The division of Korea and the eradication of Christianity in the north after the Second World War, described in Part III, occurred despite the efforts of U.S. officials from the American Christian community in Korea who were concerned about the fate of their second homeland while serving in the U.S. government during the war. Belying the general view that the U.S. government was uninformed about Korea in 1945, they served in significant roles in multiple agencies of the wartime U.S. government and sought to direct U.S. attention and efforts toward Korea. Their lack of success and their complete absence from the historical record are cautionary tales relevant to current U.S. officials attempting to reconcile religious or other moral concerns with foreign affairs issues of today.

The American Christian missionary community in Korea, described in Part I, produced a second generation born and raised in Korea in which many were of military age during the Second World War. Like other Americans, they served in large numbers during the war, some in the armed services, some as civilians using the uncommon knowledge and experience that they had gained during their early years in Asia. A few of them rose to positions in U.S. government agencies in which they had opportunities to influence major U.S. decisions on actions in Korea during and after the war.

Dr. George McAfee McCune became the main expert on Korea for both the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the newly created intelligence service of the Second World War that was the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Department of State. A son of Reverend George S. McCune, an American missionary in Korea from 1905 to 1936 who headed Union Christian College in Pyongyang (see Part I), he had been born and raised in Pyongyang, and he earned the first doctorate in the study of Korea from a U.S. university in 1941. In February 1942, the OSS recruited him from his professorship at UC Berkeley to serve as its intelligence analyst on Korea. In 1943, he became the Korea desk officer for the Department of State, making him the leading official in the U.S. government for issues relating to Korea.

McCune strived to guide U.S. actions affecting the little-known country that he considered his personal responsibility, only to find that no one else cared about it. He argued for preserving Korea’s unity, mustering political, historical, and economic reasons, and he worked himself almost to death attempting to bring them to President Roosevelt’s attention prior to the Yalta Conference in February 1945. (He would die at the age of 40 in 1948 of heart problems that had afflicted him since childhood, which the stresses of his wartime work had exacerbated.) Roosevelt likely never saw the detailed report that he had prepared, which was one of many from the Department of State on the countries and issues to be discussed at Yalta. It had no apparent influence on Roosevelt’s discussions with Stalin, in which they agreed on a joint U.S./Soviet trusteeship over Korea that was a step toward its eventual division. Like many U.S. officials since him, Dr. McCune learned the hard way that interest in any one small nation overseas is rare in U.S. foreign affairs, which constantly faces numerous competing interests worldwide.

The OSS became the wartime home for numerous Americans from Korea, and some of them rose to positions in which they could have had significant effects on postwar Korea. Major General William Donovan, the director of the OSS, was unique among U.S. senior leaders of the Second World War in having significant interest in Korea, which he viewed as a key weakness within the Japanese Empire. Since February 1942, he had sought to create an alliance with the Korean Provisional Government in exile in China (described in Part II) and recruited Americans from Korea into the OSS, starting with Dr. George McCune. The OSS next found Clarence Weems Jr., who had grown up in Kaesong as a son of the Reverend Clarence Weems, the head of the Methodist missions in Kaesong and Wonsan from 1909 to 1940. Weems had joined Army intelligence as a civilian in February 1942, then as a commissioned officer in July 1942. In March 1943 he joined the OSS to become its lead intelligence officer for Korean affairs deployed overseas in Asia. In late 1944 to early 1945, Weems worked out terms for OSS operations with the Korean Provisional Government and its armed forces, which Donovan had sought for over two years. Called Project Eagle, the operations would send OSS-trained Korean agents into Korea and Japan for intelligence and sabotage operations, culminating in a guerilla war against Japanese forces.

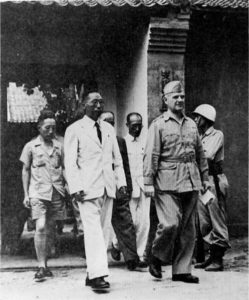

Project Eagle ultimately involved a staff of 30 Americans from the OSS, including 12 Korean-American officers and enlisted men. Its OSS commander was Captain Clyde Sargent, a China scholar who had been in China since the 1930s, recruited into the OSS in 1942. He became the lead operations officer working with Koreans and would stay involved with Korea for the rest of the 1940s. His deputy as Project Eagle’s intelligence officer was Captain Ryong Chyun Hahm. Hahm had resisted Japanese rule in Korea as a defense attorney in Seoul and then as a Methodist clergyman in Kaesong, then in the early 1930s emigrated to the United States, where he organized groups supporting Korean resistance against Japan. The OSS expedited granting him American citizenship and had him commissioned as an Army officer in order to send him to China as one of the leaders of Project Eagle. Sargent and Hahm worked with Korean military leaders who had been resisting Japan from exile in China since the 1910s and were eager to start the liberation of Korea as American forces crossed the Pacific toward Japan.

When the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki rapidly ended the war against Japan in August 1945, Project Eagle was practically the sole repository of American knowledge of Korea and connections to Korean political leaders that the U.S. government possessed. In Washington, OSS Director Donovan attempted to persuade President Truman to use it in Korea, seeing Korea with its position between the Soviet Union, Japan, and China as pivotal to postwar security in northeast Asia, and Project Eagle as a crucial asset for establishing a pro-U.S. democratic government and countering Soviet influence. In China, Sargent sought to bring Project Eagle to Korea to advise and assist the liberation of the country by U.S. forces, and Weems and the Korean Provisional Government discussed ambitious plans to expand the Korean force in China using Korean draftees in the surrendering of Japanese forces and send it to Korea as the nucleus of a Korean army and government.

All of their efforts failed because of policy disagreements and personal animosities among senior U.S. leaders. General Douglas MacArthur, designated to command the occupation of Japan and Korea, disliked Donovan and the OSS and had kept them out of his area of responsibility throughout the war, and he rejected using Project Eagle in postwar Korea as well. President Truman, also hostile toward Donovan and the OSS, ignored Donovan’s recommendations regarding Korea and a few weeks later ordered the disbanding of the OSS. As a result of these disputes at the highest levels of U.S. leadership, Weems, Sargent, and Hahm found themselves kept out of Korea, distant spectators as U.S. forces arrived in September 1945 completely unprepared, without clear orders from Washington, and lacking even basic knowledge of the country. Each eventually left the OSS and joined the U.S. military government in Korea as a political advisor, but only months later, after the opportunity to shape U.S. actions had passed. The political relationships and U.S.-trained forces that they had built in Project Eagle were lost to the U.S. military government in Korea, which would struggle with the same Korean political leaders for three years until the foundation of the Republic of Korea in August 1948.

The experiences of George McCune, Clarence Weems, and other American Christians from North Korea who attempted to guide U.S. actions toward Korea during the Second World War ended in disappointments, and they have been almost completely left out of the historical record in both the United States and Korea. They were ahead of their time when they sought to steer U.S. attention and efforts toward a country that few Americans knew and almost no U.S. officials considered to be significant. They did not succeed despite reaching positions of significant responsibility and, in the case of those who were officers in the OSS, receiving high-level support from one of the key leaders of the U.S. war effort. Their lack of success is unsurprising in retrospect, but their efforts were no more quixotic than those of many present-day officials and activists who are attempting to reconcile religious and other moral concerns with U.S. national interests and political dynamics in conflicts of today. They should be remembered as a significant part of the history of U.S. relations with Korea and as a lesson for those currently involved in foreign affairs.

—

Robert S. Kim is a lawyer who served as Deputy Treasury Attaché in Iraq in 2009-10.

—

Other Parts in the Series:

Part I: Jerusalem of the East: The American Christians of Pyongyang, 1895-1942

Part II: Christianity and the Korean Independence Movement, 1895-1945

Part III: Jerusalem Lost: The Eradication of Christianity in Pyongyang, 1945-1953

The story of the American Christians of North Korea and their service as U.S. intelligence officers in the Second World War will be told in Robert Kim’s book Project Eagle: The American Christians of North Korea in the Second World War, to be published by the University of Nebraska Press in spring 2017.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!