As someone who studies religion and politics, I shudder at what the next 11 months will bring. The Biden and (presumably) Trump campaigns will relentlessly demonize each other with the knowledge that fear and anger, rather than dry policy discussions, drive voters. No mere contest of policy and ideas, the 2024 election will be presented by both sides as the be-all-end-all moment in American political history—the point at which our country plummeted into Dante’s inferno or ascended (or perhaps in Trump’s case re-ascended) to utopian heights. Social media will be a dumpster fire of snarky memes, conspiracy theories, and self-righteous pontificating. For the average citizen, this will be the emotional equivalent of a marathon, verbally abusive, argument that leaves you enraged, terrified, and exhausted—the kind of argument that drives people to end their marriages or lives. The election outcome, whatever it is, will bring a wave of unrealistic hope for one side and a wave of unmitigated terror for the other.

America’s pulpits will generally ignore the slow-motion train wreck occurring around them. It will be the elephant in the room that goes unacknowledged as they continue with their regularly scheduled programming. Church hallways will be filled with tittering, headshaking, political discussions that end once you enter the sanctuary. Social media dogfighting will pause until the benediction is over. There will be some exceptions, of course. A round of “issues” sermons will be preached—most commonly on abortion or sexual orientation. Pastors will make a biblical case for certain positions and then, with a shrug, claim they are not telling you who to vote for but just making it clear where Jesus stands on these issues. There will also be a smattering of “character” sermons—some of which will be bold enough to explicitly reference Trump’s moral shortcomings. These will trigger outraged cries of heresy which quickly precipitate backpedaling “clarifications.” In late October/early November, a select few pastors will go all in and preach the 2024 campaign as the be-all-end-all moment in American political history—a campaign speech with Biblical proof-texting that makes the rounds on social media.

I submit to you that these are not the political sermons American Christians need in 2024. One more “issues” sermon is unlikely to change someone’s view. One more “character” sermon is unlikely to point out flaws that are not already blindingly obvious. The “voters in the hands of an angry God” sermons merely pour gasoline onto the fire. Voting inevitably involves weighing and balancing of differing values that are widely shared in society and, for this reason, the Church has never formed a consistent consensus on what constitutes “Christian” political views. Whom someone votes for on election day will be a reflexively easy decision for most and an agonizing, soul-searching experience for a select few.

American Christians need different kinds of political sermons in 2024. The current political environment gives rise to a number of questions Christians, to varying degrees, will be wrestling with. Moreover, these are questions the Bible directly speaks to and pastors can help their congregations navigate these struggles.

How do we “fear not” during such fearful times? How do we not let the “sun go down” on our political anger? Recent articles in First Things asserted that America was “repaganizing” and questioned whether some sort of Protestant military coup was inevitable. The mere mention of such things indicates the level of fear and anger the church is wrestling with. The Bible is replete with examples of God’s providence during times of political turmoil that speak to our current fears and anger. Most of the Old Testament prophets lived in turbulent political environments and they provide examples of the faithful living during uncertain times.

How do we love those we fear or hate? Limits on in-person worship services imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic triggered multiple lawsuits between Christians and their governments. In one notable case, megachurch pastor Ché Ahn charged the State of California with curtailing religious freedom, and the Supreme Court eventually ruled in his favor. On January 6, prior to the Capitol riots, Ahn would encourage a crowd of protestors to rise up and throw out “Jezebel.” Anger and fear are natural reactions towards those who mean us harm (or who at least we perceive to mean us harm.) The Psalms express the struggles of the faithful with fear, and anger. Forgiving others is likewise central to the Gospel message.

How do we love those who fear or hate us? Some in our society feel deeply threatened by Christian Nationalism and the broader role Christians play in politics. These sentiments are an obstacle to ministering to non-believers. The persecution endured by Christ and the early Church serve as examples to loving those who fear or hate us.

What if other Christians denounces our political views as sinful or even heretical? What if we believe another Christian’s political views are sinful or heretical? Our nation’s current political divisions bisect the Church. Christians are calling each other to “repent” of their sinful political views and denouncing each other as unsaved heretics. Paul wrote about divisions within the church that can guide us today.

Should we engage in politics? How should we engage in politics? A 2022 piece criticizing Tim Keller and the “winsome” approach to political engagement triggered fierce debate over how Christians should engage in politics. The question goes beyond voting and political activism and encompasses social media habits and dinner-table political debates. It is tempting, and perhaps even wise at times, to simply change the channel or change the subject. Political doomscrolling can merely trigger more fear and anger. And yet, to completely abandon the field of politics is to abandon a field of ministry. Engaging in politics in a godly manner is not unlike engaging in any other vocation in a godly manner—replete with unique challenges and opportunities. The Bible has much to say about respecting authority, edifying communication, conflicts, and focusing on what is wholesome. These passages can guide Christian engagement in politics.

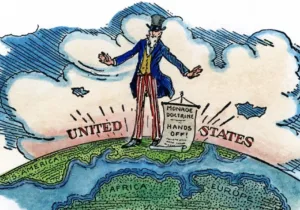

History teaches that religion and politics are a volatile mix. The American Revolution and the Civil War both deeply and violently divided the American church. Mainline churches never fully recovered from the Social Gospel movement’s collapse amid the horrors of World War I. The Cold War triggered religious resurgence while the fall of the Berlin Wall triggered religious decline. Likewise, the rise of the Religious Right may be connected to the rise of the “nones.” We have yet to see how the advent of Christian Nationalism will affect the Church. We need pastors to directly speak to the very real political questions Christians are facing and shepherd God’s people through our own volatile times. Pastors should also know they are not alone.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024