Hitler’s Holocaust, surely the most notorious genocide in human history, claimed the lives of an estimated six million innocent Jewish children, women, and men. It also created about three million survivors—victims who escaped with numbers tattooed on their arms and memories of death and depravity etched in their brains. Tom Lantos was one of them—a Hungarian Jew whom Raoul Wallenberg saved, who later became the US Congress’ only Holocaust survivor, and whom I had the honor to serve. Another survivor was Elie Wiesel—also a Hungarian Jew who escaped Auschwitz and later earned the Nobel Peace Prize for the written witness he bore of the perdition he endured.

Both men have passed, as have all but an estimated 100,000 Holocaust survivors. With the loss of their testimony comes the threat that the memory of this manmade hell might fade and atrocity amnesia might befall younger generations. Memorials and museums, such as the US Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, help guard against such amnesia. The state of Israel itself, founded by survivors and their supporters in the aftermath of World War II, is also a living monument to the Holocaust, not unlike the church is to Christ’s crucifixion.

Despite such reminders, surveys suggest that many younger Americans have limited knowledge of the Holocaust, and therefore likely have little inclination to commit our nation to preventing its repetition abroad. In a poll taken last year, nearly one in four US millennials claimed not to have heard of the Holocaust. Forty-one percent believed less than two million Jews perished in it. And fully two-thirds could not identify Auschwitz.

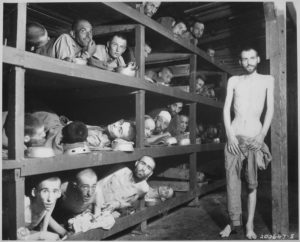

It was such ignorance that Wiesel feared would lead to indifference and tempt the United States—his adopted home—to retreat into isolationism and abdicate leadership in the global struggle to prevent future genocides. Indifference was a leitmotif of Wiesel’s storied life. In his autobiography Night, he chronicled his harrowing journey from the ghettos of his hometown of Sighet to the selection platforms of Auschwitz to the slave factory floor of Birkenau to the frozen tomb of Buchenwald. The young Wiesel’s lifeline throughout this ordeal was his father, to whom he clung. But when his father finally expired at the end of a Nazi’s nightstick, young Wiesel cowered in indifference. Broken, he did not shed a tear. Elie Wiesel’s ministry was a way of atoning for this self-condemning and soul-crushing sin.

In remarks at the White House in 1998, Wiesel expounded upon the indifference that haunted him:

Indifference can be tempting—more than that, seductive. It is so much easier to look away from victims. In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman… Indifference is always the friend of the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor—never his victim, whose pain is magnified when he or she feels forgotten. The political prisoner in his cell, the hungry children, the homeless refugees—not to respond to their plight, not to relieve their solitude by offering them a spark of hope is to exile them from human memory. And in denying their humanity we betray our own.

The United States reached a milestone in overcoming indifference and realizing Wiesel’s vision of vigilant leadership in the fight against genocide with enactment earlier this month of a law bearing his name. The Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act, supported by majorities of both parties in Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump, outlaws indifference by directing our national security and intelligence gathering agencies to assess and address the threat of genocide and other atrocities occurring around the world. It institutionalizes the Atrocity Prevention Board (APB), an interagency committee which President Barrack Obama formed in 2011 by executive order. And, importantly, this law states unambiguously that “prevention of atrocities [is in the] national interest.”

Instrumental to the bill’s passage was support from the faith community. Seventy-two Christian, Jewish, humanitarian, human rights, and other organizations—including The Episcopal Church, to which I belong, and the Philos Project, a co-publisher of this journal—joined in advocating for it. The significance of this solidarity can only be appreciated against the backdrop of the church’s theological ambivalence toward atrocity prevention. When defense of the faith was at stake, as during the Crusades, Christians have during their two-thousand-year history been complicit in atrocities under religious pretense. The just war tradition, as developed within the church, has resisted such evil, however. It’s in bello criteria calls for both discrimination—sparing innocents—and proportionality—using no more force than necessary. Genocide violates both principles in its targeting of an entire race or ethnic group, innocents included, for extermination. It is inherently indiscriminate and disproportionate. Genocide represents the antithesis of the just war.

Having helped secure its passage, the faith community should now turn to supporting the work of the APB—and holding the administration accountable for obeying the letter and spirit of the law that brought it into being. There is reason to doubt it will. National Security Advisor John Bolton, who will supervise the interagency body, has long been an outspoken critic of the United States assuming moral commitments, such as the Responsibility to Protect, which challenge traditional definitions of the national interest. And President Trump’s “America First” foreign policy fetishizes sovereignty and does not lend itself to US global leadership to protect innocents other than Americans. But the administration deserves credit nonetheless for enshrining the nexus between American values and interests. In the extreme case of genocide, at least, it has recognized a higher duty.

On last year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day, President Trump said in a statement that “we have a responsibility to convey the lessons of the Holocaust to future generations, and together as Americans, we have a moral obligation to combat anti-Semitism, confront hate and prevent genocide.” In signing the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocity Prevention Act, the president shows he means to make good on this moral obligation. His implementation now of this landmark law will prove if he indeed will. In outlawing US indifference to genocide, the president and the bipartisan, faith-based coalition beside him have made a difference.

—

Matt Gobush is a contributing editor to Providence and previously served on the staff of the National Security Council during the Clinton administration, the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, and the US Senate. He currently serves on the Standing Commission for World Mission of the Episcopal Church. Matt works in the private sector and lives in Virginia with his wife and five internationally adopted children.

Photo Credit: Elie Wiesel in 2009. By Veni, via Flickr.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024