It’s Christmas Eve today and time for one of the oldest traditions in the blogosphere: the annual Via Meadia Yule Blog. Moving this year from The American Interest to Providence, the Yule Blog begins with an Advent blog on Christmas Eve and continues through the Twelve Days of Christmas to the Feast of the Epiphany. Updated every year, the Yule Blog aims to make the Christmas season merrier by exploring its meaning.

—

The stockings are hung by the chimney with care at the ancestral Mead mansion; and as I settle down for a long winter’s rest I am taking a break from politics and war, sort of, to yet another run of our good old fashioned Yuletide blog.

In particular, I want to blog about Christmas itself and what it means. Somehow my generation decided to leave this part out when we passed down the traditions and the lore we were taught to the next generation: We’ve bought a lot of Christmas presents, but we were too busy to think much about the meaning of the story or to teach the next generation much about this holiday and the religion that it defines. We did a great job teaching about Santa Claus and presents; nine in ten millennials celebrate Christmas. But, according to this 2015 Pew Poll, less than half of them think of it as, primarily, a religious festival.

That is where we went wrong. My generation and the generation before us inherited an enormous wealth of spiritual capital from a society shaped by hundreds of years of deep religious faith and engagement. Our environment was shaped by that wealth in ways that many of us did not understand; we took it for granted and, in too many cases, we neither looked deeply into these matters for ourselves or passed our grounding in the culture and faith of Christianity on down to our heirs.

That was a terrible and costly error; Christianity was and is the foundation of American liberty and democracy. Without the spiritual wealth that a deep engagement with the God of Abraham and the Son in whom he was fully revealed, our society will not long retain the trust, the honesty and the spiritual depth without which democracy and many other good things must fail.

In the 2016 election, American society had a little foretaste of what political life can look like when the virtues of humility, forbearance, honesty and tolerance begin to fade from our common life. Virtue is the secret lubricant that makes all our institutions work smoothly—and it is the secret glue that holds the social structures on which we all rely in place. The farther America moves from its rich heritage of faith, the less well America will work. This isn’t a partisan point. Christianity is the living force behind American liberal ideology as well as behind American conservatism. The values of honesty and tolerance in our national political life are ultimately grounded in the Christian faith that has formed the American conscience for hundreds of years. If we as a people walk away from that faith, the many blessings that it brought us will dry up and blow away. This isn’t a far-off danger; it is already happening. Year by year our politics become more contentious as the level of honesty and civility in politics decline. We’ve seen in 2017 how the absence of real faith and spiritual engagement in Hollywood, the media and political life leads to the objectification and exploitation of the weak. We’ve seen partisanship run amok, hatred take root, and corruption flourish. The farther Americans stray from the faith that formed us, the harder it becomes for us to maintain the republican and democratic institutions that give us both liberty and peace.

This is not to say by any means that only Christians are real Americans or good Americans. There have been and are today many great Americans who are not Christian, who are atheists, Muslims, agnostics, and Jews. But it is the Christian grounding of the American majority that has enabled this country to become the uniquely tolerant and accepting place that it is. An America that moves away from Christianity will be an America that ultimately moves away from tolerance, pluralism and respect for individual conscience. As I blog about Christ and Christianity, my hope is that this work will help create a more tolerant and accepting culture for those among us who seek God in other faith traditions, or who don’t believe in a personal God. At least for me, and I think for many other Christians, a personal faith in Christ makes it easier for me to honor and respect each person I encounter, regardless of religious, political or cultural difference.

In the old days, people kept a Yule log burning during the holiday season; at Via Meadia, we’ve had a tradition from the start of a festive Yule blog. From now until January 6, I’ll be Yule-blogging: reflecting on Christmas in ways that I hope will make sense to Christians and non-Christians alike. The Yule blog is a work in progress; each year I try to make it a little clearer, a little more useful, a little less hopelessly inadequate at explaining some of the most important and mysterious truths there are.

The meaning of Christmas is much bigger than the trite clichés that usually come up in this context; I won’t just be writing about the Importance of Giving and the Desirability of Being Nice. Christmas, at least the way I was taught, is a lot more than a merry interlude in the darkest, nastiest time of the year. It is more than getting or even giving. It is more than carols and candy, more than wonderful meals with the people you love best in the world. It is much more than the modern echo of the pagan festivities marking the winter solstice and the moment when the sun begins to reverse its long and slippery slide down the sky.

For Christians, 77 percent of the American people according to a recent Gallup poll, Christmas is the hinge of the world’s fate, the turning point of life. It is the most important thing that ever happened, or at least the beginning of it, and we celebrate it every year because it is still happening now. Whether we know it or not, whether we appreciate it or not, we are part of the Christmas Event that has turned history upside down. There’s a reason why we date the birth of Christ as the year 1 and why traditionally the world’s history was divided into BC, before Christ, and AD, anno domini, the year of the Lord.

Actually, as Pope Benedict XVI reminded us, the monk who tried to calculate it seems to have gotten it wrong; Jesus was probably born four to six years “BC.” He also did not know about the use of zero as a number; there is no Year Zero between AD and BC—which is why irritating pedants remind people at every turn of the century that the “real” new century or millennium doesn’t begin until 2001, for example, rather than on January 1, 2000. It’s also worth noting while correcting the math here that the Twelfth Night, traditionally celebrated on the evening of January 6, is actually the Thirteenth Night after Christmas itself. January 6 is its own, separate feast in the Christian calendar, the Feast of the Epiphany. I’ll get to it in due course, but that is why there are thirteen posts for the twelve days.

Superficially, Christmas is a simple and user-friendly holiday: presents, tree, more presents, food, mistletoe, deck the halls, and fa-la-la. How hard is that? But if you look beyond the commercial hype and the pop culture celebration, Christmas is a complicated festival that expresses some of the core beliefs that shape the identities and worldviews of about a third of the world’s people. Non-Christians, including the 5 percent of Americans who adhere to a non-Christian religion and the 18 percent who either claimed no religion at all or chose not to answer the pollsters, need to know about Christianity as much or perhaps even more as Christians do, simply in order to understand the cultural foundations of the society in which they live.

Religious education has pretty much fallen by the wayside in American life today. That’s a problem in more ways than one; I see the consequences all the time when students I teach—and policy makers and journalists I know—simply do not comprehend the cultural foundations of American politics and cannot understand the ways that so many people here and around the world are moved by religious values and ideas. I have taught a course on the relationship of American religious ideas to American foreign policy in some of our leading colleges, and I have had smart, well-traveled, and otherwise well-read students in that course who have never opened a Bible (or any other holy book) in their lives and simply had no idea why so many other people read and study sacred literature every day of their lives.

For Christians, I hope these blog posts will enrich your experience of this special season. To believe in the truth of the Christian religion and to encounter Jesus Christ as the saving Son of God is just the first step of a faith journey; deepening your faith through reflection and understanding, appreciating faith’s resonances and mysteries, participating in the communion of saints and God’s own life, joining the story and not just reading it: That is what being a Christian is about. A study of Christmas isn’t a bad place to start. The mysteries of the Christian faith are woven into the lessons, the carols, and the prayers of this special time.

I’m trying to blog as a vanilla Christian; that is, I’m trying to write about the elements of our faith that virtually all major Christian communities have historically shared. That puts me at odds with some of the more liberal trends in contemporary American mainline Protestantism; I think the historic statements of Christian doctrine as found in documents like the Nicene Creed make sense and give an accurate and compelling description of what it means to have a Christian faith. I’m an Anglican by conviction as well as by birth and that will inevitably influence the way I approach Christmas, but I won’t be trying to sneak in special little Anglican concepts here, and this won’t be about controversial ideas that divide Christians like infant baptism, predestination, the infallibility of scripture or, for that matter, the infallibility of the Pope. I hope that Christians of many denominations will find something here that captures what the holiday means to them, and that they will forgive any errors or misapprehensions on my part. These are deep waters, and even stronger swimmers than yours truly can be swept off course.

Final disclaimer: I’m not really qualified to do this. I’m not some kind of spotless saint who has achieved deep spiritual insight through a lifetime of asceticism, deep study, and constant prayer. Much of what I’ve learned about the right way to live has come through experiencing the consequence of doing things the wrong way first, and my knowledge of God, such as it is, is more the result of experiencing mercy and forgiveness than some kind of reward for living right. To make matters worse, I’m not trained: As a layman, I have no special theological training and don’t speak with any ecclesiastical authority whatever. If something in this blog troubles you, you should consult with experienced and thoughtful Christians whose lives inspire you, or the leaders of your own church. Christmas is big, and understanding it is hard.

You don’t have to know much about Christmas to know that there are twelve days of it; that song about the partridge and the pear tree has echoed through enough American shopping malls and elevators over the years that very few people haven’t gotten the message. Traditionally, the 12 days started on December 25, and the Christmas season ran for 12 days. The holiday celebrations ran on for one more day; the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6 marks the day when the three wise men arrived in Bethlehem with those gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

The association between the Feast of the Epiphany and the Twelve Days of Christmas remains strong. In much of the Spanish speaking world, January 6 is when kids get their presents. Jesus got gold, frankincense, and myrrh; they get video games and dolls. In New Orleans, January 6 marks the end of the season of Christmas holiday parties and feasting, and the start of the Carnival season of holiday parties and feasting. When I lived there, I remember people bitterly complaining about how unfair life was; while everyone else in the country was going on post-Christmas diets, the poor put-upon people in New Orleans still faced a month of king cake parties and packing on the pounds.

During the Christmas season, householders would keep the fires burning–necessarily so, as the Christmas season comes in the coldest and darkest time of year. The Yule Blog is a cyber-version of this old tradition, and we’ll keep it burning through January 6 with 14 posts (Christmas Eve, the Twelve Days of Christmas, and the Feast of the Epiphany) that introduce readers to the Christmas story and to the reasons that Christians think the story matters so much.

Christmas isn’t just the holiday that celebrates the birthday of the Founder of one of the world’s great religions. It’s the main reason so many of the world’s other great religions don’t like Christianity very much. Christians talk about that baby in the manger as God on earth. The monotheistic religions like Judaism and Islam find that idea blasphemous; polytheistic religions like Hinduism wonder why Christians think their own divine birth is so special when so many gods and goddesses have brought so many divine and semi-divine children into the world. Christmas, a holiday that popular culture romanticizes as a time of great peace, is one of the most divisive holidays on the world’s calendar. I want to blog about why.

Meanwhile, Merry Christmas to those of you inclined to celebrate that holiday, and seasonal greetings to everyone else. Whatever your faith or lack of it, however you understand the meaning and purpose of your life, may the next few days be a time of rest, relaxation, and healing reflection for you that brings you closer to those you love, more generous to those in need, and more in tune with that wiser, happier, richer, and more generous self that it’s your hope, your duty, and, with the help of a merciful God, your destiny to become.

—

Walter Russell Mead, a Providence contributing editor, is the James Clarke Chace Professor of Foreign Affairs and Humanities at Bard College, and a distinguished fellow at the Hudson Institute. He is the author of numerous books, including Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How it Changed the World. His next book, The Arc of A Covenant: The United States, Israel, and the Fate of the Jewish People will be published by Knopf in 2018.

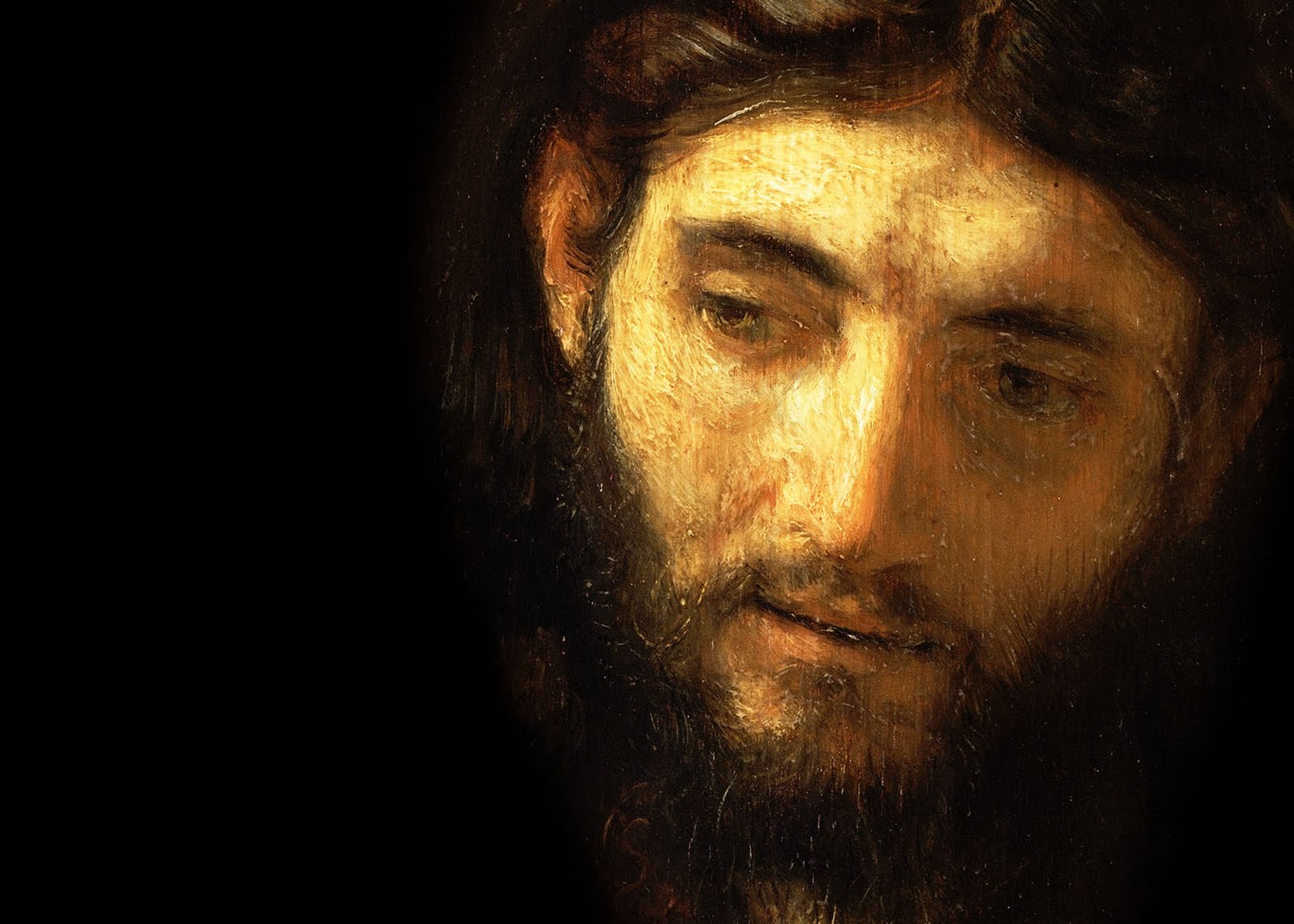

image: Angels Announcing the Birth of Christ to the Shepherds, 1639, Govert Flinck (1615-1660).

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024