The hand of God is hard to discern, but what emanates from it is dazzling. The hand—actually just a few fingers—emerges in the middle of a stretched-out sheet of gray light. The sheet is surrounded by the symbols of the four Gospel writers—man, lion, ox, and eagle—and from its corners shoot out long bands of colored light, which look as if the squares of a multi-hued chessboard had been stretched out like taffy.

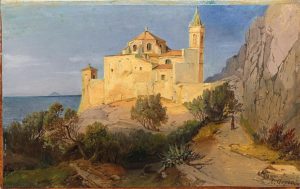

This vision (dubbed the “Apocalypse vault” by art historians) was painted by an unknown artist in the Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia—not the famous one in Istanbul, but a smaller one in Trabzon (medieval Trebizond) on the Black Sea coast of northeastern Turkey. The building and the paintings—the Apocalypse vault in the narthex and many more—were restored by a team of British archaeologists from 1957-1962. After the restoration, the building was opened to the public as a museum (I was there in 1993, leaning back to look up into the structure’s dome).

Turkey’s Islamist authorities put an end to all that. In December 2012, a Turkish court transferred control of the museum to the “General Directorate of Pious Foundations,” which set about converting the structure into a mosque; the job was completed in the summer of 2013. In the process, nearly all of the paintings of Hagia Sophia were covered up; the few that remain visible are susceptible to damage from the flash cameras of the now unsupervised tourists.

It’s of a piece with other disturbing developments in Turkey. Fortunately, there are also enlightened Turkish institutions dedicated to preserving the past rather than obliterating it. One such is ANAMED, the Koç University (Istanbul) Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, which has published Byzantium’s Other Empire: Trebizond, in English and Turkish editions. This beautifully illustrated book is a companion to a 2016 exhibition on the subject in Istanbul. It consists of a set of authoritative scholarly essays edited by Antony Eastmond of the University of London, the author of Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium, an exhaustive 2004 study of Trebizond’s Hagia Sophia.

It’s of a piece with other disturbing developments in Turkey. Fortunately, there are also enlightened Turkish institutions dedicated to preserving the past rather than obliterating it. One such is ANAMED, the Koç University (Istanbul) Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, which has published Byzantium’s Other Empire: Trebizond, in English and Turkish editions. This beautifully illustrated book is a companion to a 2016 exhibition on the subject in Istanbul. It consists of a set of authoritative scholarly essays edited by Antony Eastmond of the University of London, the author of Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium, an exhaustive 2004 study of Trebizond’s Hagia Sophia.

When we go from modern Trabzon to medieval Trebizond, we shift from dismal present to dreamlike past. From 1204 until 1461, the so-called “empire of Trebizond” was a remote and isolated eastern splinter of Byzantine civilization, strung out along the eastern Black Sea coast of Anatolia. It is part of late Byzantine history, when the empire was clearly declining, but tenacious in survival and still capable of marvelous things in art and culture.

At the dawn of the thirteenth century, the provinces in central Anatolia were already gone, in the hands of the Seljuk Turks and various Turkish tribes. In 1204 came a hammer-blow from the west, when the soldiers of the Fourth Crusade seized Constantinople. Once deprived of its capital, Byzantium fragmented. The most powerful exile-state was based in Nicaea in western Anatolia, to which many high officials of church and state had fled. The Nicaeans retook Constantinople in 1261, and eventually bound together a diminished empire.

But one piece was missing—the easternmost piece, which stayed autonomous. In 1204, Alexios and David Komnenos—brothers from an aristocratic family which had ruled Byzantium during the twelfth century—gained control of Trebizond, with support from neighboring Georgia. With the loss of Constantinople, they found themselves de facto independent. Within a decade, the Turks had overrun the central Black Sea coast of Anatolia, isolating Trebizond from the Byzantine lands to the west. David was captured in battle with the Nicaean Greeks; Alexios was left to become the first of a dynasty of (a wonderful word) “Trapuzentine” emperors. After 1261, the dynasty maintained diplomatic and marriage links with Constantinople, but otherwise went its own way, ruling a verdant coastal enclave and dealing with neighboring Turks, Georgians, and Armenians.

Eastmond’s chapter on Hagia Sophia in Byzantium’s Other Empire summarizes the discussion in his 2004 work. The church was erected by the Trapuzentine emperor Manuel I (reigned 1238-1263), outside the walls of Trebizond proper. Anyone given to fulminating about “cultural appropriation” may be concerned by certain features of the church’s exterior. Muqarnas niches were uncovered by the restoration team. Muqarnas is stalactite vaulting—carved stonework in a honeycomb-like design—and is a characteristic feature of Islamic architecture, including that of the Seljuk Turks. Here it appears on a Byzantine church. Nor, for that matter, was cultural influence limited to architectural features. Official titles at the court of the Trapuzentine emperors included some of Turkish origin.

The book’s highlight is the translation of the fourteenth-century chronicle of Michael Panaretos, a court official under the emperor Alexios III (reigned 1349-1390). Panaretos is no one’s idea of a great historian. His writing can be, as Eastmond stated in his earlier book, “laconic to the point of obtuseness.” Nevertheless, his chronicle is extremely important. The mainstream of late Byzantine history flows from Nicaea to Constantinople; Panaretos’ work stands apart, the sole surviving history from Trebizond itself. Panaretos describes the ferocious disputes within the Trapuzentine elite, as well as the emperors’ constantly shifting policies toward the neighboring Turkish tribes, whom they alternately fought and made marriage alliances with.

Trebizond was captured by the Ottomans in 1461, eight years after the fall of Constantinople. Yet a sizeable portion of the local population remained Christian, keeping folk memories of the Byzantine period alive. Even that ended in 1923, when the Greek Christians of the region were removed as part of the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Some of the old churches of the region had been converted into mosques during the Ottoman period; other monuments fell into decay. The result is summarized by the art historian Glenn Peers. “The empire of Trebizond is now a historical ghost, its culture largely effaced in its former territories and recoverable only through fragments.”

By turning the museum of Hagia Sophia into a mosque, Turkey’s Islamist authorities have made old Trebizond more spectral still. The sheer pettiness of this act is stunning. Was there a shortage of locations for Muslim worship in Trabzon when Hagia Sophia was a museum? No one who was there at the time, hearing the amplified sounds of the muezzin kick in one after another, would come away with such an impression. Almost the last remnant of the empire of Trebizond, of inestimable value, laboriously restored and pulled back from oblivion, has now been swatted down with contempt. It’s heartbreaking—and infuriating.

—

Richard Tada holds a PhD in History from the University of Washington.

Feature Photo Credit: Restored Hagia Sopia Church in Trabzon, Turkey in July 2010, two years before it was turned into a mosque. By İhsan Deniz Kılıçoğlu, via Wikimedia Commons.