The timeless role of East-Central Europe

While Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine shocked the West, for East-Central Europe it was not a surprise but a return to the familiar theme of invasion and imperialism from outside powers. As the late historian Oskar Halecki reminds us, the historical role of the region, with its small states, has been to fend off foreign political and military interference, particularly from the East. Thus, they politically strive “to be associated […] with the western democracies” and “to be included in the Atlantic community, which is not a geographical expression but a spiritual conception, and […] the main pillar of a better world order in the future.”

This political desire rests on the feelings of cultural belonging to the West exhibited by East-Central European nations. The tragedy of East-Central Europe during the Cold War, according to the late Czech novelist Milan Kundera, was to be politically cast off into a different civilization. Their struggles served the survival of their nations and the preservation of their Westernness. This was tragic because it was unappreciated: in terms of culture, few took notice that “these countries vanished from the map of the West.” In fact, Halecki made a similar observation earlier in his book Borderlands of Western Civilization when he lamented that little attention was given to the history of nations that repeatedly stood between the West and invasion from the Ottomans and Russians.

The civilizational factor is crucial. In Politics and Culture in International Relations, the late political scientist Adda B. Bozeman wrote that “Central and Eastern Europe was terra incognita” (unknown land) in the eyes of US decision-makers at Yalta. However, by the turn of the millennia, Washington led the way in re-uniting the West: a year before inviting seven East-Central European countries to NATO in 2002, President George W. Bush spoke in Warsaw about Europe and America being “products of the same history, reaching from Jerusalem and Athens to Warsaw and Washington. We share more than an alliance. We share a civilization.” In 2017 President Donald Trump also spoke in Warsaw about defending Western civilization, but received mixed reactions, reflecting divisions over what is meant by “the West.”

Conserving the “West”

Following the Cold War, an interesting philosophical debate has ensued between two competing conceptions of Western identity. On the one hand, Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” and globalization showed the triumph of Western power and values; on the other hand, Western ideas cannot expand beyond certain regions and cultures, as highlighted by Samuel P. Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” theory. But even without reference to the inevitable expansion of “Western” values, the cultural and political trajectories of the West seem to be diverting. While the influence of Western political and economic institutions have come to dominate power politics across the world, the concept of “Western civilization” has disappeared from academic studies and public discourse. As political scientist James Kurth pointed out in 1994, the real clash of civilizations is fought not with non-Western forces outside the West, but with post-Western forces within the West.

The competition of key sources of Western thought, and particularly the dominance of the Enlightenment tradition over the Classical and the Christian traditions reflects certain fault-lines among conservatives in the United States. One can divide American conservatives into several groups using various labels, but in recent years two main camps emerged: the Establishment Conservatives and the New Right. The former emphasize free markets and national security issues, hence they are often coined libertarians or neoconservatives, whereas the latter is more keen on issues of culture and national sovereignty, thus associated with the (new) traditionalists.

Without discussing their backgrounds (elaborated by Matthew Continetti’s The Right), or the main conservative foreign policy principles (reviewed by Colin Dueck’s Hard Line), it is clear that the two camps focus on different dimensions of the West. For Establishment Conservatives, the West stands for a network of international political, security and economic structures arranged around the transatlantic partnership. For the New Right, the West rests on a set of European and American intellectual and spiritual ideas tied to particular areas. The essence of their internal friction is that the former camp’s economic and security policies potentially undermine traditional pillars of the social fabric. Although this was managed under an anti-communist fusion during the Cold War, today’s geopolitical environment is yet to pose a mutually acknowledged common foe.

Challenges and opportunities on the borderlands

The end of the Cold War was a crucial development in terms of civilization and geopolitics alike. In Bozeman’s words, East-Central Europe’s recovery was an “epochal victory of Euro-American West” shadowed by the fact that “chief policymakers in the United States had not been prepared for it.” According to leading scholar of the liberal international order G. John Ikenberry, the enlargement of Western institutions was a crisis of success because the Western order quickly filled the global power vacuum left by the Soviets, with new (and newly restored) members of the Western community having different expectations.

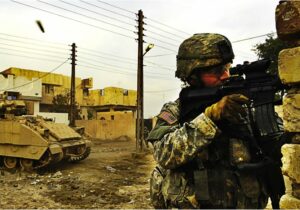

Indeed, the nations of East-Central Europe entered NATO for the sake of territorial defense and soon earned the moniker “new Europe” from Donald Rumsfeld for being more supportive of the Iraq War than “old Europe” (France and Germany). Now, East-Central Europe has gained real significance with the war in Ukraine. In fact, the conservative notion that NATO’s center of gravity has moved eastward and “now stretches from Helsinki to the Black Sea” verified Halecki’s idea of an East-Central Europe defending the West from the East.

But culture still matters. Kundera’s lament over the region was not just about its erasure from Western memory. East-Central Europe’s bonds to the West were Western Christianity and culture, hence they always carried “something conservative, nearly anachronistic: they are desperately trying to restore the past, the past of culture, the past of the modern era.” However, in the meantime, both religion and culture “bowed out” in Western Europe. Hence, the real tragedy of East-Central Europe is that it believes in a West that may no longer exist. Some of these longings take the form of neo-traditionalism on the right often associated with illiberal populism (as in America). Yet traditional values and culture are important because they helped to preserve national and Western identity in the first place.

The desire for a rebirth of Classical and Christian traditions in the West is not merely the pipe dream of a few intellectuals. Today’s geopolitical competition may not be the same as the that of the Cold War, but it is still a competition for hearts and minds. The West, and especially America has a great heritage of soft power in East-Central Europe which experienced both extremes of moral relativism through fascism and communism.

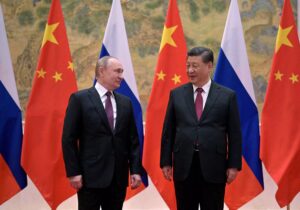

Yet the oikophobia of the West, begun during the Enlightenment and continued today by radical progressives, is not attractive to those who spent decades under totalitarianism defending their particular cultural identity; quite the opposite, it is regarded as a pointless cultural suicide and a betrayal of those who struggled and resisted to preserve their culture. A coherent, attractive view of Western civilization is also needed to protect from malign outside influences. Authoritarian and anti-liberal ideas from Russia and China have purchase among Western traditionalist because their own values were cast aside. It is a geopolitical interest to focus on both the politics and the culture of the West, with its borderlands offering telltales for success and failure alike.