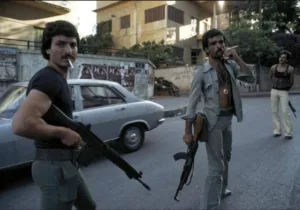

Ten years ago, the last rebellion of the Arab Spring broke out in Syria. In spite of the heavy price being exacted on those who dared to defy the despotism in Damascus, Syrians made haste to take their honored place in the great revolts sweeping Arab lands. After decades of living under a capricious and vicious tyranny, Syrians were determined to face down the author of their troubles. In response, the Baathist dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad ordered a ferocious crackdown against the country’s Sunni majority that ignited a savage civil war.

The robust movement for democracy and decency that sprung forth in March 2011 would not be easily thwarted and turned back. This uprising was animated by a sense that the submission and servitude long demanded by the Assad dynasty would no longer be Syrians’ fate. “This family thinks of themselves as gods, ruling Syria forever, while the rest of us are their slaves,” said one Syrian at the time. “I’m tired of being a slave.”

The conflict and desolation brought forth by the Syrian revolution constitute a stinging indictment, first and foremost of the Assad regime and its foreign patrons—most notably ground units supplied by the Islamic Republic of Iran and airpower provided by Putin’s Russia—but next of the mighty foreign powers that chose to abstain from the conflict and let Syria burn.

The butcher’s bill has never been easy to calculate with precision, but in the course of the conflict Assad’s forces have extinguished at least half a million Syrian lives. The regime ignited an insurgency with a distinctly Islamist character, and which eventually succumbed to the most pornographically violent jihadist outfits, including one proclaiming itself the Islamic State. Thirteen million people are displaced, half inside Syria and half unsettled elsewhere. In sum, the grisly coalition that laid Syria low has claimed a notorious place in what Winston Churchill called “the dark, lamentable catalog of human crime.”

Even at the distance of a decade, it is hard to account for both the barbarism of the belligerents as well as how dismally the Western democracies played their hand. It is also hard to escape the conclusion that Syria’s ordeal was only made possible by American abdication. The failure to end, or at least to ameliorate, the suffering in Syria, to say nothing of preventing the strategic consolidation of a post-American order in the Levant, has been astonishing to behold.

President Barack Obama entered office convinced that the United States was overextended in the world, and with plans to extricate America from the Middle East. In August 2011, with the Arab revolt in full swing, he nonetheless felt compelled to call on the Syrian dictator to “step aside.” He never seemed to consider what would happen, to the Syrian people or his own nation’s credibility, if Assad declined this invitation. Perhaps he believed that stern words alone would bring a cunning and ruthless despot to heel. In a post-imperial age, the president had no interest in willing the means by arming the Syrian opposition. In a gesture that conveyed the paucity of American strategic purpose, Obama belatedly approved CIA training of ten thousand rebel fighters—a small fraction of the Free Syrian Army—that never had any chance of altering the military balance on the ground.

The nadir of the Obama administration came in August 2012, when the president declared that if Assad used chemical weapons he would be deemed to have “crossed a red line.” Almost exactly one year later, Assad called that presidential bluff with horrifying consequences. On August 21, the Syrian military attacked rebel-controlled areas in the outskirts of Damascus with chemical weapons, killing nearly 1,500 civilians, including more than 400 children. Horrific video footage showing people with twisted bodies sprawled on hospital floors, some twitching and foaming at the mouth after being exposed to sarin gas. The US intelligence community had a “high confidence assessment” in both the nature of the attack and that it was ordered by the highest authority in Syria.

After a further round of feeble threats, Obama called off the planned airstrikes, to the dismay of his national security team and America’s principal allies. The administration then allowed the Kremlin to broker a deal under which the Assad regime divested itself of its chemical arsenal. Despite being lauded by Obama apparatchiks to this day, the deal was never fully implemented and Assad has since availed himself of chemical weapons on numerous occasions.

In an address to the nation on September 10, 2013, Obama declared that the United States was no longer the “world’s policeman.” In one fell swoop, America not merely betrayed its charge in Syria but relinquished its role in the world. A generation before, after Washington made no effort to arrest the genocidal bloodshed in Rwanda—a more peripheral theater than Syria from the standpoint of US interests—the American president felt sufficiently ashamed to admit to a grave lapse of judgment. Upon hearing Syria’s distress signals, Obama, the leader of the free world (to employ a quaint phrase seldom heard anymore), had all but announced the end of American leadership in the Fertile Crescent, and perhaps farther afield as well.

Ten years on, the rulers in Damascus sleep easily once again. Without incurring any great punishment from the outside world for their ghastly crimes, the crisis has left Assad and his henchmen emboldened. They have prosecuted the struggle with increased swagger since the distant superpower lost interest and averted its gaze from Syria’s agony. Always convinced they could ride out the storm sweeping the region, the barons of this barbaric regime were confirmed in their suspicion that they could also outwait their distracted foreign enemies. This wretched course of events has spelled untold misery for the revolution that once had the audacity to challenge the notion that citizens were the property of the state.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024