An acme of my undergraduate years was to receive instruction and inspiration from Dr. Jeane Kirkpatrick. When I enrolled in her class at Georgetown University in 1994, it had been a decade since she served as President Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations, and 15 years since she wrote “Dictatorships and Double-Standards,” the essay which catapulted her to fame. Nevertheless, she continued to hold sway at the time, especially among Republicans yearning for a return to the Reagan era. I was not one of them, having led the campaign on campus supporting Democrat Bill Clinton, but I respected her intellect nonetheless.

Our seminar was devoted to French politics, in which Kirkpatrick was an expert. The wisdom I gleaned from her related less to France’s republic than to our own. Socialist François Mitterrand was the French president at the time, and despite his communist associations, she argued—perhaps surprisingly—that his time in power, following the Gaullists, had vindicated the Fifth Republic. A liberal democracy earns the name not with its first election, but with its second, or when the original incumbent party peacefully transfers power to an opposing one. Only when rulers “accept defeat when necessary,” she wrote, is the rule of law and separation of powers, fundamental to liberalism, truly tested. Modern France passed this test with Mitterrand’s election in 1980; the United States passed it with Jefferson’s election in 1800. This dynamic concept of democracy as a culture of governance conceived in liberal ideals but sustained through the realities of power politics stuck with me.

Kirkpatrick has since passed from the scene, but her influence lives on, as evidenced in Robert Kagan’s exhaustive essay “The Strongmen Strike Back,” the subject of Providence’s present debate. Kagan cites Kirkpatrick at the beginning, in the middle, and toward the end of his piece. Indeed, “The Strongmen Strike Back” can be seen as Kagan’s answer, 40 years hence, to Kirkpatrick’s “Dictatorships and Double-Standards.” And his response to her across the decades is quite critical. He argues that her interpretations of history are “fantasy,” her propositions “dubious,” her arguments “mistaken,” and her theories “wrong.”

The personal rivalry stalking Kagan’s essay is all the richer because both he and Kirkpatrick belong to the same band of partisan renegades who have repeatedly recast US foreign policy over the past half-century. Kirkpatrick became a socialist, then a Democrat, and finally a Republican as she sought the most effective outlet for her consistent anti-communism. In a reverse trajectory, Kagan began as a traditional Republican, converted to neo-conservatism, and eventually backed the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in a quest for liberalism’s most effective champion. They share a history of provocative and principled party defiance.

In her essay, Kirkpatrick sought to develop a “realistic program for dealing with non-democratic governments who are threatened by Soviet-sponsored subversion.” At the time of her writing, the USSR and USA were sparring over the developing nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, many of which despots ruled. Kirkpatrick argued that the Carter administration’s efforts “to impose liberalization and democratization on a government confronted with violent internal opposition not only failed, but actually assisted the coming to power” of communists. She instead urged support of ruling regimes resisting “revolutionary” and “totalitarian” Marxism, regardless of their political character. Although Kirkpatrick prioritized the containment of communism, she did not abandon the promotion of democracy. She argued that “traditional” autocracies “do sometimes evolve into democracies” through a gradual process of organic “contestation and participation” which the United States could foster diplomatically. Kirkpatrick’s was a Cold War reinterpretation of the classic “enemy of enemy is my friend” doctrine, with the corollary that our enemy’s enemies could become friendlier through friendly means.

Kagan, in contrast, argues that “liberal democracies had overestimated the challenge of communism” and “underestimated the challenge of traditional authoritarianism,” which he asserts has been liberalism’s true enemy since the Enlightenment. Modern authoritarians, particularly Russia’s Vladimir Putin, prey on liberalism’s alleged Achilles heel, namely its inability to replicate the sense of solidarity and security offered by the racial, ethnic, and religious communities it supplants. Despite denouncing “endless categorizations,” he draws another, not between democracy and autocracy, but between liberalism and illiberalism. Authoritarians inherently subscribe, by Kagan’s definition at least, to the latter, and armed with new information technologies, they are expanding their reach. Liberal democracies, beset by illiberal, authoritarian impulses from within and without, “need to start imagining” the alternative, and presumably rise in their own self-defense, although Kagan’s policy prescriptions remain vague.

Kagan’s essay lacks the conceptual clarity and analytical sophistication of Kirkpatrick’s. It relies on a reductionist worldview which he concedes is “binary,” pitting liberal against illiberal states in a Manichean deathmatch. Because illiberalism represents a value system, rather than a governance structure, it allows for little chance of political transformation. The emergence of competing power centers—such as opposition parties, private enterprises, unions, non-governmental organizations, the media, or the church—has little bearing in this theory if the reigning culture remains illiberal. By contrast, Kirkpatrick distinguishes “traditional” dictatorships, which tend to operate in realist, Machiavellian terms, from “revolutionary” ones, which tend toward totalitarianism and aggression. Where Kirkpatrick sees a sliding scale, with states capable of evolving, Kagan sees a litmus test, with scant prospect for dynamic change.

The limits of Kagan’s political imagination are perhaps most evident in his thinly-disguised hostility to organized religion, which he all but equates to totalitarianism. His self-serving history of Enlightenment liberalism mocks the “religious age” preceding it, belittling theological debates and bemoaning the mind control supposedly exercised by “spiritual rulers.” He denounces the nineteenth-century Concert of Europe, celebrated by realists such as Henry Kissinger, for defending “the authority of the church,” and he pointedly characterizes Russia’s and Hungary’s contemporary demagogues as exponents of “Christian culture” and “Christian values.” Kagan closes his essay with anti-religious imagery: “Liberalism is all that keeps us, and has ever kept us, from being burned at the stake for what we believe.”

Nevertheless, Kagan grounds the liberalism he celebrates in faith. The crux of the American experiment, he claims, lies in its protection of individuals’ God-given “natural rights,” as captured in the Declaration of Independence. He channels Alexander Hamilton in asserting that these rights were “written…by the hand of the divinity itself,” above “mortal power.” Thus conceived, the fledgling United States posed an ideological threat to the “privileged orders” of Europe, including “the church.” In another black-and-white distinction, Kagan depicts religion as inherently illiberal but true faith as potentially liberal.

The consequences of this contradiction are illuminated by another political renegade antecedent to both Kagan and Kirkpatrick—twentieth-century Protestant theologian and public intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr. At first a socialist sympathizer, Niebuhr eventually became an ardent critic of communism and founded the school of Christian realism. He argued that the genius of American democracy was not so much its enshrinement of natural rights but its establishment of an internal balance of power, both between the branches of government and between government and civil society. The proper “Christian attitude” toward government, one that “stressed human depravity,” necessitated this balancing act. During much of the history of Western civilization, the church served as a crucial counterweight to organized secular power. Kirkpatrick witnessed the church’s liberalizing power from her perch at the United Nations. During her tenure, Pope John Paul II rallied the faithful in his native Poland to challenge their atheist Soviet overlords. The fall of communism and restoration of liberalism in Eastern Europe is in no small measure due to the Catholic Church’s resistance, based on its faith-based defense of human dignity and human rights.

Despite the shortcomings of Kagan’s analysis, it bears more relevance than Kirkpatrick’s to the challenge we currently face. Her subject was the subversion of traditional autocracies by revolutionary communists; his is the subversion of liberal democracies by illiberal authoritarians. The danger Kagan identifies is indeed clear and present. Authoritarians worldwide appear not only resurgent but assertive in their opposition to liberal norms, aided by new information technologies and influencing tactics, and abetted by anti-liberal fifth columns within the United States unabashed in their embrace of foreign authoritarians. “These days, some American conservatives find themselves in sympathy with the world’s staunchest anti-American leaders, precisely because those leaders have raised the challenge to American liberalism,” Kagan writes. Strange, but true.

Such treachery from among his former partisans drives Kagan to despair, with little to offer in terms of a policy response. “If nothing else,” he writes, the United States should “reconsider the idea of supporting ‘friendly’ dictatorships,” a doctrine he attributes to “Kirkpatrick’s arguments.” But even Kirkpatrick would reconsider Kirkpatrick’s arguments 40 years later. She did not advocate support for “friendly dictatorships” in general, but only those facing the threat of communist subversion—a threat today mostly moot. And her support for traditional autocracies was conditioned by the understanding that they could potentially democratize.

But could the world’s liberal democracies, led by the United States, not pursue a more active and ambitious defense than simply distancing themselves from dictatorships? The means for accomplishing this might lie with the very information technologies that Kagan accurately describes as the modern authoritarian’s instruments of torture. And the vehicle for a forward defense of liberalism abroad currently exists as well—the National Endowment for Democracy, a private foundation established by President Reagan in 1983 “dedicated to the growth and strengthening of democratic institutions around the world.” President Trump has repeatedly urged Congress to slash funding for this bipartisan initiative, raising further questions about his commitment to democracy. If fully resourced and challenged to fully leverage the innovations of our digital age, the NED and similar initiatives could help reverse the momentum in the direction of liberal democracy.

To paraphrase Kirkpatrick, “liberal idealism need not be identical with masochism,” as it was in her day, nor with defeatism, as Kagan suggests. In confronting the world’s resurgent authoritarian powers, we dare not appease them, as the Trump administration and many of its Republican supporters seem intent upon doing. To do so invites their further interference in our own democratic system of governance, and would betray the liberal ideals upon which the United States was founded. We can’t join them, so we must beat them by seizing the new weapons in the war of ideas to encourage their liberalization—a strategy I have no doubt my professor of French politics at Georgetown a quarter century ago would have applauded.

Matt Gobush is a contributing editor to Providence and previously served on the staff of the National Security Council during the Clinton administration, the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, and the US Senate. He currently serves on the Standing Commission for World Mission of the Episcopal Church. Matt works in the private sector and lives in Virginia with his wife and five internationally adopted children.

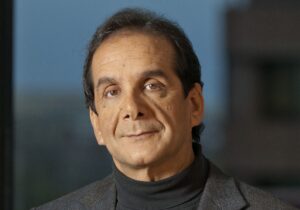

Photo Credit: US Ambassador to the United Nations Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, President of the Security Council for the month of March 1982, as she prepared to bring the Security Council meeting to order. UN Photo by Milton Grant, via Flickr.