For as long as anyone can remember, cookouts and fireworks have been the normal way for Americans to celebrate Independence Day, in the United States and around the world. Few if any Americans remember that such Fourth of July celebrations once occurred in a place where they are inconceivable today: Pyongyang, now the capital of North Korea. Almost exactly halfway between the signing of the Declaration of Independence and today, in 1896, Americans celebrated Independence Day in Pyongyang for the first time. How it occurred is important to remember at a time when tensions between the United States and North Korea have reached a new high, and the bizarre regime that rules Pyongyang for many seems impossible to understand.

Pyongyang in 1895 was a city living in a period of turmoil. Japanese and Chinese armies had fought a battle in Pyongyang in September 1894 during the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War. Koreans fought invaders and each other as guerrillas rose in 1894 against both the Japanese and the collapsing Korean monarchy. It was the start of an era of invasion and colonization by Japan and Korea’s loss of its independence, when many Koreans embraced Christianity and American ideals as the answers to the crisis engulfing their country. It was during this time that three American clergymen ventured north from Seoul to found a mission in Pyongyang.

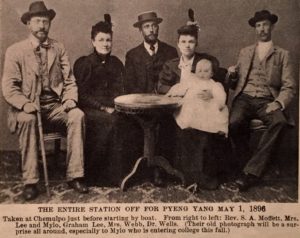

In May 1896, the Presbyterian mission in Pyongyang doubled in size and included women for the first time when the first American medical doctor there, J. Hunter Wells, and the wives of two mission members arrived. When July 4 came around, this small American community in Pyongyang was ready for a festive celebration on Independence Day. After a morning thunderstorm that made unnecessary a planned morning 13-gun salute, the half dozen Americans raised over two dozen American flags, sang patriotic songs, and ate, then capped off the day with a homemade fireworks display. As Dr. Wells later related in a letter to a newspaper in Portland, Oregon:

[T]he crowning event of the evening was our fireworks. We bought several pounds of Korean powder and made spit devils and other erratic articles and when the shades of night had settled down, our compound outside the city wall was made a bright spot in a weary land. We had half a hundred Koreans as spectators who bobbed up out of the earth, as it were, after our first figure was set off. After each piece was fired I let off with three cheers and horangai, including them in our good wishes for the Kingdom of Korea.

The mission rose from these modest beginnings to become the center of the most heavily Christian city in northeast Asia. The people of Pyongyang turned to Christianity with a zealousness and in numbers exceeding any other city in Korea. A wave of conversions called the Great Pyongyang Revival began in the city in 1907 and spread throughout Korea, and Christians numbered over 60,000 in the Pyongyang area by 1910. The success of the mission in Pyongyang led to it becoming the hub of Presbyterian activity throughout Asia, and the city received the nickname “the Jerusalem of the East.”

By the late 1930s, Pyongyang was a city of 300,000 that was one-sixth Christian, and the mission and its main institutions—Union Christian College, Union Christian Hospital, Presbyterian Theological Seminary—were the center of education, medicine, and religion in the city. The Second World War ended this era of American influence in Pyongyang, however. Most mission members left Korea in 1940 after a State Department warning of imminent war with Japan, and after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan deported those who remained and repatriated them to the United States in June-August 1942. When Soviet forces occupied the city in September 1945 to install a Communist regime in Pyongyang, they made a Red Army military headquarters out of the emptied mission compound, whose site continues to be under Russian occupation as the location of the Embassy of Russia in Pyongyang.

After 75 years without any official, media, or academic attention, the American presence in Pyongyang before 1942 has been completely forgotten by Americans, but North Korea’s ruling family has almost certainly not forgotten. Kim Il Sung was raised a Christian and sent to the boys’ school of Union Christian College by parents who were early Korean Presbyterians. The totalitarian rule and cult of personality that he created after 1945 have been violently anti-Christian and anti-American from their earliest years, no doubt rooted in the need to eradicate ideas and beliefs that many in North Korea had once embraced and might embrace again, which Kim Il Sung knew all too well. The contempt for the lives of Korean Christians and Americans that the North Korean regime has consistently displayed, recently in the cases of Kenneth Bae and Otto Warmbier, is unsurprising in this light. Americans would be well advised to remember this history after 75 years of forgetting.

—

Robert S. Kim is a lawyer who served as Deputy Treasury Attaché in Iraq in 2009-10.

Feature Photo Credit: Revs. William Swallen and Graham Lee (on horseback, with rifles) and mission founder Rev. Samuel Moffett at the start of the their trek from Seoul to Pyongyang in 1895. Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024