As the debate raged over the recent foreign aid package, legislators and other public figures derided the bill with a familiar refrain: Ukraine is becoming another “forever war.” These conflicts, say their critics, are purely meant to enrich the military-industrial complex while maintaining the outermost frontiers of the American empire. The idea of endless warfare as the norm for American foreign policy is not new, being repeated ad nauseam for the past two decades. Yet there is no such thing as a forever war – and those who utilize this phrase only expose their own ignorance of the length and intensity of most conflicts across history.

The term has been used sporadically since the 1800s, but exploded in popularity after September 11, 2001 and the consequent War on Terror. The term quickly gained purchase to refer to the long conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, becoming ubiquitous in media. But the chronic use of “forever war” does not mean it is accurate in either the present or historical context.

The word ‘forever’ is not a useful descriptor, as nothing is actually interminable. Still, simply calling something ‘long’ doesn’t have the same ring to it. As attention spans decline, the definition of ‘long’ itself regresses to nothingness, making the “forever war” idea even more absurd. The phrase falsely equates duration with failure, which belies the truth of serious conflict. Lengthy occupations with extremely low levels of active combat are often how wars end successfully. Pacifying an enemy population does not happen overnight, nor does replacing a defeated government with a friendly one. But time, as history has repeatedly shown, is necessary for victory.

As long as history has been recorded, wars generally have not been tidily wrapped up in a year or two. The Greeks and Romans, the ancestral forebears of the modern West had their fair share of supremely long wars, ones that would shock the present-day “forever war” critics.

The famed trio of Greco-Persian Wars stretched for nearly 50 years with only a few short pauses in between. The intra-Greek Peloponnesian War lasted 27 years and absorbed all of the energies of the Hellenistic world. Republican Rome mobilized for three massive wars against its nemesis Carthage, which lasted a total of 43 years. But the Punic Wars pale in comparison to the series of Roman-Persian Wars. These intermittent conflicts covered the period from 54 BC to 628 AD – a whopping 681 years. The fighting did not continue unabated, but it popped up enough to be considered the major geopolitical rivalry of the era. Regardless, the fighting eventually stopped.

America has had its own long wars before the 21st century. The Korean War, fought between 1950 and 1953, never technically ended. Despite an armistice, North Korea has not renounced its irredentist claims and tens of thousands of American troops remain in the South. This sounds like a forever war, yet nobody is calling for a withdrawal from South Korea; perhaps because the continued American presence has created a thriving ally while preventing another invasion. The Cold War was the constant backdrop to nearly half a century of geopolitics. In spite of its name, the Cold War repeatedly turned hot and seemed totally interminable. In 1991, though, it terminated with a Western victory, notwithstanding the efforts of doves, fellow travelers, and useful idiots.

When the proponents of forever war make references to the past, they eschew these contrary examples and focus on the ideal American conflict: World War II. For us, it lasted less than 4 years and ended with unconditional surrender and postwar occupation. Germany was partitioned, its ideology defeated, and its genocide ended. Japan had two nuclear weapons dropped on it, lost the right to an offensive military, and was occupied by Allied militaries until 1952. The aftermath in other areas was more complex, but the defeat of the main foes was total. This was exceptional and is not the norm of armed conflict in Western history.

Even though history is full of long wars that eventually ended, that does not preclude the possibility that America’s modern wars – Afghanistan, Iraq, and now Ukraine – are indeed “forever wars.” But none of those conflicts were or are everlasting, nor would they qualify for the critics’ definition of a “forever war.”

Critics claim that Afghanistan was a guaranteed debacle with no victory condition, merely a sinkhole for American lives and dollars. But Afghanistan was neither unwinnable nor endless. America won the major combat phase of the conflict, satisfied its objectives of deposing the Taliban and degrading Al-Qaeda, and steadily reduced troop presence. Was there still minor fighting at the time of withdrawal? Yes, but this was largely handled by Afghan forces and was increasingly cost-effective. As of 2021, our mission was essentially a policing operation, ensuring relative calm and preserving our interests.

We chose failure in Afghanistan; we lacked the willpower to retain a small supporting force for the long term, we refused to address the root of the Taliban problem – Pakistani support – and we failed to convince the American people that the mission was worthwhile. And it was worthwhile; we have already seen a return of terrorist entities operating there and carrying out attacks abroad, as well as a greater Chinese presence in this key region. In our two decades in Afghanistan, America saw no major terrorist attacks emanating from this nation – a massive feat considering most assumed that large-scale Al-Qaeda attacks would become commonplace. We bought domestic peace at what became a low cost by 2021, but chose to throw it away.

The war in Iraq is treated similarly, but again, the critics have it all wrong. As with Afghanistan, we won the major combat phase of the war rapidly, defeating Saddam Hussein’s army and ending his totalitarian regime. Our later choices prolonged the conflict and necessitated further American involvement. Still, after the surge in the late Bush administration, Iraq was largely pacified and a continued deployment of fewer troops would have been sufficient to ensure long-term victory. Unfortunately, President Obama chose to claim victory too soon and withdrew American troops entirely. This was a serious error that allowed ISIS to build its territorial ambitions, start another war, and carry out terror attacks on US soil. This, unsurprisingly, required a redeployment of American military assets to Iraq, something that was completely avoidable had we not left in the first place.

With regards to Ukraine, the “forever war” case is even weaker. The war in Ukraine differs from the Afghanistan and Iraq scenarios in many ways, all of which militate against the moniker “forever war.”

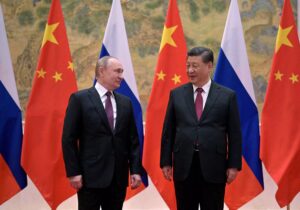

First, and most importantly, the United States is not directly involved. We have provided military and humanitarian aid, as well as intelligence support, diplomatic backing, and combat training. What we have not done is send American troops to fight. In that respect, this should not even count as an American conflict. Additionally, Ukrainian war aims are consistent and measurable: ejecting Russian troops from all its territory. This may be a challenge, but it leaves very little room for mission creep. The stakes for Ukraine – and Europe more broadly – are enormous. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were wars of choice. That does not mean they were unjustified, but that America could survive in the long-term had they not been undertaken. If Ukraine chose not to fight against Russia, the country would cease to exist. Russia’s stated war aim is to unmake Ukraine as a nation-state and revise the territorial settlement that ended the Cold War. That does not only center Ukraine in the crosshairs, but Moldova and the Baltic states – the latter being NATO allies – too. Not only has the war in Ukraine been going on for a short period of time, it has all the makings of a conflict that could destroy the European security architecture and undermine critical American interests. In these respects, the term “forever war” is completely absurd.

There is one major problem with the American security posture that does lend itself to the charge of “forever war,” and fixing it would completely neuter the argument of these critics. Going all the way back to the Vietnam War, the American foreign policy apparatus has completely forgotten how to win. It has become totally allergic to victory and what is necessary to achieve it. Victory – real, permanent victory – requires long-term sacrifice, civilizational willpower, domestic buy-in, and cultural confidence. In the 21st century, the age of immediacy, we lack these attributes. This is part of the reason that so many in the liberal foreign policy establishment seem terrified of Israel’s approach in Gaza: they seek victory, not temporary quiet. Victory can look messy and takes time, neither of which the “forever war” critics seem to understand or accept. Unilaterally ending a “forever war,” which is what they seek, is colloquially known as “surrendering.” If they are to have their way, there won’t be any more “endless wars,” but there will be just as few American victories abroad. We must not allow that to happen.