The following lecture was recorded during Providence’s 2017 Christianity and National Security Conference.

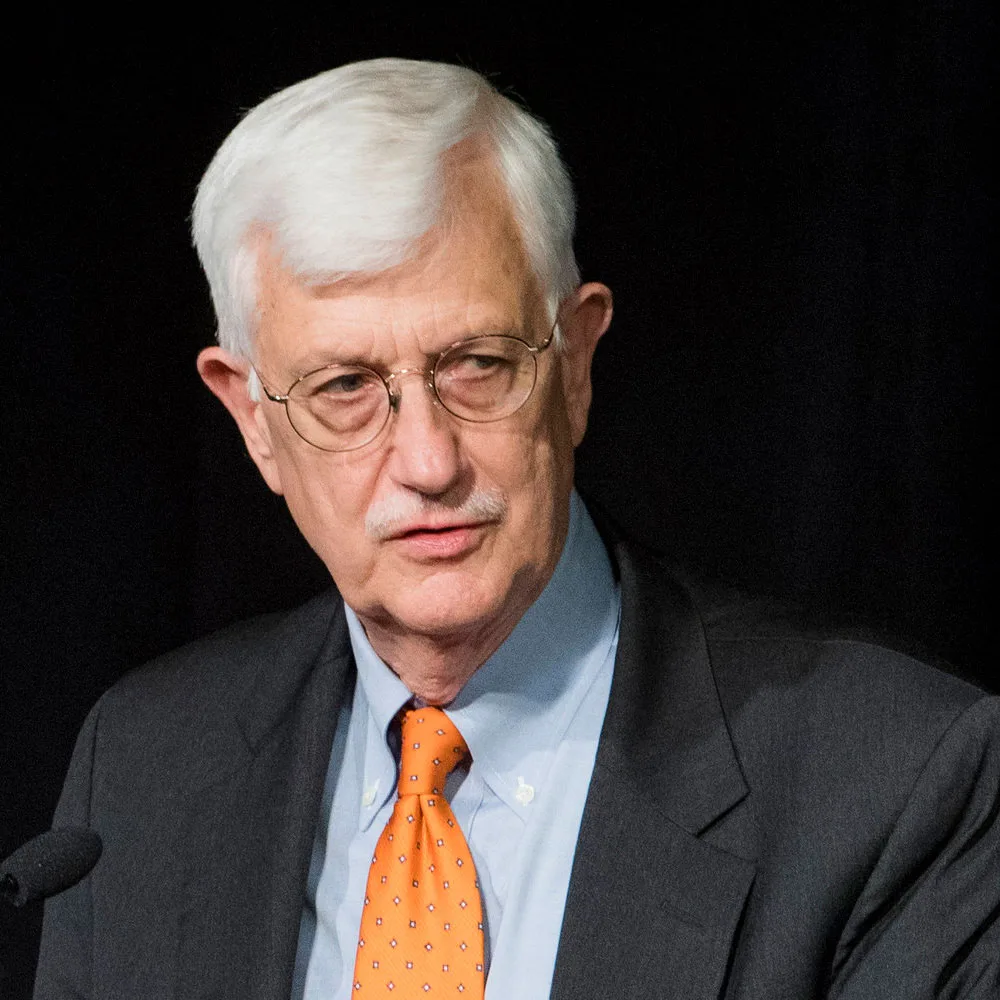

Thomas Farr argues that the most profound and powerful reasons for religious freedom are Christian reasons, and that they extend not only to Christians, but to all people. He discusses the roots of religious freedom in Christian theology and the importance of this theology today.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024