“We’re turning the page on a decade of war,” President Barack Obama promised Americans in 2012. He was definitely in tune with the American people—wearied, as they were, by the costs of open-ended military interventions from Afghanistan to Africa—but he was way off on the war’s length.

In fact, by the time President Obama reassured the American people they could turn the page on a decade of war and “focus on nation-building here at home,” a Saudi terrorist had been waging global guerilla war against America for the better part of two decades. The attacks of September 11, 2001, merely marked the moment America awoke to the nightmare.

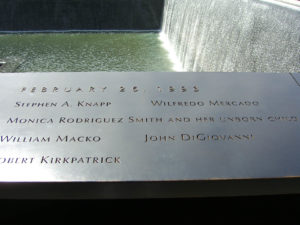

Few Americans remembered on 9/11 that Osama bin Laden’s henchmen had attacked the World Trade Center years earlier, on February 26, 1993, when Ramzi Yousef detonated a van full of explosives in the underground parking garage of the north tower. The blast blew a hole 100-feet wide and five stories deep into the bowels of the tower, killing seven and wounding 1,500.

We later learned that one of Yousef’s co-conspirators was related to bin Laden; that Yousef had stayed in bin Laden’s guest house before and after the attacks, as NBC reported; and that Yousef was the nephew of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed—the man who described himself as al-Qaeda’s “military operational commander for all foreign operations around the world” and took credit for that first attack on the World Trade Center.

In the months and years that followed, the attacks increased in frequency, ferocity, and audacity.

In October 1993, Somali warlord Farah Aidid’s militia brought down two American helicopters and cut down 18 American troops in a daylong gun battle in Mogadishu. “My colleagues fought with Farah Adid’s forces in Somalia,” bin Laden later smilingly revealed.

In November 1995, four “self-described disciples of bin Laden” used a truck bomb to kill five American servicemen in Riyadh.

In August 1998, al-Qaeda conducted simultaneous attacks on United States embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 240 people, including 12 Americans.

In October 2000, al-Qaeda suicide-bombers attacked the USS Cole in the Yemeni port of Aden, killing 17 Americans.

Then, in September 2001, al-Qaeda maimed Manhattan and scarred the Pentagon, murdering 2,977 people.

Targets

Bin Laden had warned us that his cult of killers “do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians; they are all targets.” That became obvious on February 26, 1993, and again on September 11, 2001, and again and again in the years that followed.

After 9/11, the jihadist war on civilization bloodied Morocco and Mumbai, Manchester and Madrid, Pakistan and Paris, Saudi Arabia and San Bernardino, Istanbul and Indonesia, Ottawa and Orlando, Britain and Brussels, Boston and Baghdad, Ft. Hood and the Philippines, Nairobi and Nigeria, Ankara and Amman. The list goes on and on.

Some of the attacks were carried out by al-Qaeda, some by its offshoots, and some by organizations that used it as feedstock for their rise. But all of them were inspired by al-Qaeda and its founding father. It’s as if bin Laden broke some sort of invisible barrier with his audacious attacks on America.

Devoid of compunction, constraint, or conscience, bin Laden’s death cult attacked commuters in London, vacationers in Bali, businessmen and children in Manhattan and Arlington and Shanksville, Christian churches in Pakistan and Baghdad, and Shiite pilgrims in Karbala. In 2007, long before the Islamic State (ISIS) brutalized Iraq’s Yazidi minority, al-Qaeda murdered 400 Yazidis, just because they were Yazidi.

In 2012, the remnants of al-Qaeda in Iraq—which had been crushed by the US surge only to reconstitute and rebrand after the US withdrawal—“morphed into the earliest version of ISIS,” as the Financial Times reported. ISIS has been called “worse than al-Qaeda,” and perhaps deservedly so. As proof of its savage piety, ISIS summarily executed thousands of Shiite Muslims; drowned and burned alive prisoners of war; conducted genocide against Yazidis and Christians; executed imams and hospital workers; ordered Christians to convert or die; conducted a systematic campaign of rape in conquered territories; sold children into slavery; and used “mentally challenged” children as suicide bombers.

Differences

This is the enemy the US military has been fighting for decades now. However, the US is not at war with Islam—after all, in the past quarter-century US troops have rescued Muslims in Kosovo, Kurdistan, Kabul, Somalia, and Sumatra—but it is at war those who would force people to submit to Islam. It is at war with those who take literally Muhammad’s injunction “to fight all men until they say, ‘There is no god but Allah.’” It is at war with those who “do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians.” It is at war with murderers and rapists masquerading as holy men. It is at war with those who seek to destroy civilization.

Make no mistake: There’s a vast difference between those who use force to defend civilization and those who use force to dismember it. Motives matter; as scripture reminds us, motives are weighed by the Lord. At its core, the primary motive of our jihadist enemies is to kill and injure innocent civilians. Yes, the bin Ladens, Baghdadis, and Zawahiris of the world have a broader political goal, but to achieve that goal they must achieve the primary goal of killing and maiming innocents. Terrorism loses its power without achieving that goal.

America is not perfect. Without doubt, innocent people sometimes die as a consequence of American military action. But the undeniable difference between the terrorist and the US soldier, sailor, airman, and Marine is motive and intention. Americans do differentiate between combatants and civilians, and we go to great lengths to prevent the loss of civilian life.

We see the difference in the way the enemy defines success and the way we react to failure. When our terrorist enemies kill civilians, they cheer and use their latest atrocity as a recruitment tool. When our defenders kill civilians, they order bombing pauses; they investigate and apologize; they demote and court-martial; they change targets and scrub missions. And their civilian leaders invest in ever-more precise, ever-more expensive weapons systems to prevent mistakes.

Attention

As ISIS collapses in Iraq and Syria, as al-Qaeda’s attacks on the homeland fade into history, Americans may be tempted to declare victory and turn their short attention spans elsewhere. That would be a mistake.

In December 2017, the US military killed “multiple” al-Qaeda operatives in Afghanistan in a series of operations spanning several weeks. Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats reported this month that al-Qaeda is operating across large swaths of Mali, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Niger, Kenya, Somalia, Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

This helps explain why US troops are still in Afghanistan, why the US military is bolstering its presence in Syria, and why US weapons releases are up 44 percent in Afghanistan, 29 percent in Iraq/Syria, and almost 10 percent in Yemen.

The war bin Laden began 25 years ago—what US military leaders aptly call “the long war”—is far from over.

—

Alan Dowd is a contributing editor to Providence and a senior fellow with the Sagamore Institute Center for America’s Purpose.

Photo Credit: World Trade Center, circa 1980 – 2001, by Carol M. Highsmith. Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024