This article about how U.S. foreign policy could build relations with Sunni tribes first appeared in Issue 2 (Winter 2016) of the print edition that came out last February. To read a PDF of the original version, click here. To subscribe and receive future issues, click here.

Introduction

The resurgence of Sunni extremists in both Syria and Iraq calls into question US strategy and policy approaches to countering Islamic violent extremism. In particular, the focus on building and supporting centralized and often non-inclusive governments in the region tends to marginalize and disenfranchise Sunni tribal elements of the population and contributes to their support of violent Salafist terrorists. Considering that the national borders and states of the Middle East are a legacy of the post-World War I dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and are artificial enclosures for the Sunni tribes present in Iraq, Jordan, and Syria (the Fertile Crescent), a better center of gravity for countering Islamic violent extremism is the Sunni tribes who are linked by cross-border ties of both kinship and religion. Not only do these tribes play an important power role in the Fertile Crescent, but given the potential divergence of their political and religious interests with those of extreme Salafists, there are opportunities to weaken non-state actors like the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) through political, military, and informational efforts with the Sunni tribes on a cross-border basis in the Fertile Crescent.

Successful engagement of these communities should occur along three lines of effort—the creation of more confederal mechanisms that give the tribes a true voice in local and national political matters; sustained military and political outreach directly to the Sunni tribes in the region to empower them in both dimensions, even if this sidesteps the existing national governments; and an intensive strategic communications campaign by Muslim partner nations of the United States to promote moderate strands of Sunni jurisprudence through education, the mosque network, and respected religious leaders. Ultimately, the United States needs to treat the different Muslim tribal societies on their own terms with honor and dignity in order to most effectively promote American objectives.[1] These steps may hold the key to reducing the wave of Islamic terrorism currently threatening the stability of the Fertile Crescent, but they require a step away from worshiping the full Westphalian concept of the state.

The Sunni Tribal Context

Most of the Sunni tribes in the Fertile Crescent originated from the Arabian Peninsula and maintain an enduring kinship among each other. Sunni tribes played a pivotal role in the creation of the Umayyad, Fatimid, and Ottoman Islamic empires, and they have always been key players in Middle Eastern regional stability. Their numbers show their potential influence, since the Sunni tribal society encompasses a considerable percentage of the population inhabiting the area stretching across Iraq, Jordan, and Syria. In Iraq, 95 percent of the population is Muslim, with 60-65 percent Shia and 32-37 percent Sunni.[2] Of the total Iraqi population, 75 percent are tribal members or have kinship to one.[3] In Jordan, 95 percent of the population is Sunni, rather traditional, and mostly tribal.[4] Lastly, for Syria, 68.7 percent of the population is Sunni Muslim, with 11.5 percent designated as Alawites.[5] Considering the percentages, a military, informational, and political outreach and engagement campaign to these tribes could offer a path to reducing the influence of ISIL and related threats.

In the colonial era, imperial powers tried to manipulate the tribes in an attempt to divide and rule the region.[6] Following the signing of the Sykes -Picot agreement between France and Britain in 1916 and the end of World War I, new national borders artificially separated the tribes that spanned the region from Syria, Iraq, and Jordan and limited direct interaction among them.[7] Nevertheless, blood kinship and common religious affiliation continued to shape and bind their ethnic identities and sustained cross-border ties that are still present.

Sunni tribes have always been considered important because of their population size, their territorial reach, and their significant influence.[8] The national governments of the region recognized the importance of the tribes early and attempted to control, subjugate, or gain their allegiance.[9] Yet, Sunni tribal society has demonstrated a remarkable flexibility in loyalty to states depending on their social and political interests throughout the years. Tribes and states form a dialectical symbiosis that fluctuates between mutual support or destruction.[10] History has shown that Sunni tribes usually resist manipulation from any central government, since it is in their nature to preserve their independence.[11] Hence, tribal support to any government has been fickle, with shifting loyalties depending on tribal interests. For instance, the military success of Ibn Saud could be credited to the Wahhabi-Bedouin tribal warriors known in the early 1920s as Al-Ikhwan, or “the brothers.’’ Years later though, these same tribal members attempted to topple the Saudi royal family.[12] Likewise, Sunni Bedouins in Jordan have routinely changed loyalty based upon power shifts, beginning with fealty to the Turks, then to the British, and finally to the Hashemite dynasty.[13]

Western strategists and policymakers should stop talking about a “clash of civilizations” and focus on the real problem: extreme tribalism. Recent events—the rise of ISIL, Sunni-Shiite warring in Iraq, the Taliban resurgence in Afghanistan—confirm that the West is not in a clash with Islam. Instead, Islam, which can be a civilizing force, has fallen under the sway of Islamists, who are a tribalizing force.[14] Thus, the best way to counter these extreme groups is to reinforce and support opposing tribes. There are three reasons to consider the tribal approach: economic, social, and political. Tribes are an immediate source of a skill base, and can be used quickly to improve the local economy and employment. Tribes provide a cohesive indigenous social structure; hence, a new organizational institution does not have to be built. Finally, building relationships with tribes shows cultural awareness, respect for the local populace, and stores political capital that can be used over the long term.[15] This political capital can also be used transnationally since the Fertile Crescent tribes are linked with each other and to their kinsmen in the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia. Successful tribal engagement in countering Sunni extremism should promote more autonomous political arrangements for the Sunni tribes, take and apply sustainable examples of tribal military cooperation from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and address other strands of Sunni religious jurisprudence and thought to diminish the influence of extremist Salafist ideologies among the Sunni tribal populations of the three Fertile Crescent countries.

Confederal Mechanisms

The current violence in the Fertile Crescent stems from the failure of modern states to deal effectively and peacefully with their tribal peripheries and religious minorities. The center is often marked by poor governance, corruption, and incompetence. As relations between the center and tribal periphery collapsed into violence, tribal societies broke down allowing the mutation of tribal and Islamic traditions into alien forms as represented by Al-Qaeda and ISIL. The only pragmatic and sustainable long term solution is to grant greater autonomy to the Sunni tribes with their full participation in the political process in all involved states, while ensuring governmental respect for their local culture and rights.[16] This requires a major political change for a dictatorial and Alawite-dominated Syrian government, a Shiite-dominated Iraqi central administration, and even considerations for Jordan in its relations with some of the Sunni tribes in its southern region. For the United States, it means backing away from a policy of promoting unified, centralized, and even democratically-elected regimes, and instead supporting confederal and tribally inclusive governmental arrangements for the countries in the Fertile Crescent. This concept is not new, and several noted authors have proposed different solutions aligned with this notion, stopping short of national partitions.

In fact, decentralization is hardly as radical as it may seem: the Iraqi Constitution, in fact, already provides for a federal structure and a procedure for provinces to combine into regional governments. For example, in Iraq, tribal Sunnis may have the most to gain from autonomy. The Sunni insurgency feeds on popular hostility to a Shiite-dominated Iraqi government, and while most Sunnis don’t support Al-Qaeda and its ISIL imitators, they often prefer them to Shiite Iraqi security forces, which are seen as complicit in the killings of Sunnis.[17] Once security and stability levels are normalized, the US must use its substantial economic and diplomatic powers to this end to encourage the affected central governments to establish an efficient, impartial, and honest administration working with tribal elders to maintain law and order and to provide them with tribal autonomy.[18] These US efforts should be transnational in nature to leverage the cross-border ties of the Sunni tribes in the three countries.

Sunni Tribal Military Empowerment

While the United States and its allies have recognized the military significance of the Sunni tribes in the current Fertile Crescent conflict against violent extremists, their utility must not be viewed through short-term, tactical lenses. The tribal system has been the means of governance in the Middle East for centuries.[19] As David Ronfeldt stated in Tribes First and Forever, “The tribe will never lose its significance or its attractiveness; it is not going away in the centuries ahead.” [20] Therefore, the US must deal with Sunni tribes directly as political entities.

With these powerful foundations, tribal partnerships can support the nation-state for both local governance and military efforts.[21] One need not look beyond Jordan’s tribal-based army to recognize the essential nature of tribal backing for the state. Many other examples can be cited on the other side of this equation.[22] There is great potential for tribes to contribute to the success of any national security strategy across the full spectrum of military operations. Additionally, tribal forces have exhibited success in providing functional capacity (intelligence and law enforcement) and acting as a force multiplier.[23] With this in mind, there is no doubt that Sunni Arab tribalism can have a substantial socio-cultural, political, and security impact on the Fertile Crescent region.[24] It just needs to be mobilized in the right direction.

To achieve security, tribal military cooperation is needed to deprive ISIL and its associated groups of their Sunni incubator in the Fertile Crescent. [25] Sunni tribal support for ISIL is not immutable, and the reasons for the current alignment are complex. ISIL may provide tribes with certain services and punish those who are not loyal to the group. But tribes that have aligned with ISIL have done so mainly because it is strategically beneficial in their conflict with the national governments in Baghdad or Damascus. The tribes are trying to position themselves to negotiate greater decentralization and the removal of Shia militias from their territories, and until that happens, they are likely to stay ambivalent on the issue of fighting ISIL.[26]

For the Iraq and Syria region, one oft-cited model for emulation is the Sunni Tribal Awakening “Project-Sahwa,” which was initiated in 2006 in Iraq and received the support of the United States in order to counter Al-Qaeda terrorism. By working with the Military Councils and the “Sons of Iraq” as part of the so-called Sunni Awakening, this counterterrorism strategy from 2007-2008 proved to be successful; however, it did not last for long—mainly due to lack of sustained US military engagement in Iraq. The same Sunni tribes who fought against Al-Qaeda in Iraq at that time are the ones who are supporting ISIL in its war against the governmental forces today. In Syria as well, Sunni tribalism has fueled the unrest against Assad forces across Syria since March 15, 2011. [27]

Mobilizing Iraqi and Syrian Sunni tribes against ISIL will not be an easy task, and it will require a far greater financial and manpower effort from the US government and its allies than they have thus far shown. But Washington was successful in the same terrain before, and its efforts could now be paired with surgical airstrikes against massed ISIL forces and, in the long term, potentially with combat advisors.[28] Nevertheless, the Obama administration will need to overcome its concern of undermining Iraqi and Syrian sovereignty, and provide aid and support directly to the Sunni tribes in both countries since tribal boundaries ignore the national borders. For Iraq, the current plan to create a tribally-based national guard seems to present a fundamental dilemma for the United States and the Baghdad governments: how to devolve security to the local level and empower communities to fight ISIL while avoiding the inadvertent encouragement of greater fragmentation in Iraq, the formalization of militia rule, and future military challenges to central authority. In truth though, the Baghdad government already controls considerably less than half of the country, and it will never regain any more control unless it can mobilize Sunni tribesman to fight ISIL.[29] Furthermore, the Kurds and Shiites already have their own separate forces, so the precedent is set for the creation of anti-ISIL Sunni militias. A similar, but more complex situation applies to Syria given the Assad regime’s endurance, but there the moderate Sunni tribes are critical to preventing Islamist dominance of future political outcomes. In both locations, the Sunni tribes are the center of gravity, and the US government must work with them directly and cross-border to develop an important military force for stability.

Sunni tribal society, Salafist-Jihadist ideology, and the other Sunni religious strands

Changing the mindset of the Sunni tribes is of equal importance to gaining their military and political support since the Sunni tribes in the Fertile Crescent have been hijacked by the extreme Salafist variant of Islam. The causes are varied and include: proselytizing by returning Jihadists from Afghanistan in the mid-to-late 1990s; the marginalization of the Sunni tribes, especially in Syria under the Baathist regime and in Iraq following the 2003 US invasion; and the desire for an Islamic Caliphate state, which will supposedly return the tribes to the age of the Rashidun caliphate, “the age of the successors of the prophet,” and enable the clans to regain their lost power and bring an end to their perceived subjugation and humiliation at the hands of secularist central governments, the West, and the Israelis.[30] The Sunni tribes that declared their loyalty to the terrorist organization ISIL in April 2013 demonstrated their belief in this latter vision.[31] All of these factors have created fertile terrain for the propagation of Salafist extremism.

In order to break the hold of Salafism on the Sunni tribes and to loosen its dominance of the current political-religious narrative, the Middle Eastern allies of the United States, should launch a strategic communications campaign conducted via local schools, mosques, and religious leaders promoting the Shafi’i and the Hanafi schools of Sunni jurisprudence as an alternative and moderate approach to Islam and in order to build a counter narrative against Salafism.

In Islam, there are four main Sunni strands of jurisprudence (Madhahib)—Hanafi, Shafi’i, Maliki, and Hanbali—each representing different methodologies for interpreting Islamic Sharia law. The four schools derive their guidance from the Quran and the Sunnah (what the Prophet did) as their main source for reference, and they follow “Ijma” (consensus of opinion), especially when situations reach an impasse and cannot find a clear response in either the Quran or the Sunnah.[32] The differences between the four schools lie in the judgments and jurisprudence from the imams and religious scholars who follow them and not in basic fundamentals of faith.[33] The most relevant strands for the Fertile Crescent are the Hanafi and Shafi’i. The Hanafi School of jurisprudence, comprising 31% of Sunni Muslims worldwide, is the largest of the four strands.[34] It is also considered to be the most liberal of the four schools, and it is found in parts of Syria, Jordan, and Iraq.[35] The Hanafi School was predominant in the Ottoman Empire and therefore became a prevailing school in the Middle East.[36] The Shafi’i School occupies the middle position between the Hanafi and Maliki schools in the spectrum of Islamic laws.[37] It prevails among 16% of Muslims globally.[38] In Syria, both the Shafi’i School and the Hanafi are represented.[39] Three-quarters of the Syrian population are Hanafi Sunnis.[40] In Iraq, the non -Kurdish Sunni population is primarily following the Hanafi School, and the Kurds belong to the Shafi’i School.[41] In neighboring Jordan, most of the tribal population is Sunni Shafi’is.[42]

The emphasis on these two most predominant and existing Sunni schools of jurisprudence “Madhahib” in the Fertile Crescent is essential to countering violent extremism. Knowing that most of the Muslim population in that area has followed the Shafi’i and the Hanafi Schools of law for decades, a strategy that promotes these two moderate Sunni strands as part of a strategic communications campaign makes sense. The differences between these two Sunni schools and extreme Salafism potentially hold the key to building a compelling counter narrative to violent Salafist teachings.

The chasm between Salafism and the Hanafi and Shafi’i Sunni strands is wide, and the extreme Salafist approach in general clashes with these traditional schools of jurisprudence. The Jihadi-Salafist school has fundamentalist beliefs, and its followers criticize the Sunni tradition and reject common laws. They believe that all actions and decisions in life must be based on direct evidence from the Quran and Sunnah and the example of the Companions Salaf, and they reject all common practices and laws not explicitly outlined in the Quran and Sunnah.[43] They also adopt a strict interpretation of Islamic laws, “Sharia,” and their understanding of the concept of “Tawhid” (the unity of God) goes beyond the literal understanding of most ordinary Muslims, hence the rejection of all man-made laws.[44] Their ideology is also focused on the purification and the reconstitution of the Muslim society, especially the restoration of the Caliphate state, and on the rejection of rapprochement with other religions.[45] Jihadi-Salafists reject the four separate traditional schools of jurisprudence, which to them are a key factor in dividing Muslims.[46]

In contrast, the Shafi’i and the Hanafi schools have more moderate norms than Salafism, and their adherents have a legalistic and casuistic vision of the “Sharia.” They accept the continuity between the founding texts of the Quran and Sunnah and rely on the daily life of the Prophet as a basic principle.[47] Moreover, whereas the Hanafi and the Shafi’i schools use “Ijtihad” (individual interpretation) and “Kalam” (mainstream Islamic theology) as references for their judgments, this is completely rejected by Salafism, which allows Jihadi Salafism the liberty to come up with more radical and destructive ideologies.[48] For example, the Salafist version of transnational Jihad justifies mandatory participation in regional or global terrorist operations, while the four schools reject this worldview.[49]

Since the foundations of religious moderation are already present in the region through the existence of the Hanafi and the Shafi’i schools of jurisprudence, a long-term counter terrorism strategy in the Fertile Crescent must foster these pre-existing Sunni schools among the tribal societies via religious education, while mobilizing imams, scholars, and other prominent figure to carry the messages to the tribal members. This effort is long term, and perhaps multi-generational, but it can begin the process to separate the Sunni tribes from the extreme Salafist ideology, and align them with other, more credible and authentic strands of Sunni jurisprudence.

Conclusion

The Sunni tribes in the Fertile Crescent, linked by kinship and religion, hold the key to subduing the ISIL threat and bringing stability to this critical geostrategic region. The political path to achieving their cooperation requires strong US and regional support for confederal arrangements that give the Sunni tribes a certain degree of autonomy under local political systems in order to reduce their inclination toward any radical Salafist ideology that would promote a transnational caliphate. Their military collaboration requires sustained effort from the US and its allies to arm, train, and equip Sunni tribal militias that can protect their people from ISIL, but also to prevent depredations by Shiite, Salafist Sunni, and Alawite forces. Finally, the promotion of the moderate Hanafi and Shafi’i schools of Sunni religious thought by the US—but more importantly by its Islamic allies—via education, religious scholars, and mosques should redirect the Sunni tribes away from Salafism to a more traditional, understood, and moderate path that remains true to Islam. Considering the relevance of the Sunni tribes to the Fertile Crescent, any plan against Islamic violent extremism in the region that does not account for their absolutely central role in a sustained and responsive manner is doomed to failure.

—

Kevin D. Stringer, Ph.D., is a Fellow at the Center for the Study of Civil-Military Operations at West Point and a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve.

Lama Jbarah is a Jordanian-American researcher of Middle Eastern affairs and has an M.A. in International Relations from Webster University.

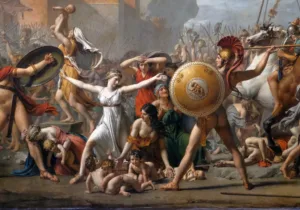

Photo Credit: Battle of Karbala, Abbas Al-Musavi, Brooklyn Museum.

[1] Akbar Ahmed. The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2013), 327.

[2] “Country Profile, Iraq,” Library of Congress, Federal Research Division (August 2006), at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Iraq.pdf, accessed September 15, 2014.

[3] Hussein D. Hassan. Iraq Tribal Structure, Social, and Political Activities (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2007).

[4] Werner Ende and Udo Steinbach. Islam in the World Today: A Handbook of Politics, Religion, Culture, and Society (Ithaca: London: Cornell University Press, 2010) 504, at http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2005/51602.htm, accessed December 30, 2014.

[5] Nikolaos Van Dam. The Struggle for Power in Syria Politics and Society Under Asad and the Ba’th Party (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 29.

[6] Michael W. S. Ryan. Decoding Al-Qaeda’s Strategy; the Deep Battle Against America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 188.

[7] Hassan Hassan, “Tribal Bonds Strengthen the Gulf’s Hand in a New Syria,” The National Opinion, at http://www.thenational.ae/thenationalconversation/comment/tribal-bonds-strengthen-the-gulfs-hand-in-a-new-syria, accessed September 14, 2014.

[8] Hugo McPherson, W. Duncan Wood, and Derek M. Robinson. Emerging Threats to Energy Security and Stability Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Emerging Threats to Energy Security and Stability (London: Springer, 2005), 261.

[9] Jhon Shoup,“Nomads in Jordan and Syria,” Cultural Survival 8.1 (Spring 1984), at http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/jordan/nomads-jordan-and-syria, accessed September 14, 2014.

[10] Philip S Khoury and Joseph Kostiner. Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990), 7.

[11] Michael W. S. Ryan, Decoding Al-Qaeda’s Strategy; the Deep Battle Against America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 188.

[12] Robert Lacey. Inside the Kingdom: Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia (New York: Viking, 2009), 17.

[13] Mudar Zahran, “Jordan is Palestine,” Middle East Quarterly 19:1 (Winter 2012), 7.

[14] David Ronfeldt. Tribes-The First and Forever Form (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2006), 75.

[15] Richard L. Taylor, “Tribal Alliances: Ways, Means, and Ends to Successful Strategy,” Strategic Studies Institute Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College, August 2005), 1.

[16] Akbar Ahmed. The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2013), 330-331, 335.

[17] See for example Peter W. Galbraith, “The Case for Dividing Iraq,” Time, November 5, 2006 at http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1555130,00.html, accessed December 30, 2014; Edward P. Joseph and Michael E. O’Hanlon. The Case for Soft Partition in Iraq, Analysis Paper Number 12 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, June 2007); and Joseph R. Biden and Leslie H. Gelb, “Unity Through Autonomy in Iraq,” The New York Times, May 1, 206, at http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/01/opinion/01biden.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all, accessed December 30, 2014.

[18] Akbar Ahmed. The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2013), 337.

[19] Jim Gant. One Tribe at a Time: A Strategy for Success in Afghanistan (Los Angeles, CA: Nine Sisters Imports, 2009).

[20] David Ronfeldt. Tribes-The First and Forever Form (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2006), 29.

[21] Richard L. Taylor, “Tribal Alliances: Ways, Means, and Ends to Successful Strategy,” Strategic Studies Institute Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College, August 2005), 9.

[22] Richard L. Taylor, “Tribal Alliances: Ways, Means, and Ends to Successful Strategy,” Strategic Studies Institute Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College, August 2005), 5.

[23] Richard L. Taylor, “Tribal Alliances: Ways, Means, and Ends to Successful Strategy,” Strategic Studies Institute Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy (Carlisle, PA: US Army War College, August 2005), 15.

[24] General (Ret.) Mohammed Al-Samarae, “Time for another ‘Sunni Awakening’ in Iraq and Syria Tribal Network and their Implication for Syria,” CICERO Magazine, 14 September 2014, at http://ciceromagazine.com/opinion/time-for-another-sunni-awakening-in-iraq, accessed September 15, 2014.

[25] General (Ret.) Mohammed Al-Samarae, “Time for another ‘Sunni Awakening’ in Iraq and Syria Tribal Network and their Implication for Syria,” CICERO Magazine, 14 September 2014, at http://ciceromagazine.com/opinion/time-for-another-sunni-awakening-in-iraq, accessed September 15, 2014.

[26] Frederic Wehrey and Ala’ Alrababa’h, “An Elusive Coutship: The Struggle for Iraq’s Sunni Tribes,” Syria in Crisis, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace at http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=57168, accessed December 30, 2014.

[27] General (Ret.) Mohammed Al-Samarae, “Time for another ‘Sunni Awakening’ in Iraq and Syria Tribal Network and their Implication for Syria,” CICERO Magazine, 14 September 2014, at http://ciceromagazine.com/opinion/time-for-another-sunni-awakening-in-iraq, accessed September 15, 2014.

[28] General (Ret.) Mohammed Al-Samarae, “Time for another ‘Sunni Awakening’ in Iraq and Syria Tribal Network and their Implication for Syria,” CICERO Magazine, 14 September 2014, at http://ciceromagazine.com/opinion/time-for-another-sunni-awakening-in-iraq, accessed September 15, 2014.

[29] Max Boot, “Abandoning the Free Syrian Army,” CommentaryMagazine.com, at http://www.commentarymagazine.com/author/max-boot/, accessed December 17, 2014.

[30] Laurent Bonnefoy, “Saudi Arabia and the Expansion of Salafism,” NOREF Policy Brief, (September 2013), 2, at http://caerusassociates.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/PRISM-Syria-Supplemental-Syrias-Salafist-Networks.pdf, accessed September 15, 2014, and Assaf Moghadam , “ Motives for Martyrdom Al-Qaida, Salafi, Jihad, and the Spread of Suicide Attacks,” International Security– MIT Press, 2009, at http://insct.syr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Moghadam-Assaf.2008.Motives-for-Martrydom.International-Security.pdf., accessed September 14, 2014.

[31] Roberto Marin-Guzman, “Arab Tribes, the Umayyad Dynasty, and the Abbasid Revolution,” The American Journal of Islamic Social Science: 21-4 (2010), and Michael W. S. Ryan. Decoding Al-Qaeda’s strategy: the Deep Battle Against America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 187.

[32] Samiul Hasan. The Muslim World in the 21st Century: Space, Power, and Human Development (New York: Springer, 2014 ), 29-30.

[33] Patrik J. Roelle. Islam’s Mandate: A Tribute to Jihad: The Mosque at Ground Zero (Authorhouse, 2010.), 233.

[34] “The Five School of Islamic Thought,” at http://www.al-islam.org/inquiries-about-shia-islam-sayyid-moustafa-al-qazwini/five-schools-islamic-thought, accessed October 15, 2014.

[35] Dana Zartner. Courts, Codes and Custom: Legal Tradition and State Policy Toward International Human Rights and Environmental Law (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014), 132.

[36] Coline Imber Ebuʼs-suʻud. The Islamic Legal Tradition (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 25.

[37] Dana Zartner. Courts, Codes and Custom: Legal Tradition and State Policy Toward International Human Rights and Environmental Law (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014), 132.

[38] Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad. Theory and Practice of Modern Islamic Finance: the Case Analysis from Australia (Boca Raton, Fla: Brown Walker Press, 2010), 79.

[39] “Syria Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments,” International Business Publications, Washington DC. 1(2013): 57.

[40] Elie Elhadj. The Islamic Shield: Arab Resistance to Democratic and Religious Reforms (Baton Rouge, FL: Brown Walker Press, 2006), 97.

[41] “Sunni Islam in Iraq,” The Global Security, at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/iraq/religion-sunni.htm, accessed December 31, 2014.

[42] Carole French. Jordan (Halfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, 2012), 31.

[43] Quintan Wiktorowicz ,“The New Global Threat,” Middle East Policy Council 1.4 ( Winter 2001): 3.

[44] Moghadam Assaf. The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 45.

[45] Oliver Roy. The Failure of Political Islam (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994), 33.

[46] Dana Zartner. Courts, Codes and Custom: Legal Tradition and State Policy Toward International Human Rights and Environmental Law (Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014), 132; Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad. Theory and Practice of Modern Islamic Finance: the Case Analysis from Australia (Boca Raton, Fla: Brown Walker Press, 2010), 79; “Syria Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments,” International Business Publications, Washington D.C.1(2013); Elie Elhadj. The Islamic Shield: Arab Resistance to Democratic and Religious Reforms (Baton Rouge, FL: Brown Walker Press, 2006), 97; “Sunni Islam in Iraq,” The Global Securit, 2006,at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/iraq/religion-sunni.htm, accessed December 31,2014; Carole French. Jordan (Halfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, 2012), 31; and Quintan Wiktorowicz,“The New Global Threat,”Middle East Policy Council 1. 4 (Winter 2001), 2-3.

[47] Oliver Roy. The Failure of Political Islam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 30-31.

[48] Christopher, Heffelfinger. Radical Islam in America Salafism’s Journey from Arabia to the West (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2011).

[49] Joas Wagemakers. A Quietist Jihadi: The Ideology and Influence of Abu Muhammad Al-Maqdisi (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.), 9, and Hassan Mneimneh “Jihadism,” Critical Threats, at http://www.criticalthreats.org/al-qaeda/basics/jihadism, accessed January 4, 2015.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024