We enter the land officially delimited as an Indigenous Reservation belonging to the Surui-Paiter tribe in southern Amazon region. The equatorial sun burns the landscape, turning the color of the naked hills into a brownish yellow. Lonely Brazil-nut trees randomly standing on the horizon remind us the pastures the Suruí now use were once a part of the majestic Amazon forest. The view does not change from what we saw outside the reservation, the pastures and cultivated lands of the Brazilian settlers. All around, the pastures and starving coffee plants continue along the dirt road that takes us to one of the villages. At a distance a group of trees show that the jungle still exists and awaits a few kilometers down the road. Both jungle and pastures are now part of the reservation and define the lifestyle of the Suruí-Paiter. When the lands were demarcated as reservations and returned to the Suruí, the original owners, a part of it was already deforested and developed into small productive farms. That is where the Suruí established their villages and gladly continued their agricultural mission, not strange to their traditional lifestyle. The subsistence agriculture replaced the hunter-gatherers’ precarious life of the past.

Not anymore. Now they are forbidden by contract to farm and raise cattle in the previously deforested lands and even to hunt or gather anything from the vast extensions of remaining jungles. The Suruí cannot cut trees for building homes or canoes. They cannot use the forest or the lands supposedly dedicated to their usufruct. The lands are now under contract with a gigantic international corporation for the capture of carbon gas.

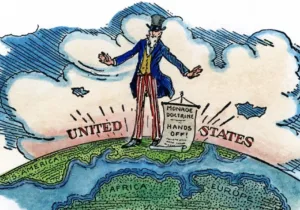

For big industries of the West and environmental NGOs, purchasing UN-sanctioned Carbon Emission Credits in indigenous reservations, vast stretches of jungle apparently untouched and already protected under national laws, seemed to be a good idea. However, the morality of the whole thing is gray, to say the least. REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries) is a product of UN discussions that happened in Bali, Indonesia, the COP 13 (Conference of Parties 13) that involved the 192 countries that signed the Kyoto Protocol. Trees of the world’s big forests demand a great quantity of carbon to grow and maintain themselves, a process that diminishes the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Forests help mitigate the greenhouse effect caused by pollution emitted by industrialized places. Purchase of carbon credits through REDD+ projects provides a moral alibi for Western industries to continue polluting the environment. They do not have to adjust their emission levels. It also gives these companies power to hijack native peoples’ rights to use the environment. Business buyers of REDD+ carbon credits are by all appearances admirable. They partner with indigenous tribes for the noble goal of protecting the environment. In reality, they are forbidding the under-developed economies from interacting with the environment even in the subsistence form that for the most part, is sustainable. Those businesses therefore assure that the tribes remain in poverty, dependent on foreign or government money for basic survival.

Indigenous ways to live with the forest do not always equate with the expectation of environmentalists who worked to create legal rules of what is considered “preserving” the jungle. Tribes living off their surroundings need to tame it, as much as any other human group. They need to cut trees to make trails, build homes and canoes, or sometimes only eat fruit. They need to burn parts of the jungle to plant basic starches for their diet. They need to fish, hunt, collect, and gather resources the jungle provides. That is their “ancestral” way to deal with the jungle. Most of these activities include “devastation, cutting, burning and destruction” of the environment according to the language of carbon credits regulation.

The destination of money acquired by the indigenous people when selling carbon credits is another serious problem. Who should get the money? As much as we would like to think indigenous tribes mirror a perfect socialist society where any money given to the top leaders will be equally distributed to all other members, the reality is not so simple. Many tribes are organized into clans and do not have one common leader for all the people. Usually, money is given to whomever is the most savvy leader in outside matters, the best communicator in the national language, and the best networker with FUNAI (The Bureau of Indigenous Affairs) or the NGOs that work as intermediaries between big business and tribes. Moreover, because human beings are sinful as Christian doctrine explains and as even a casual glance at ourselves and our neighbors should demonstrate, many leaders are selfish, corrupt, and capable to use collective money for personal pleasures, and do not feel particularly responsible for carrying the burden of their tribe. Corruption is not a feature unique to the West.

Now environmental NGOs and NGOs whose goal is to protect the lifestyle of the indigenous populations are on opposite sides. In 2014 the magazine Porantim,[1] the voice of a Catholic missionary branch, published an entire issue about the harmful human consequences of REDD+ projects in places like Kenya and Indonesia. In Brazil, the Munduruku, the Karipuna, the Suruí of Pará, and the Parintintin of Amazonas are some of the many tribes that have been deceived by these few-million-dollars contracts besides the Suruí-Paiter.

The Surui-Paiter are a Tupi-Monde tribe that was completely isolated until 1969 when a rapid and devastating change took place around them. The military dictatorship of Brazil, under a banner of territorial integration and development, subsidized massive migration of small farmers from the south to the far north. Many families that lived off leased lands in southern Brazil saw in this new push the only way to have finally a farm to call their own. Roads were cut into raw jungles, and land was divided into smaller plots. In the middle of all this, many tribes were caught between their traditional lifestyle and the gigantic machines of progress. That was how the Suruí-Paiter became dependent on four-wheel-drive Toyotas and cell phones in less than five decades of contact.

Unfortunately for the tribe, the 248 thousand hectares of reservation, the size of Italy, are rich and fertile with great bio-diversity and precious minerals. In the last 50 years, they have had to deal with the greed of woodcutters, miners, and now environmentalists, all wanting a cut of the subsoil, the land, and the air they breathe. This is not to say that the Surui are innocent victims of an international scheme. One of the clan chiefs, mentored by a national environmental NGO with a fat international contract, rapidly learned how to take advantage of the system. The project became a scheme for the enrichment of a few lucky people and the impoverishment of the whole group. The clans that did not receive any benefit are desperately trying to nullify the contract so they can keep cultivating the land and share the little that is left of their traditional lifestyle with their future generations.

As environmentalists promote these REDD+ carbon credits, moral uncertainty increases. Are they a “good thing”? Decades from now, are we going to be grateful for these courageous initiatives to save the world, or lament once again the consequences that Western quixotism had on the lives of the most vulnerable peoples on earth?

—

Braulia Ribeiro is an ex-socialist Brazilian now living in New Haven, CT. She is an MA student at Yale University as well as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Aberdeen. Prior to her life in the US, she was a volunteer social worker and missionary in the Amazon Region, where she and her husband founded a missionary non-profit, serving over 30 Amazonian tribes. She was the president of one of the largest missionary organizations in Brazil (JOCUM- Jovens Com Uma Missão) for 4 years. In the US she began to question her Marxist background and through further study embraced a different worldview. She has a BA in Ethnolinguistics from the University of the Nations and an MA degree in Descriptive Linguistics from the Universidade Federal de Rondônia.

Feature Photo Credit: Aerial view of the Amazon river and rainforest, near Manaus, the capital of the Brazilian state of Amazonas. Brazil. Photo by Neil Palmer/CIAT for Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), via Flickr.

Click here to read an open letter in Portuguese from the indigenous peoples’ lawyers describing their case against the REDD+ program and other issues. The letter was provided by Braulia Ribeiro.

[1] Porantim, Ano XXXVI, n. 368, Setembro, 2014.