It began in India. The wave of nationalism that has swept recent elections throughout the world first manifested in India’s 2014 general election. The canary’s song was silenced as it choked in the coal mine of national discontent. But at that critical moment we were too focused upon the peculiarities of India and pontificating on the historical-social context of the subcontinent. We did not pause to look at the dying canary’s cage. In isolating nationalism to India, we were blinded to broad changes in the global electoral environment. What happened in India would quickly spread both East and West and shake the very core of democracies.

The rise of nationalism in India propelled Narendra Modi to lead the Indian People’s Party (BJP) to a landslide victory in the 2014 general election. The BJP, a Hindu nationalist party with rare electoral success, became the first Indian party to win a majority of seats in the Indian parliament since 1984, a feat scholars thought impossible in India’s diverse electoral landscape.

Not only did the BJP defeat the Indian National Congress, the party of Mahatma Gandhi that governed with little competition since India’s 1947 founding, but also spurred the greatest voter turnout in India’s history. With over 66% of the 814.5 million eligible voters casting ballots, the BJP won the largest election in world history.

Similar to other movements, Hindu nationalism promotes territorial loyalty and patriotism. Even in a country with stark religious divides, the BJP advocates for unity through fidelity to the nation. Despite appealing predominantly to Hindus, the party prioritizes national allegiance above even that of religion. AB Vajpayee, a former BJP prime minister, wrote that “Mecca can continue to be holy for the Muslims but India should be holier than the holy for them.” Regarding religion, Vajpayee contends “we will live and die only for this country.”

The BJP’s electoral landslide came on the promise of a rising India. Similar to calls heard throughout elections in the past two years, the BJP played directly on anxiety and an unknown national future. Just as Donald Trump vowed to “make America great again”, the BJP promised “good times ahead” for India. When selected as the party’s leader, Modi touted the Hindu Right as the solution to national problems including communal violence, underdevelopment, and foreign insecurity.

Nationalism Rears Its Head in 2015

While observers marveled at Modi’s unlikely victory, nationalism was taking root in other democracies. The recent rise of the right has unseated governments in some contexts while merely causing disruptions in others. In the United Kingdom’s 2015 general election, for example, the Labour Party imploded as its supporters turned in droves to alternative parties. The Scottish National Party swept constituencies in the north while a vacuum of coordination amongst the opposition led the Conservative Party to easily win a majority of English and Welsh districts. Despite winning just one district, the nationalist UK Independence Party won an unprecedented 12.7% of the national votes.

European elections throughout 2015 continued to see voters abandon the left in favor of nationalist agendas. In Poland the far-right party, Law and Justice, won the election and has dramatically shifted the trend of European integration. Indeed, mistrust of the European Union and a policy of protectionism has plagued Poland’s foreign policy. While Denmark maintained a centrist government, the Danish People’s Party, a far-right populist party, nearly doubled its seats in parliament.

Turkey saw turbulent parliamentary elections with its first hung parliament in nearly two decades when the Justice and Development Party lost its majority. Disaffected Turkish voters propelled the Nationalist Movement Party with its espoused platform of Turkish nationalism and Euroscepticism to its best performance in years. And the Peoples’ Democratic Party, a pro-Kurdish party, cleared the minimum 10% vote threshold with a staggering 13% of the vote.

Even before these national elections rattled Europe, continental-wide voting for the European Parliament offered a foreshadowing. In a “political earthquake” Eurosceptic parties won over 19% of the seats in the European Union’s parliament. Many of these parties are committed to EU disintegration and have had their best electoral performance since the formation of the European Union.

Nationalism on the Rise in 2016

Public attention could no longer ignore the trend of growing nationalism as voters defied experts and polls alike. In one of the most politicized referenda in history, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Voters reacted in similar fashion to the general election of the previous year as distrust and frustration led voters to “take back control” in reasserting British sovereignty.

The world held its breath when Austrian voters failed to elect candidates from either of the two main parties in the first round of the presidential election. With one Green Party candidate and the other from a far-right populist party, any second round outcome would produce a non-centrist president. It took the annulment of second round ballot in May and a candidate rebranding himself from the Green Party to run as an independent for Austrian voters to reject a right-wing populist–some have suggested“neo-fascist”–candidate as their president.

Elsewhere in Europe, Slovak voters overturned the status quo in their national legislature. Electing the far-right People’s Party – Our Slovakia into parliament for the first time, voters turned against more centrist parties such as the Christian Democratic Movement which failed to win a parliamentary seat for the first time since 1990.

Even as far away as the Pacific, voters upended conventional politics in place of rightist rule. Populist politics is no new phenomenon in Philippine elections, but Rodrigo Duterte was unprecedented in his candor. When campaigning, he promised to “fatten the fish” in Manila Bay with the corpses of criminals and drug addicts. He even boasted of his involvement in vigilante justice through personally killing drug suspects. On the topic of territorial disputes with China, Duterte promised to “ride a jet ski while bringing the Philippine flag” and say to the Chinese: “This is ours. Do what you want with me.”

And most notable is the recent Donald Trump victory in the United States. In the course of his once-doubtful campaign, he rallied a base of voters to react against globalization, social progressivism, and America’s historic role as guarantor of the world liberal order. In regards to America’s place in the international system, for example, a typical Trump gambit was to qualify alliance responsibilities by pledging American commitment only to those NATO countries that pay their “fair share”, or to suggest that some countries must discontinue taking advantage of the American nuclear umbrella by getting their own. Further pledges of retraction from internationalism included Trump vehemently attacking existing trade agreements, such as by calling NAFTA “the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere”.

Nationalism does not look to be receding following the raucous elections of the past two years. Indeed, the recent events in England and the United States look to be a shot-in-the-arm to the movement. Like-minded nationalist leaders of the far-right, such as France’s Marine Le Pen and the Netherland’s Geert Wilders, have championed Brexit and Donald Trump’s election. Popular discontent continues to fuel nationalist advances.

Nationalism and an Uncertain Future

After losing bout after bout, the established political elites look to rebound in 2017. Rebranding nationalist messages, typically mainstream politicians seek to salvage international liberalism and an integrated international system. Led by Jeremy Corbyn, British liberals are usurping “take back control” in order to reclaim Brexit negotiations in favor of a more moderate divorce with the European Union. Elsewhere mainstream parties are crafting new survival strategies through co-opting challenges, and popular solutions real and perceived, from far-right nationalists. Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, for example, will likely adopt several rightist policies such as banning the niqab, a full-face Muslim veil, and adopting more-strict immigration laws. Whether such shifts in tactics ought to be seen as cynical pandering to popular sentiment or as simply admitting mistakes depends on one’s point of view.

Regardless, the success of these strategies in preempting rightist parties from siphoning votes away from the mainstream depends upon the dynamics of electorate dissatisfaction. Are we at the apex of the discontented voter or will the trend deepen? It may have begun in India, but as elections unfold across the world’s democracies we await to see the fate of nationalism and the right in 2017.

—

Timothy W. Taylor is Assistant Professor of Politics and International Relations at Wheaton College.

—

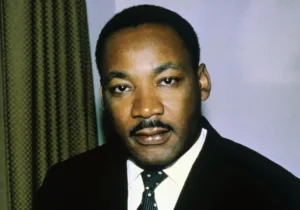

Image: Narendra Modi- With the Bright Young Minds of the Future. source: PM Modi’s flikr stream via wikimedia commons