There are many alive today too young to recall the majestic, providential events that unfolded 1981–91 when the Soviet Bloc peacefully shattered. It was one of the blessings of my life to have lived through those remarkable years, following them closely and tensely, first as a high school student and, by the end, a low-level intelligence analyst.

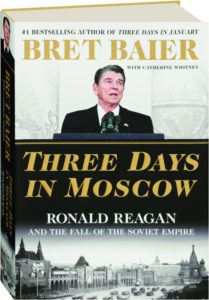

Convalescing from a recent injury, amid the coronavirus shutdown, I just finished Bret Baier’s succinctly captivating Three Days in Moscow: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of the Soviet Empire, which tells the incredible story. It brought back many memories, and at times even tears, as it recounted the final chapters of an over 40-year Cold War that could have concluded calamitously. Instead, its largely unexpected finale was peaceful, liberating and in many ways joyous. Not only was world war averted, which could have included nuclear apocalypse. But a totalitarian state that had murdered, jailed, and tortured many millions across 70 years was ended. Its collapse was, by the standards of fallen empires, relatively serene.

Baier tells this story mainly through the life of Ronald Reagan. Starting with his battles against Hollywood communists in the late 1940s trying to subvert the actors union that he headed, Reagan refined his Cold War mission across decades up until his 1980 presidential election at nearly age 70. He described it as “we win, they lose,” to often stunned interlocutors not accustomed to such bracing talk. But his methods were more sophisticated than critics admitted.

As President, Reagan would withhold vital technology and loans from the economically troubled Soviets, who had exploited detente to milk the West of desperately needed resources. He conducted a massive military buildup that opponents derided as dangerously provocative and wasteful. He channeled covert aid to peaceful resistance groups inside the Soviet Bloc, like Poland’s Solidarity trade union. He sent lethal aid to armed resistance groups on the periphery of the Soviet empire, especially in Afghanistan. But his perhaps most powerful weapon was the least expensive, was non-lethal, and yet still deeply controversial. Reagan rhetorically challenged the Soviet Union as a wicked but dying dinosaur that would not survive into the new information and technology age.

At his first White House press conference, which I watched with relish, Reagan warned the Soviets would resort to any depravity, “to lie, to cheat, to steal” in pursuit of communist hegemony. Later, he told the National Association of Evangelicals that the Soviets were an “evil empire.” He told the British parliament that the Soviet Union would end on “the ash heap of history.” In divided Berlin, he implored Mr. Gorbachev to “tear down this wall.”

The State Department and other bureaucrats tried to block these bold pronouncements, but Reagan unhesitatingly restored them to his speech drafts. Chattering elites globally deplored his bellicosity, which supposedly was returning the world to a dangerously chillier Cold War. The Soviets and their proxies reacted with surprise and anger. But imprisoned dissidents and other persons of conscience inside the Soviet Bloc heard this frank denunciation of their jailers with relief and joy.

Unlike some other conservative hardliners, Reagan was not angry, fearful, or militant. He didn’t envision the destruction of the Soviet Union but a peaceful transition in which liberated peoples on their own chose liberty. He appealed personally to three consecutive Soviet leaders, who rejected his overtures and died in short succession. Wisely, he avoided their funerals, instead awaiting a clear new leader who would merit a summit.

Mikhail Gorbachev, whom Reagan would first meet in Geneva, was his providential partner in ending the Cold War. He was perhaps the first Soviet leader who had not ascended to power through sheer brutality. And he was of a new generation who realized police state orthodox communism could not sustain the crumbling empire.

Reagan and Gorbachev established a genuine personal friendship even as geopolitical adversaries. The latter was intense while the former was relaxed and serene. This serenity in the older man was at first perplexing and intimidating but ultimately became reassuring to Gorbachev. The American adversary became a fatherly partner of whom Gorbachev, in the end, was seeking advice.

This path from confrontation to partnership was not smooth and included the showdown over US placement of new nuclear intermediate-range missiles in Europe, which the Soviets furiously resisted. Unsuccessful with bluster and threats, Gorbachev at their Iceland summit acceded to Reagan’s appeal for complete nuclear disarmament. But the caveat was ending Reagan’s cherished “Star Wars” missile defense initiative. Reagan said no, but the supposed failure of this summit would turn out to be a key step in the Soviet Union’s impending implosion. Unable to match America technologically or financially, Gorbachev later negotiated nuclear disarmament without disputing missile defense.

The denouement of Baier’s book is Reagan’s triumphant visit to Moscow, where he strolled Red Square with Gorbachev and declared the “evil empire” was no more. Before students at Moscow University, Reagan reached his rhetorical apex, pointing his mesmerized audience toward a future of human freedom and economic advance, while a huge disapproving bust of Lenin loomed over Reagan’s shoulder. The students cheered, and according to Reagan, Lenin wept.

After President George H.W. Bush’s election, Reagan met with Gorbachev and Bush in New York with the Statue of Liberty as their backdrop. Bush and others remained skeptical if quiet cold warriors. But one year later, the Berlin Wall fell. Two years later, the Soviet Union was no more. A near-century marred by unprecedented tyranny and bloodshed was concluded peacefully, unexpectedly, almost miraculously.

Reagan’s Cold War endgame resulted from many years of thoughtful consideration. Baier stresses Eisenhower’s influence on Reagan. During the 1960s as Reagan entered politics, Ike offered considerable counsel. Reagan later cited Ike as his modern presidential role model. Hardcore right-wingers often disdained Ike as moderate. But Reagan appreciated his measured wisdom from experience in war and peace.

Modern conservatism of course deeply shaped Reagan starting in middle age. But his early years were shaped by his low church optimistic Protestant piety, his small-town sense of community, his New Deal politics and veneration for FDR, and his devotion to trans-partisan American democratic ideals rooted in biblical anthropology.

For Reagan, each person was a creature of God and so meriting dignity, respect, and freedom. This promise was not just for Americans but all people, including the captive peoples of the Soviet Bloc. Gorbachev invited Reagan to Moscow to commemorate the 1,000th anniversary of Russian Christianity. The Soviet leader did not appreciate the full implication of this commemoration or of Reagan’s visit. Or maybe he did.

The story of ending the Cold War, and the Soviet Union, through the unfolding friendship of Reagan and Gorbachev, is beautifully told by Baier. This story, in its broad outline, should be treated like an epic poem or folk ballad, recited across future centuries, to remind fallen humanity when God intervened to save the world from calamity. Hopefully, His interventions are not over.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024