Last week, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro in Boca Ratan, Florida addressed the Church of All Nations, which has a large ministry to Florida Brazilians and is a Pentecostal congregation part of the large and growing Assemblies of God denomination. The visit underlined the growing political power of Pentecostals and other evangelicals in Brazil and elsewhere in Latin America, where their numbers are surging.

It also illustrated a troubling penchant by many evangelicals for dangerous political impatience. Many Brazilian evangelicals evidently prefer military dictatorship over democracy and participated in the January 8 mob attack on government buildings in Brazil’s capital, based on their rejection of the most recent presidential election results.

At the Florida church, Pastor Mark Boykin introduced Bolsonaro as Brazil’s “newly elected” president, although Bolsonaro was defeated by two million votes in October, a result he and many of his supporters reject. Boykin, who is from Mississippi, prayed for America and Brazil to one day “learn to count when there’s an election.”

Many evangelicals support Bolsonaro because of his support for social conservatism but also evidently because they like his strongman political style. This penchant for traditional Latin caudillo politics does not bode well for Brazil’s democracy.

Last month rioters, many of them evangelicals, including pastors, refusing to accept the Brazilian presidential results, stormed the presidential palace, capital and supreme court buildings. They apparently hoped for a military coup to restore Bolsonaro, who never admitted his electoral defeat and left Brazil for Florida when his presidential term ended on December 31.

A group of invaders videoed in the Brazilian senate exclaimed: “Brazil belongs to Lord Jesus! The Senate is our church! The Senate is the church of the people of God!” Others prayed and sang hymns. One poll asserted that 64% of Brazilian evangelicals support a military coup in Brazil and nearly one-third supported the invasion of government buildings.

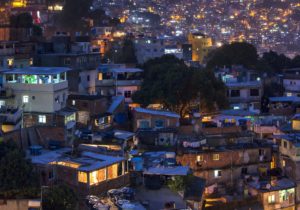

The 2010 census put Brazil’s population at over 20 percent evangelical, but a more recent estimate says Pentecostals are at 30 percent, possibly climbing towards an eventual majority. Unlike Catholicism or old-style Protestants, Pentecostals usually are not in centralized denominations with clear hierarchy and teachings. Their churches are often new, their congregants young, their pastors often charismatic and they depend on worship with signs and wonders. Pentecostalism often appeals to the very poor unreached by traditional churches and neglected by government social services. For them, Pentecostalism’s offer of direct encounters with the Holy Spirit is empowering. Pentecostals sometimes confidently believe themselves to be acting directly under God’s direction.

The consequent political implications might be egalitarian, democratizing and reforming. Or they could be impatient, polarizing, extremist and violent.

Evangelical/Pentecostal resurgence in Latin America can be likened to Calvinism’s post-Reformation ascendancy in parts of Europe, generating thrift, commerce, a larger middle class, and political resistance to arbitrary power by monarchs and aristocrats. But Calvinism also at times generated social strife, revolution, and civil war, as the “saints” demanded “godly” rule. Calvinists sometimes believed they were God’s instruments for establishing God’s reign on earth. The attack on Brazil’s chief government buildings by militants, some of whom are Pentecostal, evinces there’s some propensity for this perspective in Latin America.

With its dour view of human nature, Calvinism largely distrusted singular personalities and preferred corporate rule. But Pentecostalism often is built around charismatic pastors which can lead to support for charismatic politicians who claim that their connection with God, or at least with God’s people, overrides the lawful democratic process. Insistence on lawful democratic procedure can even be seen as secular and weak, while defiance and lawless action evince holy boldness.

Some commentators have tied Pentecostal involvement in the Brazil attacks to U.S. style “Christian nationalism.” That charge perhaps too nearly overlays American preoccupations onto Brazil. The January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol certainly included some Christian extremists who believed God ordained their lawlessness. But seemingly it was more spearheaded by non-Christians like the Proud Boys or esoteric spiritual hybrids like the QAnon Shaman. Yet the Florida church’s recently hosting Bolsonaro, and its pastor’s endorsing election conspiracy theories that led directly to political violence, evinces Brazilian evangelical and Pentecostal political proclivities are not confined to Brazil.

Brazil and Latin America for much of their history were dominated by colonialism followed by autarkies and dictatorships, often military. Many of the oppressive regimes were backed by, or at least relied on, collaboration with the Catholic Church. In the late 20th century, Latin Catholicism stood against dictatorship and supported transitions to democracy.

At the same time, Catholicism began to lose its religious and cultural monopoly in Latin America as evangelicalism, especially Pentecostalism, surged, especially in Brazil, Chile, and Central America. In the latter, evangelicals now outnumber Catholics. Understandably, this rising religious demographic expects political power. And inevitably, politicians appeal and pander to it.

Religious diversity and decentralization of religious authority can facilitate greater tolerance and democracy, with no single group able to dominate. But fast-rising new religious groups can be hubristic in their political and social expectations. If not firmly rooted in church tradition, Christians in these new groups can be especially susceptible to millenarianism, utopianism, and a false confidence confusing faith with political certainty. Pentecostalism’s strong focus on supernatural gifts and spiritual warfare can lead to political Manichaeism; believing politics is strictly a choice between clear good and evil, assuming opponents are demonic and conforming to conspiracy perspectives.

Christian wisdom understands the limits of politics and that even rule by the ostensibly godly can be profoundly ungodly. It also understands that strong faith is no substitute for or guarantee of political good judgment. Christian patience stresses that the fullness of God’s righteousness, justice and peace cannot be enacted through zealous human labor, including violence. And Christian mercy admits that even our earthly adversaries are created by God and still, at times, used by Him.

We can hope and pray that Brazilian evangelicals tempted by political impatience will listen to the Spirit’s constant call to forbearance and self-control.