June 6, 2015

Richard Dreyfuss

to Susannah Black

Susannah,

First, thank you for taking me seriously; I was just about to have a need for an anger management seminar; my fear for my children’s welfare which translates to my nation’s welfare has been met with so many nods of agreement and nothing else that I want to scream. So for that alone I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

I think I have a response which may sound like ‘yeah, but–‘ but isn’t quite that. I agree that having a strong robust spiritual life reflected in our daily behavior and the simple instinct toward ‘good acts’ is desperately needed, and I have always believed in tikkun ‘olam, which is the Jewish mandate to repair the world.

But first things first: if we don’t shore up the structure of shared beliefs in the values that are certainly born in Christianity and Judaism and translated into governance by applying the ideas of the Enlightenment into law, we will lose the law, the values, the freedoms that are strong enough to contain differing beliefs about God and His place.

I once brought my father into a work situation where there was lying, cheating, personal betrayals and such. On the line was the future of a club and an improv group; we were confused and didn’t know the right set of priorities; he listened to a lot of hollering and finger-pointing, all of us aware that the our endeavor was being sunk. Then he said, “Guys, a house is burning. First put out the fire, then you’ll be free to fire, or hire, or change your methods, but your first obligation is to remember your house is burning. You will all have nothing if it burns to the ground.”

So that’s a way of saying I welcome your statement that ultimately we have to remember (if I got this right) the spiritual space in our founders’ lives, or in the society they were working from. And believe me when I say I want a strong and respected connection to that mysterious and beautiful part of us, and grieve at its lack of core strength; but a house is burning, a structure that was as close to a political miracle as there has ever been. When that urgent fire is put out, and we are strong enough to proclaim our pride in our unique structure of governance; when our belief in our founding documents and our confidence in ourselves is well tuned and ready to do battle with an ideology that I can’t believe shares natural law with you; then we can at the same time strengthen our churches and apply what we receive from them to the battle at hand.

But don’t think we must enrich our Western spiritual heritage before we revive our civic culture, or else we’ll sink into Santorum’s and Huckabee’s “This is a Christian nation” misreading of American history. That leads to a position as bad as those who blindly support Israel: leads you down the path to defending the morally unacceptable. We are a nation of different cultures, and our civic culture is meant to sustain all of them, while offering their bearers the ability to become Americans. This culture respects individuals, offers them mobility, the right to change their minds, the right to worship—not as adherents to weak “everything is relative” modern religions but those with strong statements about rights and wrongs. These believers may differ with one another at their foundations, but they allow that God has made those differing opinions and they know that we’re arguing only over His name.

About natural law I include myself out of any position until I learn more, understand more. I do know that our country is strong enough and smart enough to have room for deists, agnostics, and atheists, for social conservatives and structural conservatives, for liberals and progressives and Rand Paul, whom I happen to like. But it, the country, is off-track, out of sync, and we’re running out of time. Mark Steyn, a writer with an irritating case of the smart-alecs, has written a book I urge you read called America Alone. Just the first few chapters are a geo-political wake-up call, and he is not someone I agree with very much. But he quotes bin Laden: “When people see a strong horse and a weak horse, by nature they will like the strong horse.” And he quotes Donald Rumsfeld: “If we know anything it is that weakness is provocative.”

We are on a clock we don’t see or comprehend. We will not survive this century unless civic virtue is revived. We can discuss its origins all day—if we have the right to speak at all, and aren’t dead under jihad.

Again, I always knew we had to talk about all this eventually; we’ve both felt that connection. I love and respect you, and want you to be on my side and know that I am on yours. I may disagree with what you say but I will defend to the death the fun we both have when we talk.

———————–

Susannah Black

to Richard Dreyfuss

June 6, 2015

Giant hug. I will respond with more coherent things later.

———————–

Richard Dreyfuss

to Susannah Black

June 7, 2015

I have a hunger for this exchange. Make it a priority, with respect.

———————–

Susannah Black

to Richard Dreyfuss

June 9, 2015

Patience, grasshopper.

P.S. Am going to see On the Town tonight! V. excited.

———————–

Susannah Black

to Richard Dreyfuss

June 13, 2015

OK! Back into it!

Hmmmmmmmmmmm. OK, I’m writing to explore these ideas, not to prove anything or put forth a final answer (although there are some things I’m pretty sure of) so bear with me! I’m trying to get at truth, at reality, as I write, and so the “religious” angle is going to come up—not because I want to promote “my position” against others, and not because I think it’s good for America, or that America was founded as a Christian nation (it manifestly wasn’t) but because the reason I am a Christian is that I believe this stuff is true, and so pretending I don’t think it’s true when I start thinking about politics just doesn’t make sense. That’s just an opening caveat—to explain why I might be hauling God into this conversation. Burning bush or baby in Bethlehem or factor in our political theories: one thing you can say about the God of Abraham, He does tend to show up.

That said, here I go:

It’s not so much, for me, about “getting back to the Founders’ vision.” First of all, I think that to project a completely unified vision on them is massively oversimplifying, because they disagreed with each other on a lot. Second of all, with regard to what they agreed on, I don’t necessarily agree with them.

But the main thing is that I don’t think politics can save us. Living in an orderly and just, non-arbitrary and non-oppressive “city” (i.e. political community) is a great good, and one that we should strive for. I’m still making up my mind about, trying to think through, what role politics and the life of the city should play in a good human life—Aristotle thought it was essentially the highest calling available to humans, and some of the Founders were certainly Aristotelians in this sense. And I believe that it probably has a role in everyone’s life: that “public life” is something that everyone should do, in some way, however badly (though we don’t all need to take the same roles in that life—i.e., we don’t all need to run for office, and I’m not even completely convinced that voting is the bare minimum; I think that voting is probably neither necessary nor sufficient for good civic engagement). In other words, I think that we are probably all called to be “civic” in some way, but that it’s not true that republican democracy is the only way that should look, across all times and places. Although it’s what we’ve got, and that’s fine.

Traditionalist conservatives like Russell Kirk are very, very suspicious of public life in general—and even, therefore, prefer the life of the country to that of the city, because in the country, you can at least in theory (if you have a farm and maybe some farmhands or strong sons) be self-sufficient. I am a city girl, as you know, and I don’t share the anti-political feeling of these folks.

But I think that the truth of the matter is that we stand in relation to politics very much as we stand in relation to romance (and to parenthood or family life or friendship, but let’s start with romance).

We have a deep passionate un-eradicable conviction that both politics and romance are necessary things in our lives, that most human lives should include both civic concerns and a husband or wife. And we’re right. The way the Bible talks about both politics and marriage is that these are human things, which are both good in themselves, and are lived symbols of bigger things. The relationship between God and Israel (and between Christ and the Church, which amounts to the same thing) is presented as a romantic relationship: the culmination of the messianic age, what God’s plan is heading for, is called “the marriage supper of the lamb” in the New Testament; in the Old, the Song of Solomon is both an a celebration of a specific courtship and wedding of a specific Israelite king, and also an allegory for God’s courtship of and love for Israel.

Similarly, the relationship of God to Israel, and Christ to the Church, is described in political terms: He is a King; we are “citizens” of his society. Our end, our final state, in Christian theology, is not a disembodied “heaven” and not a return to the non-civic garden, but is life in a city: what’s called the New Jerusalem. Christianity and Judaism, just as much as Greek philosophy—perhaps even more so—present man as a political being. We are called to bear God’s image as rulers (under Him) of our own areas of stewardship—which includes taking care of and being generous with our own property; stewarding our time and talents for the good of ourselves and others; and taking political responsibility in whatever role is appropriate for us in our “cities,” our communities, whatever they are.

But just as a marriage can go wrong if you take the smaller and contingent coupling as the bigger and eternal one, so politics can go wrong if you take political life here as salvation. Our cities here are deeply important—how we live in them and help to shape them is eternally important—and all the good that we do here will last into eternity, and be taken up into the civic good of the New Jerusalem. But still, we are not called on to, and we have no ability to, create a perfect society or city here by our own efforts or for our own glory—and things go wrong, very wrong, when we forget that. Such utopias necessarily exclude God and other good parts of life: politics becomes “total,” obliterating family life and art and all other partial goods; that’s why these societies are called “totalitarian.”

But—I can hear you say—do we even need to figure all this out? Isn’t the virtue of the American system precisely that it provides a playing field where Susannah can believe and think about this, and someone else can believe and think about other stuff, and we’re still bound by a sort of Enlightenment minimum of civility?

Well, yes—that is good, except for a couple of things.

First, if what I believe about all this is true, it’s important. And it’s either true or it’s not.

Second, the Enlightenment minimum that the Founders wanted to operate on implies a whole lot of questions that you can’t take seriously without getting sucked right back in to all this “mystical” or “metaphysical” stuff. For example, what does it mean to say that all men are created equal? Why do you think that’s true, where does that equality come from, and in what does it consist? What does it mean to say that a law is just? Is there a standard you’re measuring this law against, and where did that standard come from? When you say that something is “morally unacceptable,” what do you mean specifically, and where does that come from? If someone says, OK, you like societies where people don’t have their throats cut on the beach for practicing their faith and aren’t forced to marry against their will, but I like IS’ application of sharia… what would you say? Is it a matter of taste? If not, what is it?

I’m asking you, Richard, for real—if you’d like, I’d love to hear what you think about these specific questions, as well as any other thoughts about all my mystical weirdness above.

Love,

S

P.S. are you aware that your son follows your stalker on Twitter? You know, that guy who made the I Really Want to Meet Richard Dreyfuss music video. There’s something pleasingly circular about the fact that Ben follows him.

——–

Susannah Black received her BA from Amherst College and her MA from Boston University. Her work has been published inFirst Things, The Distributist Review, Front Porch Republic, Ethika Politika, and elsewhere; she is a founding editor ofSolidarity Hall. She blogs at radiofreethulcandra.wordpress.com and tweets at @suzania. A native Manhattanite, she is now living in Queens.

Richard Dreyfuss was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1947 and began his acting career at the Los Angeles Jewish Community Center when he was eight years old. He began doing features in roles of size in the early 1970s in films such as American Graffiti, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and Jaws. He won the Oscar in 1978 for his performance in The Goodbye Girl. He has been acting in American theatre, television and film for over 45 years. In his personal life, Dreyfuss has undertaken a nation-wide enterprise to encourage, revive, and enhance the teaching of civics in American schools. He has become a spokesperson on the issue of media informing policy, legislation, and public opinion, speaking and writing to promote privacy rights, freedom of speech, democracy, and individual accountability.

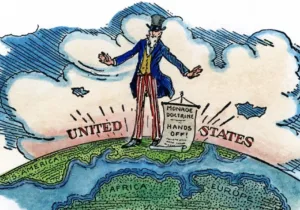

Image: Elihu Vedder, Government, 1895. Library of Congress/Thomas Jefferson Building