the bureaucracy itself that is perpetuating values and principles that go beyond the scope of agreed-upon treaties. There’s a feedback loop where progressive administrations domestically advance an agenda at the international level, establish a pattern there, and use it to reference back in our own legal decisions and decisions by our courts and by our legislatures.

So these are the several areas in which I wanted to give just a little bit of a snapshot of what it would look like to be attentive to some of the issues that we typically associate with domestic policy, but are very much in the battle of ideas at an international level in foreign policy, public diplomacy, foreign aid, and in our interactions in multilateral institutions. In closing, let me say that we need more people who are thinking about these issues and thinking about the intersection of them. I also like to emphasize to students who are thinking about their future that it’s critically important to think about the skill set that you want to exercise if you move into a policy arena. There is a particular skill set of being able to read the fine print of documents and bureaucratic jargon and so on. And some of the issues that I’ve touched on require that kind of a skill; it’s frequent as well in domestic policy in the areas of the welfare state and the health care system, the education system, where these very expansive arenas that have become very intertwined with our day-to-day lives. We need people who have a sound philosophy that’s consistent with our constitutional order and our founding principles to also be able to develop the aptitude and skills to read thousands of pages of code, which sounds undesirable but is critically important, and I hope that many of you will consider that for a future career. With that let me end and maybe take two or three questions in this remaining time.

Q: This question has a couple of assumptions, and if they’re wrong or you disagree go ahead and say that, but Eboo Patel is his interfaith leader that I’ve been listening to a lot recently. He talks about how religion is simply a conglomeration of your ultimate concerns. And I wondered, how do you have optimism that as a nation of religious liberty, where people have and frequently elect other people who have conflicting ultimate concerns, how can we exert enough political – leverage might be a loaded word – or just influence in an international spectrum, where there may be people who have a theology, whether it’s political or structured religion, that might be more cohesive or coherent based on a more authoritarian sort of state? How do we say and have hope that we can have that influence if we are conflicted inside ourselves by nature of our values of religious liberty?

Patterson: The question is how can we have hope of influencing the world for good on religious freedom if we are conflicted within our own context, and there are very authoritarian regimes who are quite sure of what they think on the international stage with respect to not embracing religious freedom. And so I appreciate the question because it gives me an opportunity to observe that there are very significant debates about religious freedom going on in our domestic context right now, and it is one of the reasons why those are so important, is because we are articulating that this is a freedom of all humanity, of all people under the sun, and to be able to communicate that abroad we need to be able to secure and maintain that religious freedom here. And I think one of the issues is we often get into a cycle in the United States, Paul Marshall was pointing out, that we don’t know our history well, and it requires knowing our history, knowing our principles on which we have formed a society, to be able to prize and maintain religious freedom, and too few young people are learning about that today. I hope you all are thinking about that; I hope you get some exposure beyond this talk to think about it here at this conference as well. I’ll point to the work of the Religious Freedom Institute, my husband’s organization, Eric Patterson, they have developed curriculum for teaching religious freedom with this very concern in mind, teaching the next generation to embrace the heritage and maintain the heritage that we’ve been handed down. It’s not a given and we cannot assume it.

Q: When we try and export religious freedom, how do we avoid making pariahs of the people we reach? You mentioned that they face a lot of religious persecution, not only from top down from the government but also from communities, so how do we promote not only decriminalization of the religious freedom but also its acceptance within other cultures?

Patterson: So the question is how – if we are reaching out and being advocates for religious freedom around the globe, as I interpret your question, it’s those who ally with us may face social hostilities from the religious majorities and that are not fans of religious freedom. And there’s been important work done, and housed again at the Religious Freedom Institute, the work of Brian Grim and others have documented that are trying to use evidence about human flourishing, social science evidence in particular, to demonstrate that it is in the interest of countries who are highly religious, it’s in the interest even of religious majorities to embrace religious freedom. The social harmony that that brings about is the surest way to secure the standing of beliefs, rather than hostility. So I’ll point to that body of work that has particularly thought about this question of how to do public diplomacy, particularly with religious majorities who might be hostile to religious freedom.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!