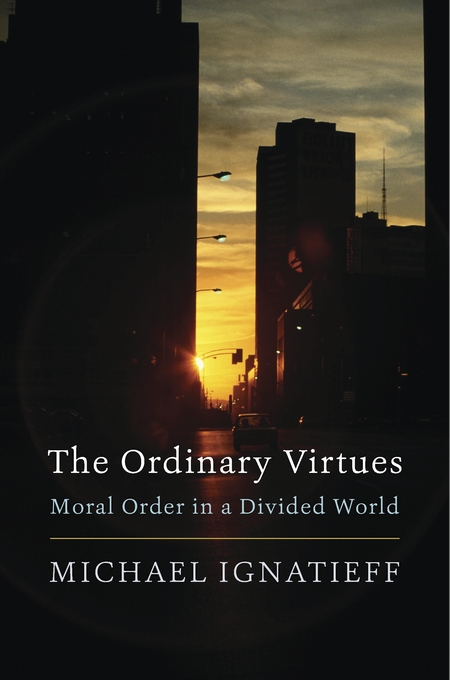

Is globalization strengthening shared moral values and behaviors among nation-states? Michael Ignatieff, who has written many journalistic and scholarly books on international political ethics, addresses this question in his most recent book, The Ordinary Virtues: Moral Order in a Divided World. The research, which involved a three-year investigation in numerous countries, was underwritten by the New York City-based Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs to commemorate the organization’s centennial.

The study’s goal was to determine whether or not increasing international economic and social integration is strengthening global morality. The aim was not to discover how people in different cultures and economic communities think about moral rights and duties, but rather how they behave when confronting challenges of human existence.

The research focused not on ethical metaphysics but on people’s everyday moral behaviors that make living in challenging circumstances tolerable. Ignatieff terms these behaviors “ordinary virtues,” and they include such attributes as trust, tolerance, forgiveness, reconciliation, respect, and resilience.

The study’s goal was to determine whether or not increasing international economic and social integration is strengthening global morality. The aim was not to discover how people in different cultures and economic communities think about moral rights and duties, but rather how they behave when confronting challenges of human existence. The research focused not on ethical metaphysics but on people’s everyday moral behaviors that make living in challenging circumstances tolerable. Ignatieff terms these behaviors “ordinary virtues,” and they include such attributes as trust, tolerance, forgiveness, reconciliation, respect, and resilience.

To carry out this study, a Carnegie team visited different urban centers in the United States and traveled to Brazil, Bosnia, Japan, Myanmar, and South Africa to explore how citizens are confronting issues like unemployment, corruption, ethnic dislocation, citizen-migrant tensions, and restoration of trust after ethnic violence and war. Although cosmopolitan elites rely heavily on abstraction in identifying and applying legal and moral principles to their lives, Ignatieff found that the people he met did not rely on theoretical principles to deal with their common needs and wants. Instead, a person’s moral life was rooted in the specific challenges of everyday life. Ordinary virtues emerged as people sought to make life morally meaningful in their own communities.

Although international law may have helped to conceptualize human rights, Ignatieff finds that the common folk in poor communities and developing nations do not rely on abstract legal and moral claims. Rather, the moral life is rooted in the local, specific challenges that people commonly face in their neighborhoods. For the vast majority of people, the moral life arises not from human rights universalism but from their responses to the challenges of poverty, unemployment, corruption, violence, and discrimination. Ignatieff writes that “the most striking feature of the ordinary virtue perspective is how rarely any of our participants evoked universal principles of any kind…and how frequently they reasoned in terms of the local, the contingent, the here and now, what they owed those near to them and what they owed themselves.”

Even though people may not rely on universal human rights rhetoric to guide their specific decisions, Ignatieff argues that the structure of global human rights has contributed indirectly to global solidarity by providing a foundation for people’s ordinary virtues. The basis of these virtues is the universal claim of human equality—namely, “that all persons are entitled to respect and a fair hearing” and that “no one’s view must prevail by virtue of their race, gender, religion, creed, income, or nationality.” Although globalization may be dividing the world and fracturing communities, the belief in “equal voice” provides a moral basis for the emergence of ordinary virtues.

Regrettably, equality of voice does not assure peace and prosperity—or what Ignatieff terms “a chorus singing in harmony.” Instead, the foundation of moral equality provides a structure for the development of a minimal social and political morality. Ignatieff explains that “what human beings share, everywhere, is not a language of the good or a global ethic, but instead a common desire, in their own vernacular, for moral order, for a framework of expectations that allow them to think of their life, no matter how brutal or difficult, as meaningful.”

In his exploration of moral life in Bosnia, Brazil, Japan, Myanmar, and South Africa, Ignatieff finds that developing just and humane social and political communities is not inevitable. This is so because ordinary virtues are in a continual battle with ordinary vices—greed, corruption, predation. Can anything be done to strengthen virtues and diminish vices? Ignatieff thinks so. He argues that the state and, more specifically, public institutions can play a pivotal role in empowering ordinary virtues. While elites may believe that government is the source of injustice and evil, Ignatieff writes that “it is a fantasy to believe that if only the fetters of the state could be removed from daily life, ordinary virtues would flourish.” Instead, he argues that liberal, democratic institutions are best able to contribute to the nurturing of such virtues. If public institutions do not treat their people with respect and decency, it is unlikely that people will be inclined to compassion and decency toward fellow citizens and especially toward strangers. Nurturing decent public institutions is therefore critical in advancing a more humane world.

In his book Thick and Thin, political philosopher Michael Walzer differentiates the “thick” morality found in states and small communities from the “thin” morality in the international community. Global morality is “thin,” he suggests, not because it is less important but because it is more general and diffuse. To a significant degree, Walzer’s claims are renewed in The Ordinary Virtues since Ignatieff demonstrates that the shared moral dispositions and behaviors that arise from everyday challenges foster a “thin” global morality. Such morality, expressed through ordinary virtues, has contributed to a meaningful, tolerable life in difficult circumstances such as South Africa after apartheid, Bosnia after the ethnic wars of the 1990s, and Fukushima after the nuclear disaster in 2011.

In view of Ignatieff’s finding that people are likely to be influenced more through specific local initiatives than through programs that seek to advance claims rooted in legal and moral universalism, how should US diplomacy seek to advance human rights and prosperity? To begin with, US officials must remember that since fundamental beliefs about human dignity are rooted in a culture, the task of cultivating human rights presupposes a moral-cultural order favoring liberty, equality, and toleration. Developing such a cultural system is of course a project for many generations. Additionally, in advancing human dignity US officials must pay attention to the cultural context in which rights are being advanced. This means that officials must have deep knowledge of the common habits and cultural traditions of the recipient society if they are to advance values and habits conducive to freedom without triumphalism. Ultimately, however, creating and sustaining peaceful and prosperous communities is an indigenous task. It is the duty of citizens working in their own communities as they pursue proximate justice through the intuitions and dispositions expressed through ordinary virtues.

Mark R. Amstutz, a Providence contributing editor,is professor emeritus of political science at Wheaton College. He is the author of a number of works, including Evangelicals and American Foreign Policy; Just Immigration: American Policy in Christian Perspective;and International Ethics: Concepts, Theories, and Cases in Global Politics,now in its fifth edition.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024