As Israel’s war against Hamas drags on, the social and political fissures revealed in its wake have only become more salient. In the United States, antisemitism on the political left is becoming more apparent as the Democratic Party is stricken by infighting, while the racially-motivated murder of a Palestinian boy in the suburbs of Chicago by his landlord, a man he saw as a grandfather, speaks to the prevalence of violent anti-Arab sentiment. Hamas’s horrendous attacks on October 7th more than justify a strong military response, yet no one of goodwill can look at the mounting civilian losses in Gaza without heartbreak. Beyond the necessity of rooting out and destroying Hamas, there are no clear next steps in the process of putting a definitive end to this seemingly endless conflict.

It is beyond the scope of this article to go through the entire history of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Just War Theory, and left-wing anti-Zionism. However, examining two of America’s most famous Jesuits provides a framework for analyzing the conflict: Fr. Daniel Berrigan, and Fr. Robert Drinan. Separated by one year at Weston University, they became two of the most iconic opponents of the Vietnam War and the Nixon Administration; Berrigan through protests and other forms of direct action and Drinan as a member of Congress. Yet the two would significantly differ on Israel; while Drinan was an unconditional supporter of the Jewish state, Berrigan was resolutely anti-Zionist.

Drinan, one of two Catholic priests to ever serve in Congress, attributed his sympathy for Israel to the reports on the Holocaust from a Congressional Delegation. In the years before his election, he frequently wrote newspaper columns articulating Israel’s right to exist. Over his decade in the House of Representatives (1971-81), he easily won over 50% of the Jewish vote in each election, even when his opponent was Jewish. In 1973 he published an open letter to Pope Paul VI calling for the Vatican to recognize Israel, repeatedly criticizing Catholic leadership and the World Council of Churches for their “neutrality” during the Yom Kippur War. Drinan vigorously lobbied for military aid to Israel during the conflict despite his usual opposition to defense spending. He later went so far as to say the whole of humanity must be committed to the survival of Israel.

Berrigan would take a different position. In D.C. on October 19th, 1973 he spoke to the Association of Arab University Graduates in an address entitled “Responses to Settler Regimes.” Though critical of all sides, his focus was nevertheless squarely on Israel. Adopting the New Left’s fashionable rhetoric of “Settler Colonialism,” he accused Israel of deception, cruelty, militarism, and being the missionary vanguard of the “jackboot” oppressing minorities around the world. Recurring in the address are allusions to Israel as Nazi Germany, another common element in extreme anti-Zionist circles. Israel is charged with adopting the same logic as the Nazis against the Jews, but now against the Palestinians, with both Israeli and American Jews being seen as complicit in President Nixon’s “Asian Holocaust.”

When officially published in December 1973 it caused a firestorm among Berrigan’s allies, with some calling him a left-wing Father Coughlin. Condemnations came from Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant leaders. In Commentary, Robert Atler wrote a scathing rebuke, accusing Berrigan of messianism and errors. One example highlighted by Atler to showcase Berrigan’s anti-Israel bias was Berrigan’s focus on a military parade for Israel’s Independence Day; normally, the parade would be composed of children, but for the 25th anniversary a military theme was utilized to boost tourism. The decision was met with widespread condemnation in Israel, including from Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, not that Barrigan cared for such details.

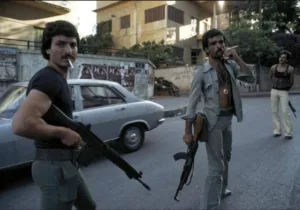

Rev. Donald S. Harrington, who had been selected to present the Gandhi Peace Award to Berrigan, refused to do so. While Promoting Enduring Peace, the awarding organization, decided that Berrigan should still receive his prize, Berrigan rescinded his acceptance, accusing his critics of regarding Israel with idolatry. A debate in 1974 with international relations scholar Hans Morgenthau went poorly for Berrigan, who walked back some of his statements and professed his admiration for Israel’s early achievements. Even so, Berrigan would maintain his overall critical stance, calling for the United States to reduce aid to Israel and hold direct talks with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1981.

Drinan articulated his pro-Israel stance in 1977 with Honor the Promise: America’s Commitment to Israel, which contained a foreword by Elie Wiesel saying Drinan would forever occupy a special place in Jewish history. At times dated and oversimplified, Drinan nevertheless makes his compelling case for Israel’s continued existence. Drinan saw a double standard applied to Palestine which, though receiving more aid over a longer period than West Germany, India, and Pakistan, nevertheless was unable to integrate its refugee population even as the aforementioned nations successfully did so. This failure led to refugee camps becoming breeding grounds for terrorists. Nor did world opinion care, Drinan argued, that unlike other “national liberation” movements, the PLO’s fundamental objective was the elimination of the state of Israel and not expelling an occupying power. The PLO was a terrorist organization with little support from Palestinians, being mostly the creation of Egyptian President Nasser for his Pan-Arab agenda. With a possible Palestinian state as a likely ally of the USSR, why should Israel allow the creation of a country that would place missiles and fighter jets 20 miles from their major cities? But threatening of all was the militant propaganda that permeated Palestinian society, extolling the need for violence to achieve freedom. This led Drinan, previously known as the anti-war Jesuit, to defend Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. While sympathetic to their plight, Drinan seemed to believe that the best option was for the Palestinians to integrate into Israeli and other Arab societies, a fate similar to that of the Baltic Germans who ultimately had to leave the Baltics, their home for centuries, to live among other Germans within the nation-state of Germany.

The divisions on the Catholic Left over Israel are not uniquely American but rather reflect cleavages the world over. Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini was beloved in the Jewish community for his support of Israel which was “second to none.” Shortly after his passing, he became the first Cardinal to have a forest named after him in the Jewish state. The beloved French priest Abbé Pierre, who rescued Jews during the Holocaust, initially supported Israel but later questioned its very existence, defended his friend and Holocaust denier Roger Garaudy (later walking this back), and accused the “international Zionist lobby” of attacking him and plotting for an empire that would stretch from “the Nile to the Euphrates.”

The divide speaks to a wider division in Christianity and the world about what it means to be Jewish. To Drinan, the Jews were God’s original chosen people. Despite a history of oppression, their continued survival was proof of God’s ongoing commitment to them. Supporting Israel fit as naturally to Drinan as his support for civil rights, prison reform, and anti-poverty measures. Jews, like prisoners and the poor, would always be close to God’s heart, something no true Christian could oppose. But for Berrigan, Jewishness is not membership in a religious or ethnic group, but a state of being. To be persecuted is to be a Jew. To be hated is to be a Jew. Thus, he was able to easily cast the Palestinians as the real Jews (a common feature of anti-Zionist propaganda) and Israel the new Babylonians.

Berrigan and Drinan represent the polar opposites of the Catholic left’s view of Israel, a contrast that elucidates the passions so many feel around the Arab-Israeli conflict. For Catholics, the issues at stake are not just moral or political but theological, concerning the Holy Land, the place of the Jews in the modern world, and love of one’s neighbor. Despite their differences, I suspect neither the Israel of Itamar Ben-Gvir, the notoriously anti-Arab Israeli politician, or the Palestine of Hamas would be their vision for the Holy Land. Let us hope neither scenario comes to pass.