Last week’s announcement that the Trump administration will be pulling troops out of Syria has prompted a flurry of hostile commentary against the president’s abandonment of allies, his kowtowing to Russian interests, and his misunderstanding of what “defeating ISIS” actually looks like. This is all commentary with which I agree.

But there is no doubt that President Trump believes his decision was made in the best interests of the American people – and he’s not alone. On December 20, he channeled Americans on both right and left when he tweeted, “Does the USA want to be the Policeman of the Middle East, getting NOTHING but spending precious lives and trillions of dollars protecting others who, in almost all cases, do not appreciate what we are doing? Do we want to be there forever? Time for others to finally fight…..” A motley crew of Democrats and Republicans rose in acclamation of his decision.

There’s a kernel of truth in what Trump says: Our current policy in the Middle East has indeed stagnated. But that just means a smarter policy – not retreat.

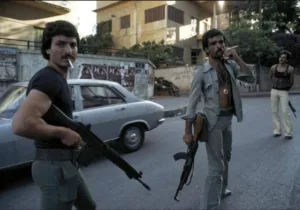

President Trump is making a major mistake. Redeploying American forces out of Syria could increase violence in the short term as Assad moves to reconquer the eastern portion of the country. It will expand Russian, Turkish, and Iranian influence in the proximity of our allies Israel and Jordan. Worst of all, it sends a clear message to the world that America feels no loyalty to its allies. The Kurdish, Syriac, and Arab soldiers who fought with us against ISIS – soldiers who have now been abandoned to the predations of local enemies – are just the most recent casualties of a US superpower that seems to have lost its identity on the world stage.

It isn’t just that we’ve forgotten our values; we’ve forgotten our interests, too. Trump shares the belief of many Americans that maintaining 2,000 US troops in eastern Syria is akin to being the “Policeman of the Middle East” and gives us nothing tangible in return. The problem is that Americans can’t see the world for what it is, and American policymakers aren’t explaining it to them. Very few, it seems, understand the concept of limited intervention.

***

REMEMBER AMERICA’S ATTACK on Syria a few months ago? No, you probably don’t. The news cycle is moving fast these days.

Let me refresh your memory. Back in April the United States, Britain, and France launched a combined missile strike against the Syrian government in response to a chemical attack that had killed 70 people. The strike gave rise to the usual excesses on social media, and if you didn’t know any better you might have thought we were either overthrowing Assad and installing a new democracy or standing by while he gassed his own people. It seemed like everything was at stake, or nothing, depending on who you asked.

The core of the debate was whether the US was right to launch a limited intervention against Assad’s chemical weapons program: a discreet volley of 107 missiles that degraded but did not destroy his regime. Limited interventions are low-cost, small-footprint military operations that take place when America gets involved somewhere in the world and does less than everything but more than nothing. Much of our current military activity falls in this category.

Lots of people had a problem with this apparent half-measure. Some wanted more. Others wanted much less. “Either win the war or stay out of it,” seemed to be a common sentiment.

The concept of limited intervention is hard for Americans to grasp because we have trouble talking about limited anything. If we’re going to fight, we want to win. And we don’t want a technical knockout. We want the other guy splayed out on the floor.

World War II spoiled us. Our big debut on the international stage brought us a definitive victory over an obvious evil, yet such epic confrontations are uncommon these days. We crave battles of Troy-like proportions, but the world keeps giving us suicide bombers in “man-jammies.”

The disparity between our overwhelming power and our failure to achieve definitive victory is a source of constant frustration for the American people. How can we be so strong yet so impotent in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria? One president after another has tried to explain what we’re doing in these far-flung locales, but they never seem to win in any of them. And if we can’t win, why are we still fighting? The American people want to know.

Someone needs to give an answer. In an era when definitive victories are less and less common, this answer is more important than ever. Indeed, the failure to craft meaningful domestic narratives is one of the biggest holes in US foreign policy strategy. Democratic countries need the support of their citizens to maintain a consistent posture abroad, and that support is most necessary when launching military interventions in foreign countries. Most Americans aren’t interested in big ideas from international relations theory or sermons about axes of good and evil. They want clear answers that make sense.

Limited intervention is helpful here. But, like anything else, it needs to be properly explained.

ANY FOREIGN POLICY explanation should begin by accurately describing what the world looks like in late 2018. Whether we know it or not, we live in the world America built. When we defeated fascism and communism in the twentieth century, we took our place at the head of the safest and most prosperous international order in history. This worldwide network of friendly countries backed by American economic and military power is, simply put, the American neighborhood.

Note that America controls a neighborhood, not an empire. Neighborhoods are shared communities where each family manages its own property. Empires differ in that one family claims ownership over the properties of everyone else. The American neighborhood has fences. The Roman Empire did not.

That doesn’t mean that everyone in our neighborhood is happy or agrees with us. We happen to think that liberal democracy offers the best model to organize human society, but others disagree. We hope they see the value of our approach and adopt it as their own, and we spend lots of time and money to persuade them, but we don’t rampage around the neighborhood forcing other people to think like us. We ask: “Are you neighborly? Can you live here peacefully alongside the rest of us?” Our belief is that working together will eventually influence unfree states to evolve in a positive direction.

If every country is sovereign over its own property, how is this neighborhood controlled by America? Two ways. The first is our massive financial and military power. In a community of regular-sized houses, America is a sprawling estate. And although it lies on the furthest edge of town, its sheer size makes it the neighborhood’s natural center of gravity. Its industries tend to be more advanced, its people more educated, and its security forces (in the absence of a neighborhood police force) more capable of keeping the community safe – informally, of course.

The second way we control the neighborhood is through our prestige, that intangible respect given to someone because of their reputation for success or influence. In a community of self-interested families, America stands out as unique. We’re also self-interested (and don’t apologize for that), but we are known for building our estate on big ideas like freedom, equality, and justice. We don’t always live up to those principles, but everyone knows that there is at least one family in the neighborhood who aspires to them.

Power and prestige – these two forces put America at the head of the world community. Diminish either one and our influence begins to shrink. Some Americans think that shrinking our influence around the world is precisely what we should be doing these days, but what they don’t know is that shrinking our influence won’t make things more peaceful. It will actually throw the neighborhood into even more disarray.

***

THE PROBLEM is twofold.

First, whether they admit it or not, families in the neighborhood have come to depend on us. Our economic and military might has, over time, become the cornerstone for the neighborhood’s prosperity. Any change in our position – even the perception of a change – sends tremors across the community. When America looks weak, plans change, businesses fold, and families scramble for other means of securing their future. We didn’t intend for things to be this way. It’s just what happened when we amassed more power than everyone else.

Second, America isn’t the only estate in the neighborhood. There are other estates, some less savory, that spend their time plotting to take over. These rivals are rarely driven by aspirations for freedom and justice. Theirs is an ambition far more naked and arguably more sinister than ours. They rarely pretend to have other people’s interests in mind.

The greatest threat to the neighborhood is instability, and the greatest source of instability is the drawdown of American power. It is important to note that our rivals are weaker than us. Their only hope is to occupy voids that result from our neglect. As soon as we pull back from any part of the neighborhood, these adversaries rush in to offer assistance to families left reeling from our sudden disinterest. Nature may abhor a vacuum, but our rivals are dying for one.

The truth is that we never needed to “win” in Syria or anywhere else. We’ve already won. Our foreign policy objective is to preserve what we already have: to maintain, to not lose, to eliminate empty spaces that rivals can fill. The world is already organized according to our interests and it’s in our interests to keep it that way, even if it means spending a little time and money.

Right now our enemies can’t win. They can harass the neighbors, lob bottles over fences, run dirt bikes across the village green in the hopes that we’ll lose our cool. But they only succeed if we lose focus and retreat inside our gates, abandoning the neighborhood to the jungle.

***

THIS IS WHERE limited intervention matters, both as an actual policy tool and a compelling rhetorical image for the public. It’s not about winning; it’s about balancing power to make sure our enemies don’t win. It’s not about containment, it’s about sustainment.

Measured and thoughtful interventions abroad like those in eastern Syria can help increase order and justice in a chaotic world by protecting the neighborhood against entropy and decay. It can keep our enemies, and our friend’s enemies, at bay. And because we operate from a position of strength, we can accomplish a lot with little. Minor expenditures on our part can produce devastating losses for adversaries who stand in a weaker position. We spent a little over $150M on the missiles we fired against Syria (by comparison, in 2016 USAID distributed ten times that amount to countries for environmental assistance alone). What we got in return – the degrading of Syrian military assets and a warning shot across the bows of Russia and Iran – was well worth the marginal cost.

There is also something to be said for the periodic use of force just to show the bad guys that you’re not to be trifled with. The United States is a country of goodwill, but too much goodwill can be a bad thing. Unscrupulous actors take advantage of well-intentioned people, and good intentions must be backed up by visible strength if they ever hope to be effective. Nassim Nicholas Taleb makes this point in his book The Black Swan when he writes, “You can afford to be compassionate, lax, and courteous if, once in a while, when it is least expected of you, but completely justified, you sue someone, or savage an enemy, just to show that you can walk the walk.”

Limited interventions will keep us out of costly, unwinnable fights. In that regard, it is a concept that should resonate with the American people. No one wants a repeat of what happened in Iraq. For that reason, policymakers and politicians should explain to the American people why limited intervention is precisely the right tool for our 21st-century fights. The mission will not be accomplished, by definition – or rather, it was already accomplished in 1945, or maybe in 1991. By moving away from the language of victory (e.g. “winning in Syria”) and recognizing that victory is already ours, Americans will evaluate individual hotspots in the context of a bigger picture. This will foster clarity in the collective mind, manage our expectations, and dispel illusions about what we can and cannot accomplish in the world.

Maintaining order is less sexy than hoisting a flag over Iwo Jima, but that doesn’t make it any less important. Order is a prerequisite of justice, and good neighborhoods are the foundation for a better future for all who live within them.

There are still many strategic, legal, and moral questions to be answered. We obviously cannot fill every void and block every rival. Where and when do we engage? Interventions, military or otherwise, must still be the exception in a neighborhood of fences. Hard power should always be used sparingly. We must respect the sovereignty of other states even as we strive to uphold human rights. We must battle the temptation of empire, that call to constantly meddle in other people’s affairs, but we must recognize that we are the strongest family on the block and our interests and values call for keeping it that way.

Once we recognize this, we must communicate it to the public. Few Americans know why we do what we do in the world, which is why so many call for abandoning the world to its own devices. It is on our leaders to explain why keeping up the neighborhood matters.

I suspect that they’ll find in the American people a ready audience.

Robert Nicholson is the executive director of The Philos Project, a nonprofit organization that seeks to promote positive Christian engagement in the Middle East. He holds a BA in Hebrew Studies from Binghamton University, and a JD and MA (Middle Eastern History) from Syracuse University. A formerly enlisted Marine and a 2012- 2013 Tikvah Fellow, Robert lives in New York City with his wife and two children

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024