This article about the Christrian militias in northern Iraq first appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of Providence‘s print edition. To read the original in a PDF format, click here. To receive a complete copy of future issues as soon as they are published, subscribe for only $28 a year.

Religious and ethnic minorities live a precarious existence during civil wars. In a war between the incumbent state and an insurgent challenger, minority group leaders may pick one side over the other. However, if they choose the loser they will be open to charges of collaboration and become vulnerable targets of vengeance. On the other hand, if the minority chooses to stay out of the fight altogether, the failure to mobilize may itself leave them defenseless. Moreover, some civil wars and insurgencies are more complicated than others. Multiple actors fighting or competing for control of the state make things even more complicated, especially if minority groups themselves fragment into multiple factions.

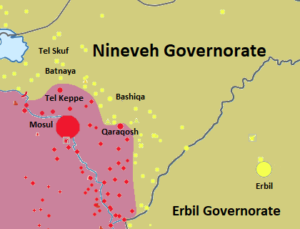

In our brief account here, we will describe the formation and fragmentation of self-defense forces (militias) within the Christian population of the Nineveh Plains. We will trace the development of their post-2003 self-defense force, the crisis of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’s (ISIS) attack, and the current fractured state of Christian forces in the area. The situation of the Nineveh Plains militias illustrates how evolving political relations can open a broad set of strategic choices. In turn, we will show how different actors will have incentives to choose differently across this set of options.

At the time of the American invasion in 2003, an estimated 1.5 million Christians lived in Iraq, including many Assyrians in northern Iraq around Mosul. By the time ISIS swept through northern Iraq in 2014, that figure may have fallen to roughly 400,000. If significant numbers do not return, the Iraq War and its aftermath could lead to a near elimination of a religious minority with roots going back nearly 2,000 years; some Christian groups carry deeper ethnic identities that are even older. It would not be the first time a sizable ethno-religious minority has disappeared from Iraq’s mosaic of peoples. In 1900, Jews comprised one-fourth of Baghdad’s population, totaling about 50,000 residents. Over the course of the next century, their numbers became miniscule.

During several visits to the region, we’ve tried to learn more about the Christians of Iraq, particularly in the area of the Nineveh Plains. In the fall of 2014, the senior author—Petersen—conducted a focus group session with 15-20 Christian refugees from Qaraqosh who found safety in Jordan after fleeing ISIS. In the summer of 2017 in Erbil, capital of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), Cancian interviewed several officers in the Nineveh Plains Guards (NPG), the largest Christian self-defense force.

Generally speaking, minority group political leaders have a range of choices in deciding whether and how to mobilize their populations in armed groups. First, they can simply try to stay neutral and not mobilize at all. Second, they can encourage their members to join one side’s armed forces as individuals in hopes of winning favor with that group. Third, they can mobilize militias and associate that force with one of the combatants. On top of these choices, minority leaders must also consider whether to mobilize as a unified entity or as a sub-group. Mobilizing as a sub-group may allow the group to pursue political goals or spoils, but it will also reduce the group’s leverage while increasing its vulnerability.

After 2003, the Christians in Mosul proper basically chose neutrality. Nevertheless, targeted killings and kidnappings drove them out of the city. Reacting in part to the fate that befell their brethren in Mosul, the Christians of the adjacent Nineveh Plains chose differently. In the summer of 2004, a Christian self-defense force was organized in Qaraqosh (also called al-Hamdaniya, Bakhdida, or Baghdeda), a Christian city that is the largest city in the Nineveh Plains. It lies 20 miles from Mosul, and critically in the “disputed territories” between Kurdish and Iraqi Government control.

According to officers in the self-defense force, the prime mover was a Catholic priest from the town, Father Louis Qassab. In response to ISIS violence in Mosul, he contacted Sarkis Aghajan, an Assyrian politician who was the Minister of Finance and the Economy in the KRG from 1999-2006. Sarkis Aghajan contacted a trusted lieutenant who had served in the Iraqi Army, Fuad Arab (a nom de guerre), to organize a force of Christians in Qaraqosh. Fuad Arab in turn enrolled a network of Christians of former members of the Iraqi Army and Intelligence Services to be the backbone of the group, and they in turn recruited younger Christians to be junior soldiers.

From an initial force of just 245, the group expanded to over 1,000 members who patrolled and manned checkpoints inside the city. While at first they were unarmed, the KRG eventually provided them Kalashnikov rifles. The decision to align with the Kurds, rather than the Government of Iraq (GOI), was likely influenced by the strong ties that Sarkis Aghajan has with the Barzani family. There are reports that he grew up in Iran with Nechirvan Barzani, the Prime Minister and nephew of President Massoud Barzani, and that Aghajan was even in the Kurdish peshmerga (military forces). On the other hand, American documents published in WikiLeaks indicate that in private he complained about Kurdish incursions on what he believed were historically Christian lands. Still, from an early stage the force, dubbed the Nineveh Plains Guards, received material aid from the KRG and kept the area safe from the bloodshed that plagued Mosul until the invasion of ISIS in August 2014.

In sum, while violence raged in nearby Mosul, Christian leaders in Qaraqosh made a decision to organize their own militia, people it with Christian veterans of the Iraqi Army, and tie it to the most powerful political actor in the region, the KRG and its peshmerga. Other leaders in smaller and less vulnerable localities chose not to mobilize an armed force; this choice was safe given the perceived power of the peshmerga and the NPG. There was only one significant Christian militia, so there was no fragmentation.

After taking Mosul in June 2014, ISIS paused briefly before turning its sights eastward in August. Losses from ISIS’ advance did not include just Christian lives and property. First, Christian confidence in Kurdish protection declined when the peshmerga was unable to defend the Nineveh Plains. Second, and perhaps as a result of the first, Christians in the region fractured into several militias. While there had always been different political parties, before 2014 these differences did not result in the creation of competing armed groups. The Kurds’ previous hegemony in the area prevented splintering because the peshmerga in the area was the clear partner for assistance. After 2014, the Kurds’ reliability was questioned when ISIS overran every major Christian town except al-Qosh in the north. Additionally, it wasn’t clear whether Erbil or Baghdad would eventually liberate the Nineveh Plains from ISIS control (assuming ISIS would be defeated).

In effect, two polities were now competing to be the legitimate government in the Nineveh Plains: the KRG and the GOI. Neither was strong enough nor had the will to displace the other. Both could produce mobile and local security forces. For Christian organizations, the choice set broadened to include the following realistic options:

1) Do not mobilize at all; stay neutral

2) Mobilize and integrate with the existing Christian militia (NPG)

3) Mobilize an independent group and ally closely with the KRG

4) Mobilize an independent group and ally closely with the GOI

5) Mobilize an independent group and occupy a position between the KRG and GOI

As it happened, organizations covered the range of options. Some Christians stayed in the NPG, which was closest to the Kurds. Some split from the NPG and formed their own groups but still maintained ties with the Kurds: these groups include Dwekh Nawsha, the Nineveh Plains Protection Units (NPU), and the Nineveh Plains Forces (NPF). As it became clear that Baghdad would liberate most of the Nineveh Plains, the NPU and NDF strengthened their relationships with the GOI, who is now their main partner. Finally, one force, the Babylon Brigade, completely broke with the Kurds and threw themselves in with central government as members of the Popular Mobilization Units.

Remaining closest to the KRG are members of the NPG, now officially members of the Zeravani forces under the KRG’s Ministry of the Interior. As such, they received salaries and training from the KRG. In the summer of 2016, the junior author visited them as they trained in Bnaslawa with members of the Western Coalition. Five hundred of them were receiving a two-week refresher course, and morale seemed high. Abu Hakem (a nom de guerre), their commander, claimed that they had 2,600 members but planned to expand to 3,500. While they had hoped to return to Bartella and Qaraqosh during the upcoming Mosul operation, these areas wound up being liberated from ISIS by the central government. In the summer of 2017 during a return visit, the junior author witnessed that the NPG continued to guard refugee camps for Christians in the KRG and hoped that a change in political fortunes would allow them to return to their homes. While they were once the only Christian militia, others have arisen.

Dwekh Nawsha (meaning “self-sacrifice” in Syriac, a derivative of Old Aramaic, the language of the Assyrians) formed in the Tel Skuf area as the armed force of the Assyrian Patriotic Party (APP). While separate from the NPG, it still coordinates its operations with the Kurds, who supply the group with arms and equipment. The APP has had a tumultuous relationship with the KRG. Initially founded in Baghdad during the 1970s, it had to move its operations to the KRG for security reasons during Saddam Hussein’s rule. Despite periodic disputes with the KRG, it has mostly been safe and welcomed. Its base of support’s location in Tel Skuf, which is close to Kurdish strongholds, also helps to explain Dwekh Nawsha’s allegiance. The Kurds were more likely to eventually liberate the area, which happened.

As the peshmerga rolled back ISIS, Dwekh Nawsha has been able to move southward and provide rear area security. After the Tel Skuf operation, the Assyrians were put in charge of security in the town of Baqofa. It wasn’t without risk: in March 2016, a US Navy SEAL was killed while helping peshmerga and Dwekh Nawsha forces defend themselves from an ISIS attack. When Batnaya was liberated during the Mosul Operation, Dwekh Nawsha was able to move there and provide security, although fighting had mostly destroyed the town. On a visit to the border between Iraq and the KRG at Batnaya, the junior author noted no Dwekh Nawsha soldiers present. The town was still largely in ruins with very few residents. The Assyrians continue to occupy some rear areas of that sector but have no frontline responsibility.

Indicating greater disillusionment with the Kurds than in the case of Dwekh Nawsha, two other groups not only split with the KRG-sanctioned NPG but aligned themselves increasingly with Baghdad as the campaign against ISIS progressed. The Nineveh Plains Protection Units (NPU) was formed by the Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM). The ADM has long balanced between Erbil and Baghdad, holding two seats in the Kurdistan Parliament and two seats in the Council of Representatives of Iraq. The ADM also maintains a strong political movement in the United States, particularly in Illinois. The ADM, however, does not wish to create a separate Assyrian region as some members of the diaspora want, according to its leader, Yonadam Kanna.

After 2014, the ADM formed the NPU in al-Qosh, which never fell to ISIS and was instead under peshmerga control. A lack of faith in the Kurds’ ability to defend them was an explicit motivating factor. “If someone from Zakho [a town in northwest Iraqi Kurdistan] protects the Nineveh Plains, he doesn’t care, because his family is somewhere else. Local people have family here, and they will not run,” said Youra Moosa, an NPU political coordinator, in an interview with Matt Cetti-Roberts. Initially the NPU established itself in the KRG but grew closer to Baghdad as it became clear that the GOI would liberate the Ninevah Plains and not the peshmerga. After the Iraqi Army liberated the towns of Bartella and Qaraqosh in the Mosul Operation, despite initial attempts by the KRG to block its movement, the NPU was able to move down and become the official security force for those areas along with another force, the Nineveh Plains Forces.

The NPF has a similar story to the NPU. It is affiliated with the Bet-Nahrain Democratic Party, which held a seat in the KRG’s parliament before the 2013 election, and now holds seats in Iraq’s regional governments for Baghdad and Nineveh. Similar to the NPU, it was based in the KRG’s area of control and initially supported by the peshmerga. During the Mosul Operation, it moved into Bartella, where it has coexisted with the NPU.

Finally, the greatest break with the KRG came from the Babylon Brigade, which joined the central government’s Popular Mobilization Units (PMU). Led by Rayan al-Kildani, it is unclear what political party, if any, it is affiliated with. Even a BBC correspondent who visited its Baghdad headquarters in 2016 was “not sure how seriously to take Kildani,” and implied it joined for the generous salaries.

This proliferation of armed forces has inevitably increased hitherto latent rivalries within the Christian community. Patriarch Louis Sako, the head of the Chaldean Catholic Church in Baghdad, has spoken out against the formation of any Christian militias. Despite an accord in October 2016 to unify all Christian forces, divisions have deepened. On July 15, 2017, clashes broke out between the NPU and the Babylon Brigade in Qaraqosh. After a brief skirmish, the Babylon Brigade members were expelled and, according to a TV station associated with the NPU’s political party, the Babylon Brigade was forbidden from returning to the town. Each of the Christian forces now occupies a separate area of the Nineveh Plains with no ability to move between them.

| Militia | Location of Origin | Alignment | Political Party Affiliation |

| Nineveh Plains Guards (NPG) | Qaraqosh | Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG): now officially members of the Zeravani forces | Chaldean Syriac Assyrian Popular Council

|

| Dwekh Nawsha | Tel Skuf | KRG | Assyrian Patriotic Party (APP) |

| Nineveh Plains Protection Units (NPU) | al-Qosh | Between KRG and Government of Iraq (GOI), leaning GOI | Assyrian Democratic Movement (ADM) |

| Nineveh Plains Forces (NPF) | Between KRG and GOI, leaning GOI | Bet-Nahrain Democratic Party | |

| Babylon Brigade | GOI: integrated into Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) | Unclear |

In summary, five significant local Christian militias emerged in the Nineveh Plains in the post-ISIS period. In their political alignment, these groups covered the range of options with one continuing its close relationship with the KRG, one deciding to align with the GOI and Popular Mobilization Units, and three others positioning themselves between the KRG and GOI.

First, after becoming direct victims of violence in 2014, no significant Christian groups chose neutrality. Unsurprisingly, the actual experience of violence spurs mobilization, even if the abstract threat of violence may not. Second, most Christians fought in Christian militias rather than integrating into larger forces. Their militias were locally based and focused on local defense. As in much of the rest of Iraq, militia formation was mobilized along group and territorial lines. Third, in the presence of two competing potential hegemons, minority group leaders envisioned strategies that might provide both resources and autonomy. Political agendas that had lain dormant can now find life. Much as states in the Cold War period developed strategies of non-alignment between the two superpowers, minority group factions in the Nineveh Plains could mobilize organizations and militias and position them between the GOI and the KRG. It remains to be seen whether the resulting fragmentation of the Christian minority will lead to less overall leverage and greater vulnerability in the medium and long-terms.

The Iraqi Christians’ fractured state presents a dilemma to United States policymakers. The largest armed group, the NPG, remains in exile in the Kurdistan Region. Christian opinion on the Kurds, however, seems to be divided. Many members of the Iraqi Christian diaspora despise the Kurds due to their complicity with massacres of Christians in the early half of the twentieth century. This historic animosity, however, contrasts with the fact that since 2003 Christians have been more secure in Kurdish areas than in the south. The diaspora’s preferred solution of founding a separate Nineveh Plains region, moreover, does not seem to have the support of many Iraqi Christians who still live in the country. Many Christians worry about encroachment by the Shabaks, a Shiite religious minority that has joined the Popular Mobilization Units. The fundamental problem of geography, that the Nineveh Plains lie on the border between Kurds and Arabs, will be the primary obstacle to a solution. The Kurds’ independence referendum has only complicated the situation. US policymakers who want to help the Christians will have to untangle a knot of complicated relationships and dynamics to restore Christian security. Time is not on their side. There is a very real risk that, without a satisfactory long-term solution, the Christians of Iraq will go the way of the Jews of Iraq: a once vibrant community consigned to the pages of history.

_

Roger Petersen holds BA, MA, and PhD degrees from the University of Chicago. He has taught at MITsince 2001 and is the Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science. He has written three books: Resistance and Rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe (2001), Understanding Ethnic Violence: Fear, Hatred, Resentment in Twentieth Century Eastern Europe (2002), and Western Intervention in the Balkans: The Strategic Use of Emotion in Conflict (2011), all with Cambridge University Press. He is currently working on a manuscript entitled “A Social Science Guide to the Iraq Conflict.”

Matthew Cancian is a PhD student at MIT in Security Studies and International Relations with research interests in military effectiveness and civil wars. After receiving a BA from UVA, Matthew served as an artillery officer in the United States Marine Corps. After leaving as a Captain, he received an MALD from the Fletcher School, where he received the Edmund A. Gullion award for academic achievement.

Photo Credit: A soldier from the Nineveh Plains Protection Unit takes cover and returns simulated fire during react to contact training on May 18, 2016. Staff Sgt. Sergio Rangel. Source: US Army.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024