The spread of Christianity in Korea and the city of Pyongyang, described in Part I, and the rise of Korean Christians as leaders of the Korean independence movement, described in Part II, were followed by the eradication of Christianity by the North Korean regime after 1945. The result was the end of “the Jerusalem of the East” and its replacement with the North Korean capital of today.

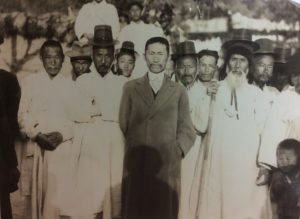

The half-century long presence of American Christians in Pyongyang and the Korean churches that they helped to found made Pyongyang a heavily Christian city at the time of the liberation of Korea in August 1945. The city’s population of 300,000 was approximately one-sixth Christian in 1945, and Christians were prominent among the Korean leaders who stepped forward to face the Soviet forces that arrived to occupy the city. When a Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence formed in Pyongyang, its leader was Cho Man Sik, a Presbyterian convert who had participated in the March First Movement against Imperial Japanese rule in 1919 and stayed in Korea after being released from prison a year later. At the age of 62, Cho had led nationalist activism in Korea for over three decades, influenced by Gandhi’s principles of non-violent resistance and economic self-sufficiency. In November 1945, he formed a political party called the Chosun Democratic Party to represent Koreans in Pyongyang and the north seeking an independent Korea under a democratic system, sought since the beginning of the 20th Century.

The Soviet authorities who ruled Korea north of the 38th Parallel installed a Korean Communist regime that could not allow any rivals to its authority exist, in part because of their lack of roots in the country. As described by Russian historian Andrei Lankov, whose education in the USSR gave him unusual insight and access to Soviet records, the Soviet political commissars commanding the occupation zone put into power a collection of exiles who had fought on the Chinese Communist side during the war, Russian-Koreans born and raised in the Soviet Union, and Koreans who had fought as guerillas in Manchuria and then fled to the Soviet Union.

Among the latter was Kim Il Sung, who had not been in Korea since 1920 at the age of eight. Raised in a Korean exile community in Manchuria, he had joined the Communist Party of China and fought in minor guerilla actions in China before taking refuge in the Soviet Union in 1940. There he became a junior officer in the Red Army, and after seeing no action during the war (aside from fathering a son named Yuri Kim, better known as Kim Jong Il, later his heir), he was sent to Korea in September 1945, a month after the Red Army occupied Pyongyang. This insecure new client regime had to eliminate home-grown rivals to its authority, and it did so with a rapidity and ruthlessness that exceeded similar Communist actions in Eastern Europe.

By the end of 1946, the Soviet authorities and their Korean Communist clients had eliminated practically all possible political and religious opposition. Red Army soldiers arrested Cho Man Sik in early January 1946 for opposing Soviet policies, and a purge of the Chosun Democratic Party soon followed, making it a leaderless entity following the regime’s orders. Suppression of the Presbyterian and Methodist churches founded by American Christians followed. The Soviet authorities had already excluded Korean Christian political parties in 1945, and in November 1946, its client regime created a state-controlled Federation of Churches that it required all church officials to join. Arrest and imprisonment was the fate of church leaders refusing to submit to state control, followed by confiscation of churches and church properties.

The nascent North Korean regime’s religious persecution caused numerous Christians to join masses of refugees who streamed across the 38th Parallel to seek new lives in the south, fleeing the new state’s oppression of Christians, landowners, business owners, and other class enemies. From 1945 to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, approximately 750,000 people fled to the south. Most crossed the 38th Parallel at Kaesong, once the site of a large Methodist mission, which became the official crossing point for refugees permitted to leave the Soviet occupation zone. Kaesong is best known today as the location of a special industrial zone in which South Korean companies are allowed to operate factories in North Korea, periodically closed in response to tensions between North Korea and South Korea.

The exodus continued during the Korean War as additional hundreds of thousands fled North Korea. Masses of refugees fled North Korea as a result of the regime taking its persecution of its own people to a new level during the war, massacring remaining Christians and other civilians that it perceived as enemies after its forces retreated following the Inchon landing in September 1950. Estimates of the number that escaped from North Korea in 1950-53 exceed 600,000, bringing the total since 1945 to approximately one-sixth of the north’s population of 9 million. The numbers of people who fled the North Korean regime exceed the worst estimates of North Korean military and civilian deaths in the Korean War, figures that Western apologists often cite to justify North Korea’s aggressive attitude and actions today.

North Korea’s efforts to eradicate Christianity in Pyongyang and elsewhere in its territory have been so ruthless and systematic that today few outside of Korea know that it was ever there, before the tyranny of the Kim Il Sung family. The Christians of North Korea have been a forgotten footnote to the broader flight of people from the north to the south, which itself has received little attention in the United States and other Western countries. As a result, reports of underground Christians in 21st Century North Korea, when noticed at all, generally are received as inexplicable oddities. They instead should be seen as remnants of a long-ago American presence in North Korea, which brought Christianity to a country where a Communist regime has spent over 70 years persecuting it out of existence. It has been perhaps the most thorough elimination of Christianity that has occurred in history, certainly in the 20th Century, and it is still ongoing now in North Korea.

—

Robert S. Kim is a lawyer who served as Deputy Treasury Attaché in Iraq in 2009-10.

Photo Credit: Mansudae Grand Monument in Pyongyang, North Korea. By Clay Gilliland, via Flickr.

—

Other Parts in the Series:

Part I: Jerusalem of the East: The American Christians of Pyongyang, 1895-1942

Part II: Christianity and the Korean Independence Movement, 1895-1945

Part IV will appear on Providence next week.

The story of the American Christians of North Korea and their service as U.S. intelligence officers in the Second World War will be told in Robert Kim’s book Crusade in Asia, to be published by the University of Nebraska Press in spring 2017.