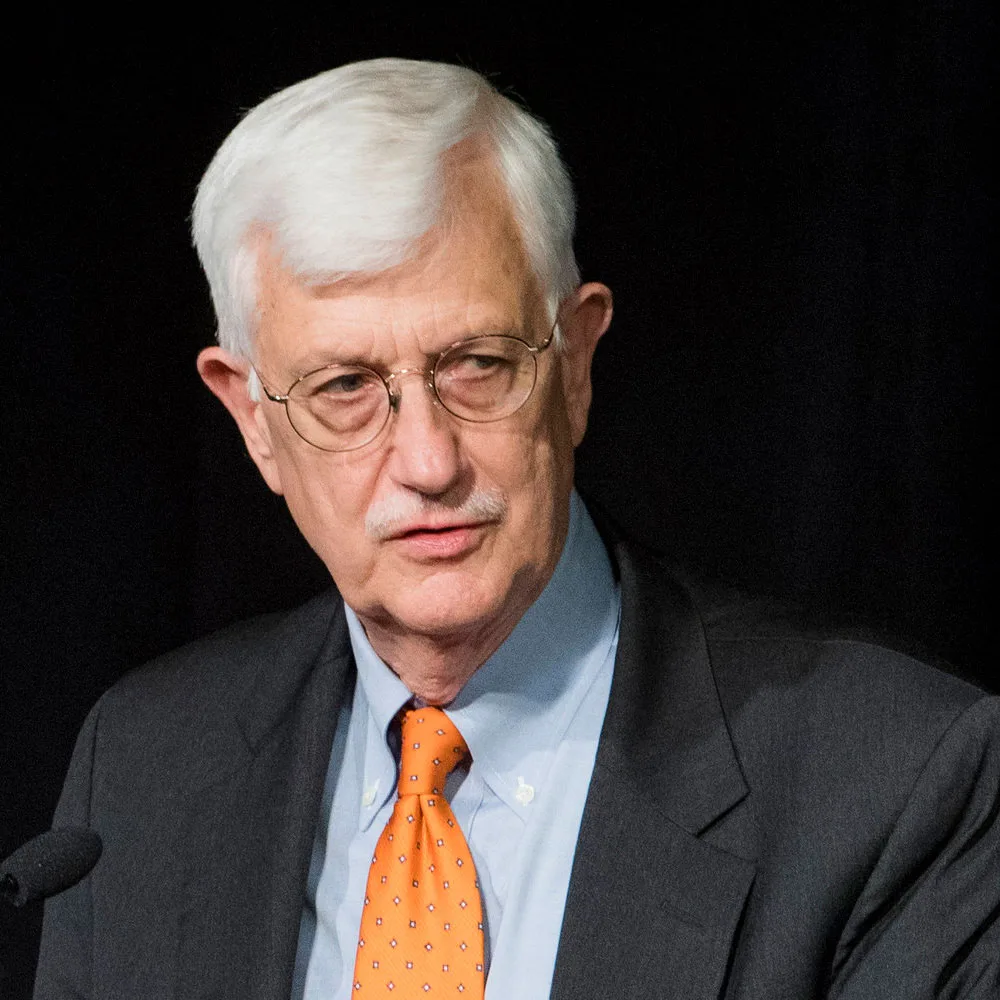

At Providence’s Christianity and National Security Conference in November 2019 at the Army Navy Club in Washington, DC, Thomas Farr explained why the most profound reasons for religious liberty are Christian.

Christian Reasons for Religious Liberty

Providence is the only publication devoted to Christian Realism in American foreign policy and is entirely funded by donor contributions. There are no advertisements, sponsorships, or paid posts to support the work of Providence, just readers who generously partner with Providence to keep our magazine running. If you would care to make a donation it would be highly appreciated to help Providence in advancing the Christian realist perspective in 2024. Thank you!

Events & Weekly Newsletter Sign-up

Receive the weekly email for all the latest content.