Due to the Iron Curtain, Americans’ knowledge of Soviet crimes against humanity has been suppressed. Consequently, Americans have not fully understood the immense suffering communist regimes’ victims experienced. This is why Bitter Harvest is so important. In just 103 minutes, it professionally illustrates the Holodomor, one of 20th-century Europe’s central tragedies and one of the Soviet Union’s greatest crimes against humanity.

George Mendeluk’s Bitter Harvest is a drama set in Ukraine during the Holodomor,[1] Joseph Stalin’s artificially manufactured genocidal famine that killed millions of Ukrainians from 1932 to 1933. The film centers on a love story between Yuri (Max Irons) and Natalka (Samantha Barks), two young villagers whose bright future is thrown into chaos amid Stalin’s forced collectivization and reign of terror. Without spoiling the plot, I would like to share where Bitter Harvest excels.

As a work of historical fiction, Bitter Harvest takes a bold stance against Kremlin disinformation surrounding the Holodomor and clearly tells Stalin’s secret of how Soviet authorities deliberately and conscientiously waged genocide against Ukrainians. Bitter Harvest accurately conveys how genocide was intended to expedite a rebellious Ukraine’s acceptance of communist rule vis-à-vis agricultural collectivization and liquidation of the independent Ukrainian peasantry, abolition of Christianity in Ukraine, and squelching of Ukraine’s culture, national identity, and independence movement. To Bitter Harvest’s credit, these central themes are portrayed with little ambiguity. The film may not employ the most sophisticated methods, but critics should appreciate its straightforward approach, considering the ongoing decades-long denial of the Holodomor.

Bitter Harvest’s themes highlight significant historical aspects of the Holodomor particularly well, such as the Soviet war on Christianity. For example, when word first reaches Yuri’s village that Bolsheviks are coming, men hastily hide Christian relics for safekeeping. When the Bolsheviks arrive to plunder church property and enforce state-mandated atheism, they are frustrated to find the church preemptively stripped. The film’s primary antagonist, a ruthless Bolshevik commissar named Sergei, taunts the priest for his faith and beats him for refusing to reveal the valuables’ location. Because the priest refused to cooperate, Sergei executes him prominently in front of the church, which is thereafter repurposed into a state prison. Throughout the film’s remainder, Sergei terrorizes Natalka for a Christian icon, and when starvation becomes particularly acute, promises her life-saving food for its surrender. These themes clearly illustrate the Kremlin’s concerted effort to purge Christianity from Ukraine and the battle Christian Ukrainians fought to retain their faith.

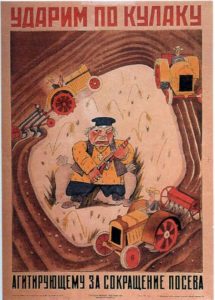

Another historical detail in Bitter Harvest is the Soviets’ Marxist class terror to destroy Ukraine’s independent peasantry. In the early 1930s, independent Ukrainian farmers who refused to surrender their private farming property to the state became targets. In February of 1930, the Joint State Political Directorate of the Soviet Union specified required measures for “liquidation of the kulaks as a class.” Branded as “kulaks” (literally Russian for “fist” and therefore by extension “the tight fisted”), Ukrainian farmers were demonized by Communist propaganda. Kulaks were portrayed as wealthy and greedy bourgeoisie whose subversive stubbornness to surrender their farmland prevented worker equality though socialism—the USSR’s grand purpose.

About the invention of the kulak, Yale professor Timothy Snyder writes, “In practice, the state decided who was a kulak and who was not, despite the fact that, ‘as a social class,’ the kulak (prosperous peasant) never really existed; the term was rather a Soviet classification that took on a political life of its own.”[2]

I was pleased Bitter Harvest depicted aspects of class terror against and political invention of the kulak. In one scene when Sergei enforces collectivization, he visits a farmer’s home and interrogates him about whether he owns the land. Sergei continues and asks if he privately owns livestock and, as a capitalist, hires fellow villagers as additional farmhands during harvest. Sergei then labels the farmer a kulak, to which the farmer responds that he is nothing more than a poor agrarian peasant. Based on the farmer’s plain appearance, work clothes, small house, and four young children, he and his family clearly work hard and do not enjoy any particular wealth. Sergei has no interest in his argument, and informs him that his property “now belongs to the state,” the state had already determined he was a kulak, and if he refuses to join the collective farming system he would either be sent to Siberia or shot. The farmer refuses and is eventually shot in front of his family.

In addition to bringing attention to significant historical details about the Holodomor, Bitter Harvest features a refreshing rebuke of moral relativism. While at the village church, Sergei symbolically says, “There is no God, no sin, no hell.” This is juxtaposed against Yuri’s last line in the film in which he states, “My Ukraine was a land where legends lived, and anything was possible. Before I grew up and learned that dragons were real and evil roamed the earth, I fell in love.” Yuri’s statement emphasizes that evil indeed exists and that it dominates the earth. Needless to say, a communist antagonist’s moral relativist denial of evil, contrasted against the protagonist’s Judeo-Christian understanding of evil is a rarity in the entertainment industry. I was pleased to see Mendeluk’s black and white portrayal of Stalin’s barbarity, the evil of communism, and the moral bankruptcy behind moral relativism.

While Bitter Harvest doesn’t win points for artistic creativity or high quality writing, it’s still a heartfelt and entertaining film, as well as a good general introduction to the Holodomor. Increased discussion of Soviet crimes against humanity in the entertainment industry should be welcomed, as film is a powerful medium capable of reaching a wide audience. Bitter Harvest’s true beauty is in its simplicity in that it teaches basic truths about communist crimes against humanity and helps historically contextualize Russia’s abusive relationship with Ukraine in a format palatable to the general public.

—

George Barros is a Washington-based analyst who concentrates on Ukraine and Russia. He previously worked as a foreign policy advisor for a former member of Congress who served on the Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats. You can find him on Twitter at @curiousgeorgie_

Feature Photo Credit: Still from the film Bitter Harvest.

[1] Etymology: The word “Holodomor” (Голодомор) is a compound Ukrainian word derived from the Ukrainian noun “holod” (голод), meaning hunger, and the verb “moryty” (морити), which, depending on context, can be interpreted as “to poison, drive to exhaustion, torment, or exterminate.” “Holodomor” can thus be translated and understood as “death by hunger” or “mass murder by starvation.”

[2] Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic, 2012. P. 78. Print.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024