Over the nearly four years running from December 1940 to September 1944, the inhabitants of the French village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the surrounding area collaborated together in a conspiracy of goodness. Risking everything, this modest-sized village had essentially doubled itself, giving sanctuary to some five thousand people—more than two-thirds of them Jewish—fleeing the Vichy authorities and Nazi regime.

The Chambonnais provided shelter, food, protection, and escape in their homes, in hotels and businesses, in the outbuildings of farms, in schools and other public buildings, and anywhere else they could fit the desperate and imperiled. The villagers also worked to forge identification and ration cards and to sometimes help ferry refugees into neutral Switzerland. The charity of the Chambonnais was indiscriminate. One child refugee said, “Nobody asked who was Jewish and who was not. Nobody asked where you were from. Nobody asked who your father was or if you could pay. They just accepted each of us.”

Why? As Huguenot Protestants, the Chambonnais’ own history might suggest at least a partial motive. As Frenchmen who came to embrace the new reformational teaching of John Calvin in the middle of the sixteenth century, the Huguenots quickly came into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church. It turned violent. While militant and iconoclastic extremists among the Huguenots made early advances, conquering a significant number of cities—and often brutalizing the Catholics there—they would eventually be subdued and increasingly persecuted until about the late eighteenth century. Violence, several massacres, and diaspora would drastically reduce their numbers in France, cutting their 1.8 million adherents in half within two hundred years. When the Chambonnais guides would escort endangered peoples the three hundred kilometers to the Swiss border, they would have been aware that their own brethren had long-ago made the same journey along the same roads and hidden byways.

This collective recollection of suffering as a religious minority bred within the people of Le Chambon a deep suspicion of authority. Few within the Huguenot community willingly cooperated with the Vichy government, and fewer still swore oaths of loyalty to Marshal Philippe Pétain, who served as the chief of state of Vichy France. Le Chambon rescue efforts were largely inspired and headed by the village pastor André Trocmé, his wife Magda, and his assistant Edouard Theis. Trocmé, a committed pacifist, launched a campaign of peaceful civil disobedience against Nazism. He gave sermons denouncing anti-Semitism, led protests against deportations, and blasted the cowardice of fellow Christians who stood idly by and did nothing to stop the horrors.

The story of Le Chambon is recounted in numerous places, but probably nowhere better than in a pair of books that are each—in their own and very different ways—inspired by the Chambonnais. Philosopher Phillip Hallie’s Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed is the definitive history. Hallie was thick in the midst of an in-depth study of the horrors of the Holocaust when he discovered and was overcome by the sheer goodness of Le Chambon’s story. It was a life-changing moment. Hallie describes having dug himself into a kind of hell, brimming over with bitter anger. When he unexpectantly found himself reading about Le Chambon’s church, he broke into tears of moral praise for the self-evident love displayed by Trocmé and his congregation. He caught, he said, a view of God. Hallie describes it:

It was this strenuous, this extraordinary obligation that … Trocmé expressed to the people in the big gray church. The love they preached was not simply adoration; nor was it simply a love of moral purity, of keeping one’s hands clean of evil. It was not a love of private ecstasy or a private retreat from evil. It was an active, dangerous love that brought help to those who needed it most.

After everything he had read about the worst things that human beings could do to one another, the goodness of Le Chambon was a disequilibrating shock. Hallie recalls how he went home that night, the memories of what he had read still working away at his subconscious. He could not get away from it.

When I lay on my back in bed with my eyes closed, I saw more clearly than ever the images that had made me weep. I saw the two clumsy khaki-colored buses of the Vichy French police pull into the village square. I saw the police captain facing the pastor of the village and warning him that if he did not give up the names of the Jews they had been sheltering in the village, he and his fellow pastor, as well as the families who had been caring for the Jews, would be arrested. I saw the pastor refuse to give up these people who had been strangers in his village, even at the risk of his own destruction.

Then I saw the only Jew the police could find, sitting in an otherwise empty bus. I saw a thirteen-year-old boy, the son of the pastor, pass a piece of his precious chocolate through the window to the prisoner, while twenty gendarmes who were guarding the lone prisoner watched. And then I saw the villagers passing their little gifts through the window until there were gifts all around him—most of them food in those hungry days during the German occupation of France.

Lying there in bed, I began to weep again. I thought, Why run away from what is excellent simply because it goes through you like a spear? Lying there, I knew … a certain region of my mind contained an awareness of men and women in bloody white coats [committing unspeakable atrocities to] six- or seven- or eight-year-old Jewish children… All of this I knew. But why not know joy? … Why must life be for me that vision of … children [hideously brutalized]? Something had happened, had happened for years in that mountain village. Why should I be afraid of it?

To the dismay of my wife, I left the bed unable to say a word, dressed, crossed the dark campus on a starless night, and read again those few pages on the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. And to my surprise, again the spear, again the tears, again the frantic, painful pleasure that spills into the mind when a deep, deep need is being satisfied, or when a deep wound is starting to heal.

Hallie’s book chronicles not just the history of Le Chambon but, in many ways, the history of a soul that is awakened to love.

A second book, quite different, is Albert Camus’ The Plague. While the novel is, on the surface, a morality tale about a North African town battling a deadly outbreak of bacillus, it is, at an allegorical level, a great proclamation against totalitarianism. It is quite possibly also an under-the-surface chronicle of the events in Le Chambon.

In January of 1943, Camus, battling with a recurrence of tuberculosis, heeded his doctor’s advice to relocate for a time from his home in Algiers to the French mountains. Camus spent about 15 months in Panelier, a hamlet about two miles from Le Chambon, where he wrote The Plague. Though this is disputed, there’s cause to believe Camus was already an active player in the French Resistance. While not a fighter, among much else he edited Combat, a daily that helped put the intellectual and spiritual steel in the spine of the resistance and that played a significant role in the post-war years. Hallie, who knew Camus slightly, was once told by a Chambonnais that Camus had met Trocmé on at least one occasion. In any case, in so small and intimate a region, it cannot be believed that Camus had no idea what was happening in Le Chambon.

The Plague is, at its most basic, a testimony of how we ought to act when people are at risk. One of the protagonists is Rieux, a medical doctor who leads the health teams in fighting the plague and caring for its victims. Rieux is, simply, a man who witnesses suffering and does what he must. As Camus has him say, “When you see the suffering it brings, you have to be mad, blind or a coward to resign yourself to the plague.”

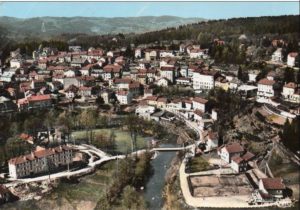

There are many reasons why the Chambonnais were successful in their rescue efforts. To be sure, geography played its role. Set atop the Vivarais Plateau in the Haute-Loire department of the hilly south-central region of Auvergne, the sheer remoteness of Le Chambon kept it off any primary radar. It helped, too, that elements of the French Resistance operated in the area, drawing attention away. While Trocmés and Theis were the principal catalysts of the rescue activity, they did have help: religious communities in nearby parishes, both Catholic and Protestant, joined forces with non-believers and others to aid the efforts. The solidarity of the local population sometimes extended to even the Vichy authorities, who would sometimes give warning to the Chambonnais when their village was about to be searched.

The rescue efforts sometimes failed. In 1943, German police raided a secondary school and arrested 18 students. Upon discovering five of them to be Jewish, they were deported to Auschwitz, where they died. Their teacher, Daniel Trocmé, the pastor’s cousin, was also arrested. He was deported to Majdanek Concentration Camp, where the SS murdered him. Roger Le Forestier, the town’s physician—who was instrumental in helping procure false documents—was arrested and executed in 1944. Resistance had its price.

This too resonates. The Plague ends with Dr. Rieux’s realization that, though the evil of the plague had been defeated, there would never be a final victory.

The plague bacillus never dies or vanishes entirely … it can remain dormant for dozens of years in furniture or clothing … it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers, and … perhaps the day will come when, for the instruction or misfortune of mankind, the plague will rouse its rats and send them to die in some well-contented city.

Against the plague—human evil—there can only ever be a never-ending fight against terror by those who, while not saints, are nevertheless committed to at least be healers. Within the fictional world of Camus—as with the very real world of Le Chambon 75 years ago—that was all that could be asked of good people willing to stand against the pestilence.

Marc LiVecche is the executive editor of Providence. From the fall of 2018 to the summer of 2020, he is the McDonald Visiting Scholar at the McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics, & Public Life at Christ Church, Oxford University.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024